Copyright 2000 by Patrick Marnham

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This work was originally published in Great Britain as

The Death of Jean Moulin: Biography of a Ghost,

by John Murray (Publishers), London, in 2000.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marnham, Patrick.

Resistance and betrayal: the death and life of the greatest hero of the French Resistance/Patrick Marnham. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-58836-078-6

1. Moulin, Jean, 18991943. 2. World War, 19391945Underground movementsFrance. 3. GuerrillasFranceBiography. I. Title.

D802.F8 M263 2002

940.5344dc21 2001048160

Random House website address: www.atrandom.com

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3

First U.S. Edition

v3.1

Les Franais sont tellement diffrents les uns des autres, comprenez-vous, tellement prts se dchirer! Il fallait bien leur trouver un dnominateur commun. Ce ne pouvait tre que la patrie

CHARLES DE GAULLE

(The French are so different one from another, you see, so quick to tear each other apart. It was essential to find some common cause. It could only be patriotism )

CONTENTS

Introduction

Jean Moulin is remembered in France today as the great hero of the wartime Resistance. Yet few modern heroes remain so enigmatic. Sixty years on, mystery shrouds such elementary facts as his true political beliefs, the manner of his betrayal and even the time and place of his death.

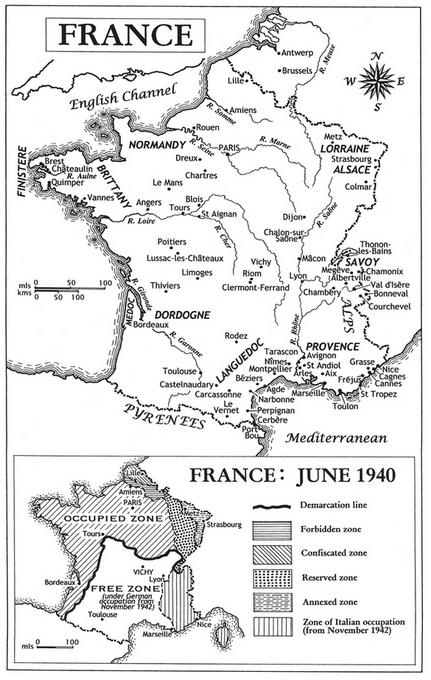

In 1941, Moulinwho had been a senior civil servant before the outbreak of the warslipped over the Spanish border out of wartime France using a passport he had forged himself to reach London and take his place as the most eminent recruit to the cause of the Free French. There he agreed to act as General de Gaulles emissary to the Resistance and was entrusted with the mission of uniting the movement and reforging it as an instrument of national liberation. Despite his high rank he was twice smuggled back into France, where he lived underground and frequently on the run in conditions of grave danger.

By May 1943, Moulin had succeeded in creating a united resistance movement, ranging from the ultra-right to the communists, under his personal political leadership. To achieve this he had had to overcome the bitter rivalries dividing the ambitious individualists who had created the original networks. One month later Jean Moulin was betrayed to the Gestapo and captured in Lyon. Despite the torture he suffered at the hands of the SS officer Klaus Barbie, Moulin remained silent and paid for his courage with his life. Two postwar treason trials held in Paris failed to uncover the identity of his betrayer. Twenty years later, during an emotional ceremony at the Panthon, his heroism was officially recognized and he was consecrated as a national symbol.

Jean Moulin came from what the French call a a republican background. In the undeclared civil war that divided French society during his lifetime and that of his father before him, the Moulin family was always on the progressive side of the argument, egalitarian, anti-monarchist and anticlerical. Moulin first achieved political influence during the 1930s, when the Spanish Civil War led to the formation of the Popular Front, an alliance between radicals, socialists, communists and other anti-fascists.

For many thousands of European and American idealists this exhilarating intellectual adventure was brutally terminated in August 1939, with the news of the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

It was thenin Koestlers mocking similethat the men of the Popular Front faced the bitter truth as did Jacob in Genesis, who awoke on the morning after his wedding night to find that after seven years of struggle he had won not the beautiful Rachel but her hideous sister, Leah. Jean Moulins dedicated support for the Popular Front led to postwar accusations by fellow resisters that his commitment to communism may have survived the Pact and that he may even have been a communist agent. In 1989 Moulins wartime radio operator, Daniel Cordier, outraged by this suggestion, defended the reputation of his old commander in the first of what was planned to be a six-volume study that must be one of the quixotic biographical monuments ever conceived. But despite Cordiers loyal efforts the arguments continue, reflecting the divisions in French society that were established a century ago and persist to this day. In such circumstances it is sometimes easier for an outsider to make out the truth.

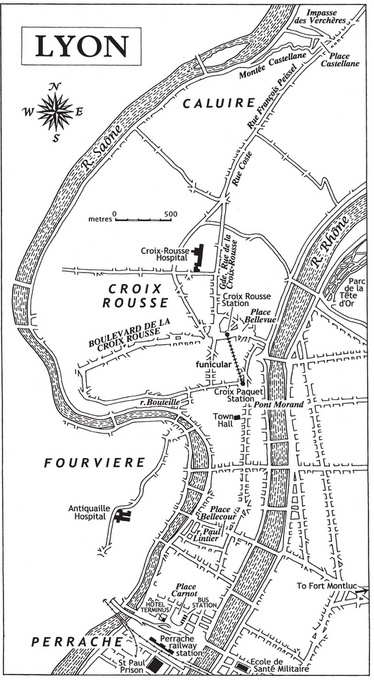

My own interest in the life of Jean Moulin began in the early 1980s when I was writing about the political maneuvering that preceded the trial in Lyon of the man who arrested him, the former SS officer Klaus Barbie. Barbie eventually received a life sentence after being convicted of wartime crimes against humanity. Over the years Barbie made numerous contradictory statements about the raid he had conducted on the house in Caluire and the traitors of the Resistance; none were entirely convincing and it seems likely that when Barbie died in a French prison he revenged himself by taking the truth with him to his grave.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the story of Jean Moulin is that a life that has been the subject of so many inquiries should remain so discreet. We glimpse Moulin in a succession of silhouettes: an incident with some army recruits in Montpellier when he was aged eighteen, an encounter with a brutish gatekeeper, a fragment of verse which is all that remains of a dinner with the depraved poet Max Jacob, some drawings scribbled on a caf tablecloth during the occupation of Lyon. Pieced together, such moments can form the outlines of a mans life; certainly they reveal someone whose vitality and humanity stand in strong contrast to the heroic effigy they lowered into the crypt of the Panthon.

ONE

A Doctors House in Caluire

T he house in Caluire stands today exactly as it stood then, a handsome stone building on the corner of a small provincial square called the Place Castellane. Caluire is a suburb of Lyon, perched on a hill overlooking the sleepy waters of the River Sane. Raised on a terrace slightly above the level of the square, its three floors protected by a stone wall and iron railings, the house has the light gray shutters and dark green creeper of so many French villas of its period.

Today, as then, it is the property of Dr. Frdric Dugoujon. In 1943 Lyon was under martial law, occupied by German forces, but most people tried to carry on as normally as possible. Dr. Dugoujon was among them. In common with the great majority of people he was not involved in resistance. But he had a friend who was a member of the resistance group