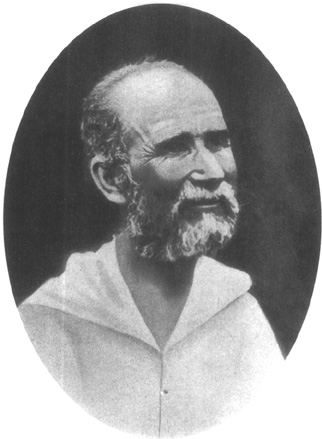

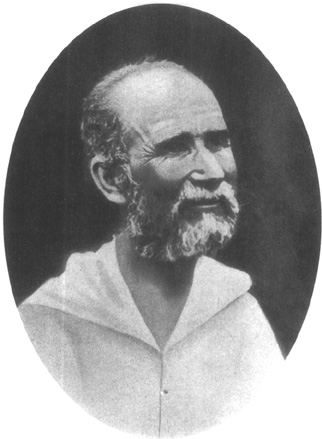

Foucauld in 1916.

Laperrine at the start of his career.

THE SWORD AND THE CROSS

Also by Fergus Fleming

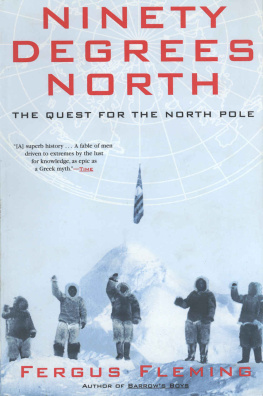

Barrows Boys

Killing Dragons The Conquest of the Alps

Ninety Degrees North The Quest for the North Pole

THE SWORD AND THE CROSS

TWO MEN AND AN EMPIRE OF SAND

Fergus Fleming

Copyright 2003 by Fergus Fleming

The two photographs reproduced in the front matter are copyright Royal Geographical Society.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in 2003 in Great Britain by

Granta Books, London, England

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

FIRST GROVE PRESS PAPERBACK EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fleming, Fergus, 1959

The sword and the cross / Fergus Fleming.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9752-8

1. SaharaDescription and travel. 2. Foucauld, Charles de, 18581916. 3. Laperrine, Henri, 18601920. I. Title.

DT333.F58 2003

966.023092dc21 2003049071

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

When France invaded Algeria in 1830 she didnt particularly want to create a colony; events just took their course. In similar fashion, this book was never meant to be a biography or a chronicle of French imperialism in North Africa; yet it seems to have become a bit of both. If it succeeds on either level then it does so by accident. Essentially, this is a tale of two extraordinary men who lived in an extraordinary place during an extraordinary time. It is their story, rather than their history, that I have tried to tell.

The main protagonist, Charles de Foucauld, aristocratic rou turned hermit, is a well-known figure in France, where many volumes have been published on his life. Here, in Britain, he has been virtually ignored save for a flurry of post-war hagiographies. (Before the Second World War our interest was so minimal that one biographer, Sonia Howe, could only find a publisher by writing in French.) Most authors have taken the angle that he was either a saint or the nearest thing to one. Certainly he has influenced many people. T. S. Eliot, for example, lectured on him during his prolonged conversion to Catholicism; and Foucauldesque images of the desert can be found in many of his poems. Tens of thousands of followers from the Thirties to the present day have hailed his life as a standard for theirs. (At present there are some 11,000 Little Brothers and Sisters of Jesus worldwide.) Whether he really was a saint, or whether he was just a disturbed fanatic or, indeed, whether the two are mutually exclusive are questions that fall outside the scope of this book.

Henri Laperrine is a more elusive character. To my knowledge, nothing has been written about him in English. He survives only in a few French biographies, the most recent of which dates back to 1940. He was not a great man, nor even a very famous one: nobody really knew about him until his death; and although he has since been immortalised on stamps and in the names of streets and schools, nobody really remembers him today. There are few photographs of him in action here an indistinct outline on a camel; there a kepied figure pausing by a doorway within a mud fort. He did not care for fame. Yet as the creator of the Camel Corps he played an important role in the conquest of the Sahara and seems, in his own way, to have been as complex as his monkish friend. His (universally gushing) biographers praise his reticence and his compassion; they remember the cheery twinkle in his eye. Reticent and compassionate he may have been, but according to one contemporary his smile also contained a glint of malice. His record shows him to have been a pragmatic man, violent and scheming though by all accounts great campfire company who went about his business without spiritual angst. He was a soldiers soldier, just as Foucauld was a Catholics Catholic.

Laperrine wrote little and what he did seems mostly to have been destroyed, leaving only a few letters and press articles. So shadowy has he become that accounts differ even as to his appearance. One author describes him as small, scruffy and squeaky-voiced, another as tall, impeccably dressed and strident. From photographs and contemporary descriptions he seems to have been an amalgam of the two, and this is how I have portrayed him. Foucauld, on the other hand, is disorientatingly well-documented. He wrote with fearful energy and his every utterance has been preserved. Whenever possible he posted at least three letters per week sometimes per day, and sometimes in code to friends, relatives and anyone he could think of. In the fifteen years before his death he wrote more than 700 letters to his cousin Marie de Bondy, another 700 to her husband Oliver de Bondy and some 6,000 more to scores of others. His correspondence with Bishop Gurin of the White Fathers, alone fills a book over 1,000 pages long. In addition he left more than 12,000 pages of assorted writings. Thanks to various French publishers predominantly Nouvelle Cit most of the material is now available in printed form.

Of secondary sources, Douglas Porchs The Conquest of the Sahara (1985) stands out not only for its wit but for the quality of its research. It is the bible for anyone interested in the subject. I have drawn on it heavily, both for quotes and for episodes that have little to do with Foucauld or Laperrine such as the horrors of the Central African Mission but which help place their careers in context. I have also relied on a medley of Foucauld biographers. Ren Bazin was the first of them. He knew Foucauld and wrote a definitive study five years after his subjects death. Most subsequent authors have to a greater or lesser extent relied on Bazins material, the main difference being the manner in which they have interpreted it. Anne Fremantles Desert Calling and Jean-Jacques Antiers Charles de Foucauld are not only well-written but offer the liveliest translations so I have preferred them, in places, over Bazins slightly dated version. On the subject of translations, quotes from secondary sources have been verified wherever possible against the original. The notes at the back should reveal whether a particular passage has been translated by me or by someone else. In general, if it reads well then its someone elses; if its a dogs dinner then its mine.

I would like to thank my agent Gillon Aitken; Sajidah Ahmad; my editor Neil Belton who has, as always, shown impeccable attention to the manuscript; Michael Graham-Stewart; Patrick Herring; Edward Hulton; David Macey for scrutinising the text for errors; Douglas Porch for pointing me in the right directions; Eugene Rae; Jane Robertson; Barnaby Rogerson; Lynne Thornton; Janet Turner and Joanna Wright. I would like further to thank the Bibliothque Nationale; the British Library; the State Historical Society of North Dakota; the Kensington and Chelsea Library; the London Library; the Royal Geographical Society and the School of Oriental and African Studies. Also, Claudia Broadhead, Sam Lebus and Matilda Simpson. Finally, thanks to Liz, Romar and Patrick for absolutely everything. This book is dedicated to my mother and my brother George, both of whom died during its preparation. I would like also to commemorate my aunt and godmother, Tish, who did likewise.

Next page