Pablo San Martín - Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation

Here you can read online Pablo San Martín - Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: University of Wales Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Wales Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

IBERIAN AND LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES

Western Sahara

Series Editors

Professor David George (Swansea University)

Professor Paul Garner (University of Leeds)

Editorial Board

David Frier (University of Leeds)

Richard Cleminson (University of Leeds)

Lisa Shaw (University of Liverpool)

Gareth Walters (Swansea University)

Rob Stone (Swansea University)

David Gies (University of Virginia)

Catherine Davies (University of Nottingham)

Pablo San Martn, 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff, CF10 4UP.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library CIP

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7083-22055 (hardback)

978-0-7083-23809 (paperback)

e-ISBN 978-1-78316-118-8

The right of Pablo San Martn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77, 78 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A Mara, por todo

Over recent decades the traditional languages and literatures model in Spanish departments in universities in the United Kingdom has been superseded by a contextual, interdisciplinary and area studies approach to the study of the culture, history, society and politics of the Hispanic and Lusophone worlds categories that extend far beyond the confines of the Iberian Peninsula, not only in Latin America but also to Spanish-speaking and Lusophone Africa.

In response to these dynamic trends in research priorities and curriculum development, this series is designed to present both disciplinary and interdisciplinary research within the general field of Iberian and Latin American Studies, particularly studies that explore all aspects of Cultural Production (inter alia literature, film, music, dance, sport) in Spanish, Portuguese, Basque, Catalan, Galician and indigenous languages of Latin America. The series also aims to publish research in the History and Politics of the Hispanic and Lusophone worlds, at the level of both the region and the nation-state, as well as on Cultural Studies that explore the shifting terrains of gender, sexual, racial and postcolonial identities in those same regions.

This book would never have been possible without the contributions, help and encouragement of many people. First, I wish to thank all the Saharawis who trusted me, opened their houses and jaimas and shared their stories of lack and desire with me. Thanks to all the Frente Polisario and Saharawi Republic (SADR) officials and diplomats for their invaluable assistance and to the countless refugee-citizens who shared with me their thoughts and concerns in the refugee camps of Tindouf. There, my friends and hosts Malainin Lakhal, in Rabuni, and Mulayahmed Abderrahman and his family, in Smara, deserve a special word of gratitude. The determination, strength and hope in the future of Tutu, Mulayahmeds little sister, was a lighthouse in an ocean of uncertainty. Thanks also to all my academic colleagues, whose comments, suggestions and ideas were indispensable to the writing of this work. Joanna Allans exhaustive readings and constructive comments on the drafts and final manuscript were much more helpful than she thinks. I have also benefited from the constructive comments of the external evaluators of this work. The process of nation-building explored in this book, as one anonymous reader of the final manuscript rightly points out, needs also to take into account the key role of the Saharawi diaspora in Mauritania and the relations between the Saharawis from the territories under Moroccan occupation and the refugee camps. Both issues deserve a more detailed attention than I can devote to them in this work. But I take note and accept the challenge for the future. This book is not a closed work but just a point of departure that, far from attempting to produce a final and closed panorama, aims at suggesting new lines of enquiry into the Saharawi story. Finally, I would like to thank all the institutions and funding bodies that made this book possible; the pilot fieldwork of this venture was carried out thanks to a small grant from the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, further fieldwork was funded by the British Academy, and the main stages of fieldwork, analysis and writing were only possible thanks to one year of sabbatical leave co-funded by the University of Leeds and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

All translations from Spanish are the authors unless otherwise stated.

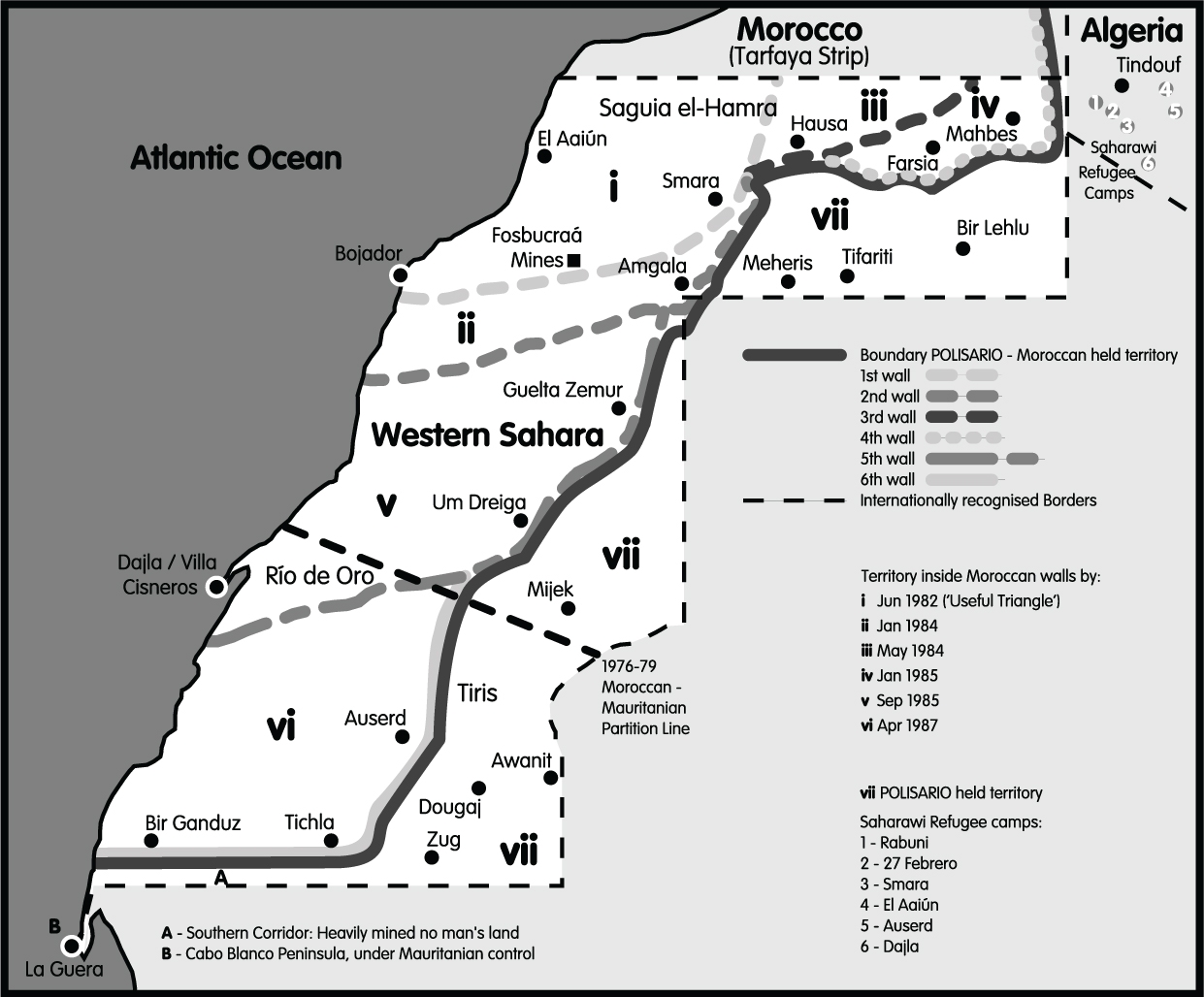

Figure 1: Western Sahara map

Introduction

My first image of the Western Sahara dates back to the early 1980s, when I was only a child. I was watching TV, the news, and I remember the presenter saying something about a war in a former Spanish territory, which looked very different from the exuberantly green and perpetually wet northern Iberian valleys of my childhood. But what really captured my attention were the images of guerrilla fighters with yellowish turbans, waving their Kalashnikovs and departing defiantly for the battlefield, crowded in the back of old open Land Rovers. I also recall Land Rovers reconverted into sorts of artisan assault vehicles, with machine guns fixed to their tops. Those images were, at least as I evoke them now, whitish and blurred, probably because of the collusion of the sirocco of those distant wide white lands of the greatest desert on earth and the black-and-white TV of my sitting room.

Whitish and blurred also describes some of the last and most powerful images that Liman can evoke from his homeland. It was the end of 1975, when, with his family, he had to flee the city of El Aain, capital of the then Spanish Sahara, to seek refuge in the desert. Spain, with dictator General Franco moribund in hospital, had hastily abandoned its colony without organizing the self-determination referendum that the United Nations (UN) had been demanding for over a decade. Taking advantage of Spains weakness, Morocco from the north and Mauritania from the south sent their armies to occupy a deserted territory inhabited by fewer than a hundred thousand Saharawis, but with immense natural resources. The UN officially opposed the occupation but did nothing to prevent it and the still-young Saharawi liberation movement, the Frente por la Liberacin de Saguia el-Hamra y Ro de Oro (Frente Polisario), which had been fighting against Spanish colonialism since 1973, was unable to stop their much more powerful expansionist neighbours. That the native Saharawis overwhelmingly supported the independence of the territory was palpable, as a UNs visiting mission had just confirmed. The Moroccan and Mauritanian troops were not precisely welcomed as liberators from European colonialism but, on the contrary, they encountered unexpectedly stiff resistance. For the new occupying powers virtually every Saharawi immediately became suspected of being a secessionist and within a few months, many hundreds of Saharawis had been killed or had disappeared and approximately half of the total population had been displaced. It all happened under the passive and indifferent gaze of the international community.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation»

Look at similar books to Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.