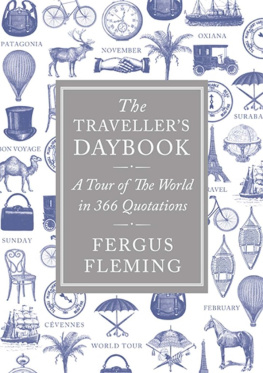

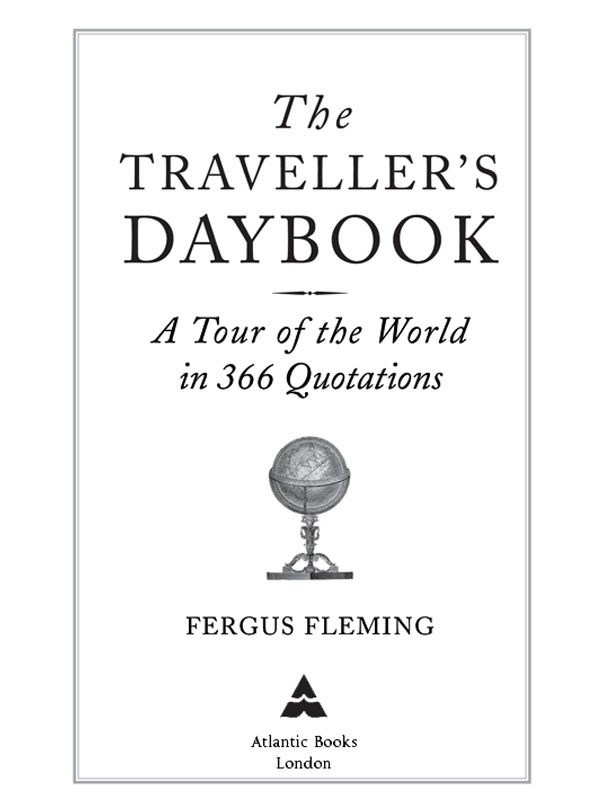

The

TRAVELLERS

DAYBOOK

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright in notes and selection of excerpts Fergus Fleming, 2011

The moral right of Fergus Fleming to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The permissions to quote from material in copyright contained on this form part of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The Publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

All images are courtesy of iStock, Shutterstock or public domain.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 184887 813 6

eISBN: 978 085789 928 6

Designed by carrstudio.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

An invitation to edit an anthology of travel writing is a rare privilege. Of all literary genres, travel is one of the most rewarding and diverse. The very act of moving from A to an unknown B seems to bring out the best in authors. Some travel in order to write, some write because they have travelled, while others have such eye-opening experiences that it doesnt matter if they can write well or not. Even in the dullest, most dutiful Victorian tome you can usually detect some stirring of the soul. To be let loose in a travel section of a library and in this case to be paid for it! is a splendid thing.

The challenge set by my publishers was to compile a calendar of extracts written on or, failing that, within the vicinity of each of the 366 days of the year, including the elusive 29 February. The task was both frustrating and stimulating: frustrating because many of the best travel writers do not supply dates; and stimulating because it introduced me to a host of others who do. Take the Marquis de Beauvoir, a soign, globe-trotting teenager of the nineteenth century who began one paragraph with the words: When we left the harem, we went to see the tigers. Or Lafcadio Hearn, a Greek-American in Meiji-era Japan who conjured the magic of sea-demons lurking off its western coast. There is a beautiful melancholy to Joseph Roths description of Berlins parks in the 1920s. And then the irrepressible Nicolas Bouvier, who feared his car had shot its pistons in a Turkish desert, only to find that the knocking came from a landscape of tortoises engaged in their autumn amours. Perhaps my favourite is Archer Crouch, a Victorian engineer who laid submarine cables off the West African coast and was so intimidated by the exploits of greater explorers that he dared not put his name to his journal: his high point, endearingly, was the discovery of a small monument to forgotten soldiers who had died in an out-of-the-way place that nobody had heard of.

Credit for this book must first of all be given to the writers who have made it possible. At Atlantic Books I would like to thank Anthony Cheetham, who came up with the idea for the book; Richard Milbank, who asked me to write it; Sarah Norman and Sachna Hanspal, who ensured its smooth passage through to press; and Mark Hawkins-Dady for his attention to the text. I would also like to thank my agent Gillon Aitken; and the staffs at the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the Kensington and Chelsea Libraries, the London Library and the Royal Geographical Society. I would like further to dedicate this book to the memory of an old friend and colleague, Alan Lothian, who died on 12 September 2010.

FF, London, 2011

JANUARY

1 JANUARY

ALL BY MYSELF, 1900

Isabelle Eberhardt (18771904) was a young Swiss woman, disturbed and prey to addictions, who sought adventure in the Sahara dressed as a man. On the coast of Sardinia, she contemplated in her diary a nomadic future.

I sit here all by myself, looking at the grey expanse of murmuring sea... I am utterly alone on earth, and always will be in this Universe so full of lures and disappointments... alone, turning my back on a world of dead hopes and memories...

I shall dig in my heels and go on acting the lunatic in the intoxicating expanse of desert as I did last summer, or go on galloping through olive groves in the Tunisian Sahel, as I did last autumn...

Right now, I long for one thing only: to lead that life again in Africa... to sleep in the chilly silence of the night below stars that drop from great heights, with the skys infinite expanse for a roof and the warm earth for a bed, in the knowledge that no one pines for me anywhere on earth, that there is no place where I am being missed or expected. To know that is to be free and unencumbered, a nomad in the great desert of life where I shall never be anything but an outsider. Such is the only form of bliss, however bitter, the Mektoub [Fate] will ever grant me, but then happiness of the sort coveted by all of frantic humanity, will never be mine.

I SABELLE E BERHARDT , T HE P ASSIONATE N OMAD .

2 JANUARY

NORDIC AUGURIES, 1895

On this date, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen (18611930) welcomed the start of the year aboard his ship the Fram. Unique among polar vessels, the Fram had a rounded hull that allowed it to rise above the floes rather than be crushed by them. In 1893 Nansen had embedded his ship in the Arctic pack and let it drift with the ice, ostensibly to collect scientific data but also to provide a springboard for an attempt to ski to the North Pole.

Never before have I had such strange feelings at the commencement of the New Year. It cannot fail to bring some momentous events, and will possibly become one of the most remarkable years in my life, whether it leads me to success or to destruction. Years come and go unnoticed in this world of ice, and we have no more knowledge here of what these years have brought to humanity than we know of what the future ones have in store. In this silent nature no events ever happen; all is shrouded in darkness; there is nothing in view save the twinkling stars, immeasurably far away in the freezing night, and the flickering sheen of the aurora borealis. I can just discern close by the vague outline of the