Copyright 2007 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to: Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Riley, James, 1777-1840.

INTRODUCTION

Essaouira, Morocco, October 2005. It is twilight, and we are just finishing shooting a dramatic scene on a desolate desert beach. As an Arab cameleer dashes across the dunes with his scimitar poised overhead to strike, the full glowering, burnt-orange African sun silhouettes him and his mount in a vision of solitude and fury. All afternoon a fuming wind has blasted us with sand djinnis, coating every surface. We are ready to go have a whisky in the medina of the nearby walled city to rid our mouths of grit, contemplate the unforgettable image, and plan the next shoot.

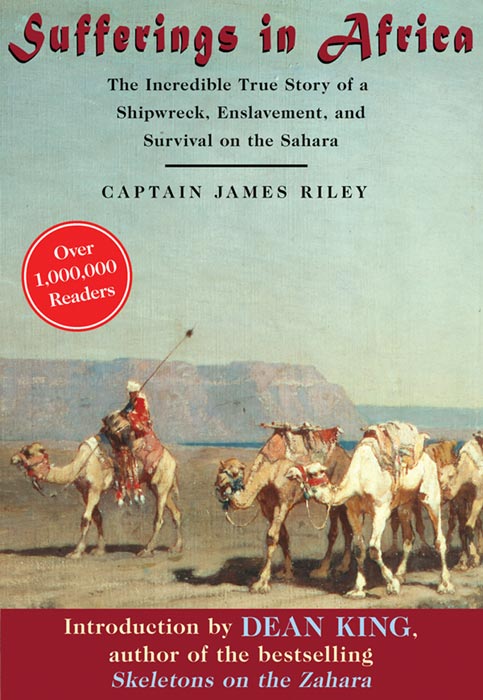

Nineteen decades before we arrived in Essaouira, on the coast near Marrakech, the Connecticut merchant brig Commerce, under Captain James Riley of Middletown, wrecked on the west coast of Africa south of here, beginning one of the most appalling andas recounted in Rileys Sufferings in Africa, the volume you now hold in your handsspellbinding adventures that American citizens have ever endured. After scrambling ashore through stormy seas, the crew of the Commerce, a dozen in all, was attacked by fierce natives, whom they believed to be cannibals. The Commerces, as the sailors would have been known, escaped in their longboat and spent nine days rowing and bailing in heavy seas. Soaked, scorched, and blistered, their clothes and skin hanging in tatters, reduced to drinking urine, they crashed ashore again.

Thats when things got bad. Camel-riding nomads, the fierce Oulad Bou Sbaa (though Riley does not name them), captured and enslaved the sailors and drove them relentles sly across dunes and hardpan in a seemingly endless and pointless desert migration. The sailors were fed little, mostly camel milk. Half naked and broiling under the desert sun during the day, they slept outside at night, like dogs, where they were strafed by the frigid, sand-bearing harmattan. Under these extreme conditions, some would die beneath the lash. Others, led by Captain Riley, eventually mounted an improbable and hair-raising march back to civilization. To do this, Riley first had to convince an Arab trader from the north to risk everything he owned to buy them and lead the way.

Two of the twelve sailors returned to pen memoirs of the ordeal, both published in 1817. While that of twenty-two-year-old able seaman Archibald Robbins, like Captain Rileys, was graphic and sensational and went through many printings, the captains came first and was literarily superior. Evocative and detailed, curious and introspective, it was profound enough for Abraham Lincoln to list it in his 1860 campaign biography (the only one he authorized and reviewed) with the Bible, Pilgrims Progress, Aesops Fables, and biographies of Washington and Jefferson as the books that influenced him during his youth. Henry David Thoreau and James Fenimore Cooper also read and acknowledged Riley.

In its heyday, Rileys memoir had joined rare company, and it had lost little of its power nearly two centuries later when I discovered the largely forgotten work on a shelf of the New York Yacht Club library. After reading it virtually nonstop and then tracking down Robbinss account, I was so moved by the suffering and struggles of these Americans enslaved in a foreign land and by the lessons the story offered regarding todays clash between East and West that I retraced Rileys route in 2001 and retold the story in the book Skeletons on the Zahara (Little, Brown, 2004).

Now I am back in Africa, this time with the History Channel to work on a two-hour special documentary about Rileys remarkable voyage. On the way to the desolate swath of beach where we film the Arab cameleer, I notice the ruins of what appears to be an old fortress. After our work is done, I ask if we can stop there and check it out.

The ruins lie on the coast looking north to the walled city of Mogadore, or Swearah, as locals called it (Essaouira on todays map). An illustration in Sufferings (see page xvi of this edition) shows the square four-towered fortress, where Riley first met William Willshire, the Englishman who paid his ransom. As I explore the place, trying to match Rileys description to what is now left, I recall the emotional meeting between the two men, who came from opposing sides in the only recently ended War of 1812. Willshire, it turned out, did not bear a grudge. A compassionate man, he would risk his own wealth and efforts many times over to help sailors in distress, strangers all, even as it turned out Americans.

Riley had described the fortresss towers as having green tile roofs. These towers have been reduced by time and the elements nearly to piles of rock and dust, but as I poke around the ruins, I discover several small buildings with faded-green tiles clinging to what is left of the roofs. As I hold one in my hand, a frisson runs through me. In the tile, I feel Captain Rileys presence, for he was a keen observer, a man to whom such details mattered. After traveling eight hundred miles across the desert, reduced in weight from a stout 240 pounds to ninety, his life hanging on the thin thread of a lie that he knew a merchant who would pay his ransom on the spothe knew no one in Mogadorehe still noted the green tiles.

Perhaps it was no coincidence that Riley noticed ordinary things. He was not a professional explorer or adventurer. He had not set out to prove a theory and was not seeking fame and glory or deliberately putting himself in danger. He was just a merchant captain trying to feed his wife and five children. He was an ordinary man, who found extraordinary powers of fortitude within, making his ordeal all the more poignant.

Meticulously observant though he was, Riley had his doubters. The veracity of his tale was questioned even in its day, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Too many adventure stories we consider classics are dubious, at least partly fabricated (Slavomir Rawiczs