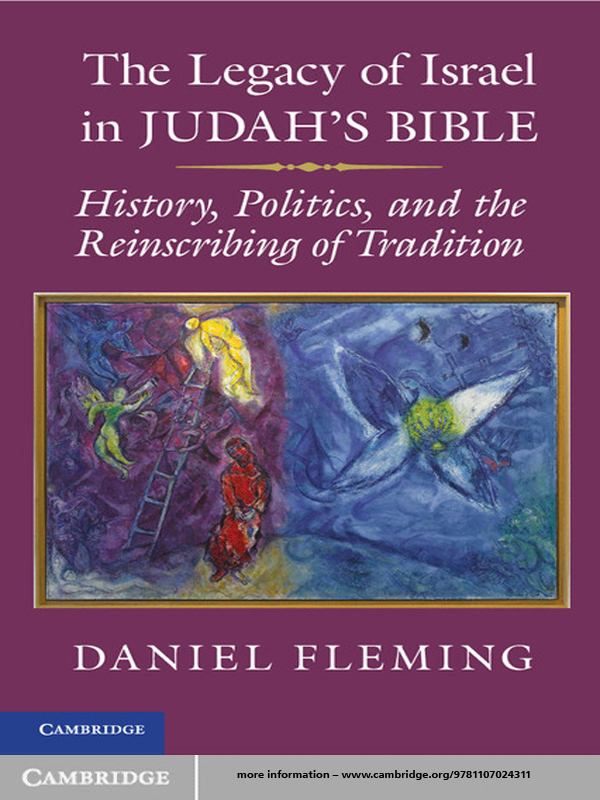

The Legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible

History, Politics, and the Reinscribing of Tradition

The Legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible undertakes a comprehensive reevaluation of the Bible's primary narrative in Genesis through Kings as it relates to history. It divides the core textual traditions along political lines that reveal deeply contrasting assumptions, an approach that places biblical controversies in dialogue with anthropologically informed archaeology. Starting from close study of selected biblical texts, the work moves toward historical issues that may be illuminated by both this material and a larger range of textual evidence. The result is a synthesis that breaks away from conventional lines of debate in matters relating to ancient Israel and the Bible, setting an agenda for future engagement of these fields with wider study of antiquity.

Advance Praise for The Legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible

For decades the field of biblical studies has been engaged in a series of literary and historical debates regarding the Hebrew Bible and ancient Israel, yet there has been little consensus about these subjects. Fleming breaks through this impasse with a remarkably fresh insight into Israel as an association of groups engaged in collective and collaborative politics differing considerably from Judahs more centralized political life. Fleming also explores several important cross-cultural analogies for Israels tradition of collaborative politics from the ancient Near East and traditional societies from Mesoamerica, the American Southwest, and pre-Viking Denmark. For this aspect of his research, Fleming draws heavily on recent theory on power and political organization. This book is a superb piece of scholarship; every chapter marked by deep erudition and engaging insights. No professor or graduate student interested in the Hebrew Bible or ancient Israel can do without it.

Mark S. Smith, Skirball Professor of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies, New York University

Scholarly debate about the early history of Israel has run into the sand. Extreme conservatives and radical revisionists shout across each other with little solid gain. The combination of a thoroughly critical analysis of the written sources together with an informed use of archaeological and other sources has been lacking until now. With his major proposal that we should disentangle the account of Israel from the Bible that has come to us from Judah, Fleming has broken this stalemate. While his analysis will no doubt provoke debate, nobody can deny the authority of the scholarship that he displays.

H. G. M. Williamson, Regius Professor of Hebrew, University of Oxford

Daniel E. Fleming has taught and served in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University since 1990, when he received his doctorate in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University. He currently serves as Chair of the Advisory Committee for NYU's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. The current volume was launched with financial support from a Guggenheim Fellowship (2004). Fleming was also a senior Fulbright Fellow to France (19978) and recipient of a one-year research fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies (20045). He is the author of three books and co-author of a fourth: The Installation of Baal's High Priestess at Emar (1992); Time at Emar (2000); Democracy's Ancient Ancestors (Cambridge, 2004); and, with Sara J. Milstein, The Buried Foundation of the Gilgamesh Epic (2010). Fleming has contributed many articles on topics related to the ancient Near East to a range of professional journals and collected works.

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, So Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City

Cambridge University Press

32 Avenue of the Americas, New York , NY 10013-2473, USA

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107669994

Daniel E. Fleming 2012

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 2012

Printed in the United States of America

A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Fleming, Daniel. E.

The legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible : history, politics, and the reinscribing of tradition / Daniel E. Fleming.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-107-02431-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-107-66999-4 (pbk.)

1. Narration in the Bible. 2. Bible. O.T. -- Criticism, Narrative. I. Title.

BS1182.3.F54 2012

221.67dc22 2011045919

ISBN 978-1-107-02431-1 Hardback

ISBN 978-1-107-66999-4 Paperback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Preface

As we read the Bible, no matter how self-consciously careful we may be, it is natural to let it set our expectations, to provide the framework for understanding its contents. The narrative center of the Bible is a meandering account of the origins and experiences of a people named Israel. In a form that has been connected by various seams, this narrative begins with creation and Israel's ancestry in Genesis; continues through Moses leadership in Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy; and then addresses the life of this people in its own land, through Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. These nine books have been called the Primary History, or the Enneateuch, and no matter the specific process by which they reached their finished form, their guiding story suffuses our sense of what the Bible offers for historical evaluation. Even the isolation of a biblical Israel from whatever existed in history defers to this overarching vision (Davies 1992).

One central idea in this biblical narrative has repeatedly drawn the critical attention of biblical scholars and historians: it has to do with a single people from beginning to end. The two kingdoms of Israel and Judah that are described in the books of Kings ultimately belong to one people of Yahweh, called Israel. Historians in particular have labored to use the Bible cautiously in their reconstructions, and nonbiblical evidence has played a greater role in recent years, especially as archaeology yields more material and drives historical analysis. A handful of nonbiblical texts present two kingdoms that are first visible in the mid-ninth century, first identified as Israel and the House of David and later treated by the Assyrians as Samaria and Judah. From these texts and the findings of archaeology alone, it is not clear how the two kingdoms were related. At this point, the Bible warrants a second look, because its story of a single people ends with an unexpected twist. When we reach 1 and 2 Kings, the last books in what I will call the Bible's primary narrative, the text describes a division into two polities, most often called Israel and Judah. The story begins with one people and takes for granted throughout the ultimate reality of a single people of the god Yahweh, but it ends with the same two kingdoms known from nonbiblical writing. It is clear, then, that two distinct peoples, identified with two separate kingdoms, stand as a historical backdrop to the unified portrait of the Bible's narrative.