Mixing confessional narrative, literary analysis and history a neat, accessible work that, for westerners drawn to the vast reaches of this desert, asks all the right questions New Statesman

Not so much a travelogue as a pilgrimage, in which colonial history illuminates literary critique, which in turn sheds light on autobiographical confession Independent on Sunday

A powerful mix of travelogue and the history of French colonialism in North Africa. This is writing with a conscience that shows the enormous and provocative possibilities of the travel book Sunday Times

Europes long, often murderous history of racism towards Africa is chillingly summarized in this dazzling book which pursues Hannah Arendts view that the totalitarianism and butchery of Hitler and Stalin were both fathered by the terrible massacres and wild murdering of European imperialists Tribune

All is included in transformation. You too are subordinate to change, even destruction. So is the entire universe.

The journey is a door through which one goes out of the known reality and steps into another, unexplored reality, resembling a dream.

1

A large muddy stone is lying in the washbasin of my hotel room.

Carefully, I scrape off the mud and rinse it. The water coming out of the tap is black.

After I have washed the stone clean, it is as pink as the morning sky. It is pink granite and made of two rounded segments resembling the halves of a brain.

Yes, now I can see it it is my own brain which has arrived before me.

It is so heavy I can hardly lift it out of the washbasin.

2

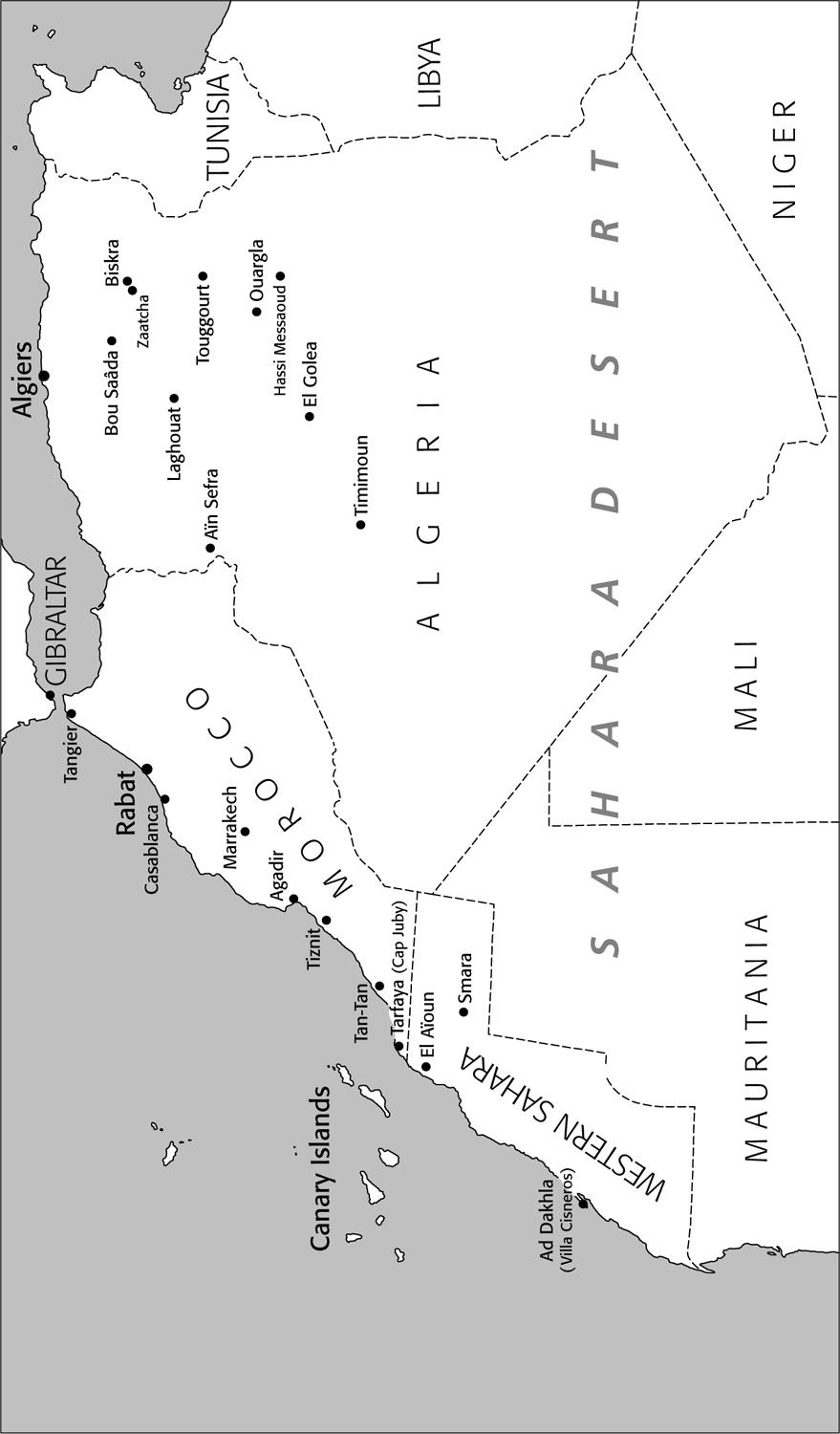

I am woken from my dream by the usual charter-flight applause, filled with profound relief that the plane has miraculously landed in one piece at the right airport: Agadir.

Bus to the Hotel Almohades. I rent a room for the night and a car for a month.

I am not drawn to the pool, but to the desert. As a child I read about fire-eaters and well-divers, about sandstorms and desert lakes. I planned a great journey in the Sahara. Now I am here.

I am alone. I have just parted from my volumes of Dostoevsky; with all my notes in them. I have parted from the woman who was once my beloved. I have parted from thirty-three years of my life.

This has one advantage the period of time before those thirty-three years has suddenly closed in on me.

As long as I remained in my childhood home, I could remember nothing of my childhood. It seemed to have been erased. Nothing but a bunch of anecdotes, no genuine memories.

Nor could I dream.

Now that I have moved, fragments of my childhood often come into my mind. And when I began to train with weights as I did when I was small, then I also began to dream.

Memories and dreams do not allow themselves to be forced. The very intention locks the door you want to open. You can only reach your goal by back ways and sidetracks.

One way I have tried to approach childhood several times is to do now what I so fervently longed to be allowed to do then. Even if it seems childish and unmotivated, sometimes I try what in the impotence of my smallness I dreamt of doing.

3

Its like diving into black water, says Antoine de Saint-Exupry about a night-landing in the Sahara.

When the mail planes in his novels landed for a stopover in Agadir, the pilots had four hours before they had to go on again. I remember that as if I had read it yesterday. They went on to the town and had dinner, their bodies still singing with the vibrations of the plane.

I eat prawns au gratin at the Water Garden restaurant opposite the hotel and drink a toast to the mail plane pilots in Oulmez fizzy mineral water. Will I find that there, down south, where it really will be needed?

I am not really worried about not finding any there, but just long for it to be necessary.

At about ten in the evening on October 30, it is a little cold around the shoulders to sit outside after dinner. I go to bed early. I lie there, drawing my soul together in the no-mans-land on the borders of sleep. Then the dream interrupted on the plane comes back.

Once again I am washing that stone in black water. Bats whistle around me in the dark of the cave, the breeze from their wings waking others asleep, hanging in the roof with their heads down. Heads? The whole cave is a head, an empty skull full of a whistling darkness, in which I stand with the pink stone in my arms.

4

The Stravinsky-chatter of sparrows in the bush, the sky blue with light clouds. Early in the morning, I leave the monkey mountain of humanity around the hotel pool, get into my little Renault and drive slowly south.

At first the hollows are still green and glisten with moisture. The fig-cactus is just bearing fruit and bunches of ripe dates hang heavy as udders below the tops of the date palms yellow, brown, dark red and ready to burst with the sweetness of dates.

Moroccos favourite colour is shocking pink. Instead of the white corners that we have on our red-painted houses, the houses here have reverse-stepped gables, highest in the corners and sinking towards the middle.

But soon the houses become fewer, the ground dryer. The greenery thins out until it looks like the sparse, tender green grass which grew in the sand of our Christmas crib when I was a child.

And as the desert opens up around me, as the sandy colours take over with their million monotonous variations, as the light becomes so intense that it hides shapes, extinguishes colours and flattens out levels then my whole body hums with happiness and I feel, This is my landscape! This was where I wanted to be!

I stop the car, get out and listen.

A cricket, dark as a splinter of stone, chirps shrilly. The wind whistles in the six telephone wires, a thin, metallic note I havent heard since childhood.

And then silence, which is even rarer.

Far away over there, the nomads dark goat-hair tent trembles in the midday heat. Their women and children come walking in the shadow of their burdens.

5

In Tiznit, some of them have camped north of the town wall. They come from the occupied areas in the south to sell their jewellery.

They are not veiled. They have fearless children and fearless eyes. One of them is called Fatima. She has flames painted in henna on her heels, licking her foot from below.

Calmly she spreads a blue cotton cloth out on the ground. Then she starts removing objects from a little chest.

I remember Agadirs shops and their over-decorated leather goods, their rattling metal tray-tables, their thick loose mats in clashing colours the way smoking-room orientalism has characterized the image of Morocco, perhaps the whole of North Africa.

Fatimas jewellery belongs to another, Saharan, tradition. Eagerly, I ask how much they are. She does not answer.

This isnt the bazaar, she admonishes me in Spanish.

I have to wait calmly as the ritual continues. Ornament after ornament is brought out and explained. The three tents on the lid of the box are the three tribes in Sahel. This bracelet shows drought and the rains.