CONTENTS

About the Book

Catching all the fascination and humour of travel in out-of-the-way places, Ones Company is Peter Flemings account of his journey through Russia and Manchuria to China when he was Special Correspondent to The Times in the 1930s.

Fleming spent seven months with the object of investigating the Communist situation in South China at a time when, as far as he knew, no previous journey had been made to the anti-communist front by a foreigner, and on its publication in 1934, Ones Company won widespread critical acclaim.

Packed with classic incidents brake-failure on the Trans-Siberian Express, the Eton Boating Song singing lesson in Manchuria Ones Company was among the forerunners of a whole new approach to travel writing.

About the Author

Peter Fleming was born in 1907 and educated at Eton and Oxford, where he gained a First in English Literature and was Editor of Isis. In 1935, he married Celia Johnson, the distinguished actress, and they had a son and two daughters. He worked briefly in New York before joining an expedition to look for a lost captain in Brazil. This resulted in his first book, Brazilian Adventure, which has been translated into many languages. As a Special Correspondent of The Times, Fleming travelled widely in Eastern and Central Asia. He served in the Grenadier Guards during the war and later commanded the 4th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (T.A.). He received the O.B.E. in 1945 and was High Sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1952. His other books, chiefly on travel and war history, include News from Tartary (1936), The Forgotten Journey (1952), The Siege at Peking (1959), Invasion 1940 (1957), Bayonets to Lhasa (1961) and The Fate of Admiral Kolchak (1963). He died in August 1971.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

To the memory of R.F.

WARNING TO THE READER

The recorded history of Chinese civilization covers a period of four thousand years. The population of China is estimated at 450 millions. China is larger than Europe

The author of this book is twenty-six years old. He has spent, altogether, about seven months in China. He does not speak Chinese

FOREWORD

THIS BOOK IS a superficial account of an unsensational journey. My Warning to the Reader justifies, I think, its superficiality. It is easy to be dogmatic at a distance, and I dare say I could have made my half-baked conclusions on the major issues of the Far Eastern situation sound convincing. But it is one thing to bore your readers, another to mislead them; I did not like to run the risk of doing both. I have therefore kept the major issues in the background.

The book describes in some detail what I saw and what I did, and in considerably less detail what most other travellers have also seen and done. If it has any value at all, it is the light which it throws on the processes of travel amateur travel in parts of the interior, which, though not remote, are seldom visited.

On two occasions, I admit, I have attempted seriously to assess a politico-military situation, but only (a) because I thought I knew more about those particular situations than anyone else, and (b) because if they had not been explained certain sections of the book would have made nonsense. For the rest, I make no claim to be directly instructive. One cannot, it is true, travel through a country without finding out something about it; and the reader, following vicariously in my footsteps, may perhaps learn a little. But not much.

I owe debts of gratitude to more people than can conveniently be named, people of all degrees and many nationalities. He who befriends a traveller is not easily forgotten, and I am very grateful indeed to everyone who helped me on a long journey.

P ETER F LEMING

London,

May 1934

N OTE . Some of the material contained in this book has appeared in the columns of the Times, the Spectator and Life and Letters. My thanks are due to the editors of these journals for permission to reproduce it here in a different form.

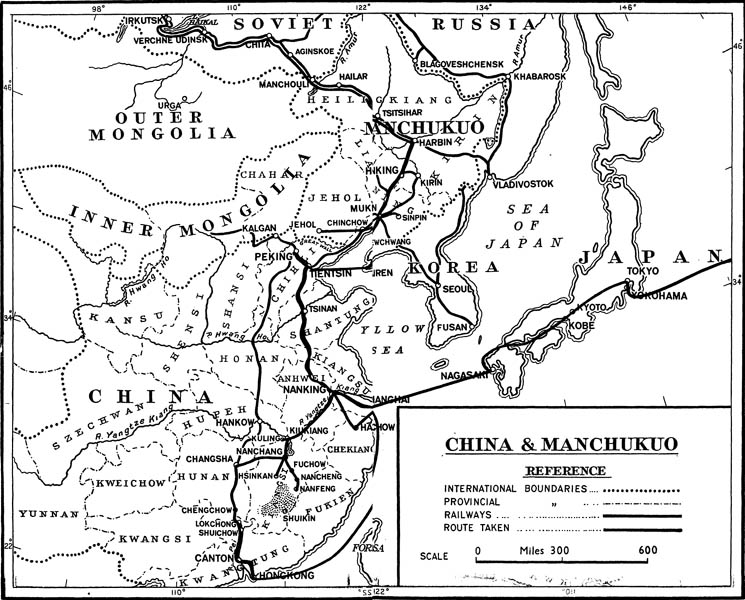

PART ONE : MANCHUKUO

CHAPTER I

BOYS WILL BE BOYS

I ALWAYS READ (I know I have said this before) the Agony Column of the Times.

I was reading it now. It was June 2nd, 1933: a lovely day. English fields, bright, friendly, and chequered, streamed past the window of the Harwich boat-train. Above each cottage smoke rose in a slim pillar which wriggled slightly before vanishing into a hot blue sky. Cattle were converging on the shade of trees, swinging their tails against the early summer flies with a dreamy and elegant motion. Beside a stream an elderly man was putting up his rod in an atmosphere of consecration. Open cars ran cheerfully along the roads, full of golf-clubs and tennis-rackets and picnic-hampers. Gipsies were camped in a chalk-pit. A green woodpecker, its laughter inaudible to me, flew diagonally across a field. Two children played with puppies on a tiny lawn. Downs rose hazily in the distance. England was looking her best.

I, on the threshold of exile, found it expedient to ignore her. I turned to the Agony Column.

The Agony Column was apropos but not very encouraging, like the sermon on the last Sunday of term.

Because it is so uncertain as well as expensive, I must wait and trust. The advertiser was anonymous.

I put the paper down. Normally I would have speculated at some length on the circumstances which evoked this cri du cur; to-day I was content to accept it merely as oracular guidance. We were in the same boat, the advertiser and I; as he (or possibly she) pointed out, we must wait and trust.

From my typewriter, on the rack opposite, a label dangled, swinging gently to and fro in a deprecating way. PASSENGER TO MANCHULI said the label. I wished it would keep still. There was something pointed in such suave and regular oscillation; the legend acquired an ironical lilt. Well, well! said the label, sceptical and patronizing. Boys will be boys.

PASSENGER TO MANCHULI . Had there been anyone else in the carriage, and had he been able to decipher my block-capitals, and had he in addition been fairly good at geography and at international politics in the Far East, that label alone would have been enough (for he is clearly an exceptional chap) to assure him that my immediate future looked like being uncertain as well as expensive. For Manchuli is the junction, on the frontier between Russia and Manchuria, on the Trans-Siberian and the Chinese Eastern Railways; and the latter line had recently been announced as closed to traffic, its ownership being in dispute between Moscow and the Japanese-controlled government of Manchukuo. In short, on the evidence to hand my hypothetical fellow-passenger would have been warranted in assuming that I was either up to, or would come to, no good; or both.

With the possible exception of the Equator, everything begins somewhere. Too many of those too many who write about their travels plunge straight in medias res; their opening sentence informs us bluntly and dramatically that the prow (or bow) of the dhow grated on the sand, and they stepped lightly ashore.

No doubt they did. But why? With what excuse? What other and anterior steps had they taken? Was it boredom, business, or a broken heart that drove them so far afield? We have a right to know.