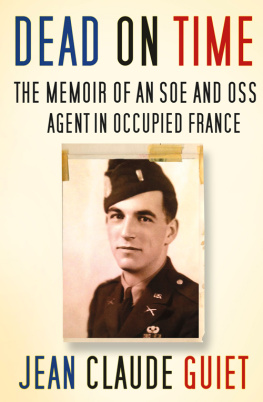

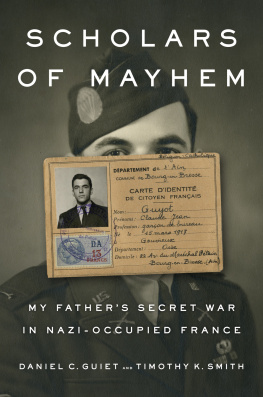

I am deeply indebted to my agent, Mark H. Yeats, for his practical guidance and his vast knowledge of and passion for all things SOE/OSS. His remarkable patience and professionalism was evident at every step of the process. He recognised my fathers memoir as a story that needed to be told and made it all possible.

I thank my editor, Chrissy McMorris at The History Press, who brought this endeavour to fruition with intelligence and sensitivity.

My deepest appreciation to Tania Szab for writing her very thoughtful foreword to this book, for referring me to her agent Mark Yeats and for her kind support.

I am also very grateful to Robert Maloubier for his amazing foreword and for sharing experiences that illuminate my father as a young man.

I owe a great deal to Julie and Ron La Point for their deep personal interest in my fathers story and their assistance to him with word processing. My father referred to his computer as that damned infernal machine.

I am also thankful to Robert Forte, who has a great knowledge of the wireless radio that my father used and strongly supported the publication of this memoir.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY

ROBERT MALOUBIER

One day in May 1944, in London, our boss Major Charles Staunton told Violette Szab, the courier of our team, and myself:

The radio operator who is going to join us is a very young American, born of French parents, a tenderfoot, named Jean Claude Guiet. An OSS issue, he has been trained in the States. They have Special Training Schools similar to ours in the UK, you know. I suggest we have lunch together at Rose, the French restaurant in Soho, tomorrow. You know the place, dont you?

Charles is the boss of our Special Operations Executive (SOE) team, Salesman. He has been on three secret assignments in occupied France. Captured by Vichy police in 1941, he had managed to escape across the Pyrnes to Spain, Portugal and back to England. A former international press correspondent, he is shrewd. The perfect boss and spiritual father for a youngster like me. I spent seven months as a saboteur under his command behind Normandys Atlantic Wall in 1943. We were flown back to the UK in February aboard a small plane of SOEs Moonlight Squadron.

Rose is a typical bistro of Soho, a cosmopolitan district of London. A sort of narrow corridor invaded by kitchen smokes. Crude marble tables, thick earthenware plates. Nonetheless, Rose provides thick juicy steaks, and buckets of crisp chips. The bistro is unlicensed, so guests go and get their fill of thick red wine next door, at the York Minster, Dean Streets famed French pub. His landlord, the Belgian Victor Berlemont, boasts Londons widest moustache: ten inches from wing tip to wing tip!

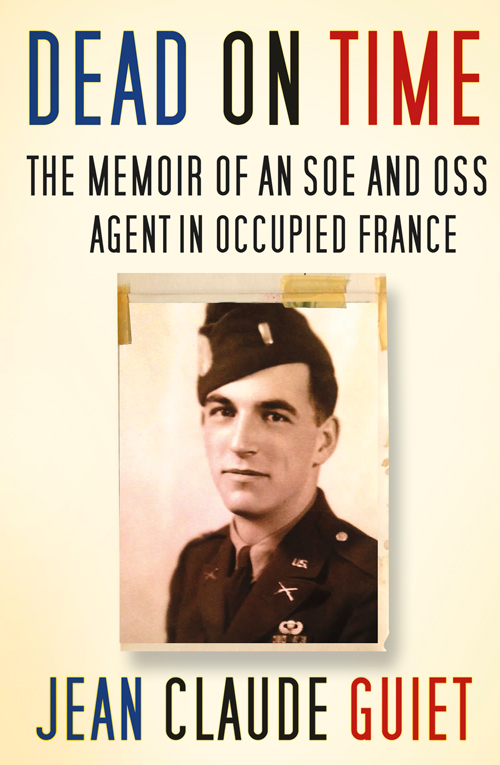

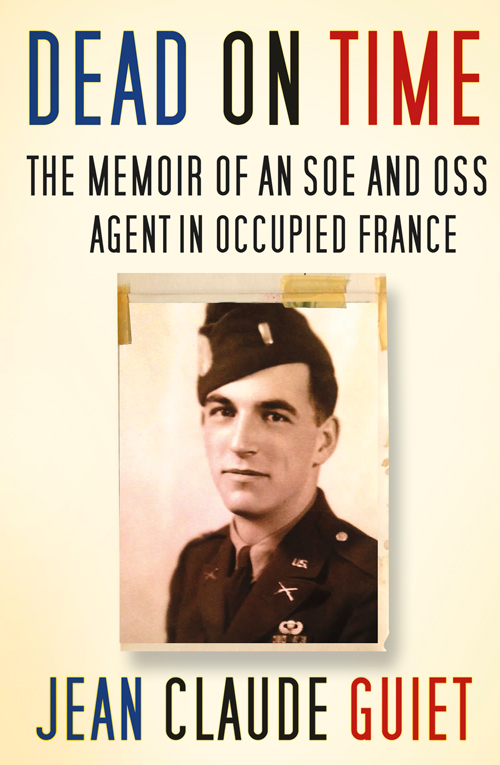

Jean Claude Guiet is dead on time. Impeccably clad in officers pinks, tall, sporty, handsome. Open face, frank grey eyes.

Violette whispers in my ear, A good looker, isnt he?

Jean Claude sips his wine bravely, keeps wolfing his steak down. Mischievously, Violette stops him short. Its horse meat, you know! In the UK, meat is rationed, meat of all origins, but horse meat Knowing how Yanks revere their horses, the noblest conquest of men, she expected him to choke. The lad is unruffled.

So, welcome to the club, says Violette. Now tell us more about yourself.

Jean Claude was born in the Jura region of France, close to the Swiss border. His parents, both professors, settled later in the United States. In June 1940, he was holidaying in France with his elder brother when both were nearly caught by the Germans who had invaded the country. They managed to reach Spain, Portugal and thereafter board a New York-bound steamship. He was approaching graduation from Harvard when Hirohito hit Pearl Harbor. He decided to join the armed forces. There a talent scout noted that he spoke perfect French. The OSS took over. At Camp X, he qualified as a potential secret agent to infiltrate occupied France and was transferred to SOEs Baker Street Irregulars.

From now on, youre one of ours, Violette tells him.

Bi-national, born of a French mother and an English father, Vi is a 23-year-old war widow, and the mother of 2-year-old Tania, who often babbles at her side. Her husband, a French legionnaire , had been killed at El Alamein. He had never set eyes on his daughter. Violette had conceived an irrepressible hatred for the Germans who had killed the man of her life. She had joined the Forces. Spotted as multilingual, she had been invited to join SOEs French Section.

We are members of a team just as close-knit as a bomber crew, going to the cinema together, spending dinner-and-dance evenings at our favourite Knightsbridge Studio Club, playing poker or pontoon a variation on Black Jack at Wimpole Streets SOE hostel.

We were to parachute early June into a communist maquis group in Limousin, central France. Staunton was to assess its fighting strength, its will to fight and see that it was properly supplied with weapons and equipment to be dropped from England. I was to train its men in guerrilla warfare, lead groups of them to road and rail ambushes, organise air drops and sabotage roads and railroads. Jean Claude was to be in charge of radio transmissions, Vi was to liaise with nearby SOE networks.

In early June 1944 we made for Hazells Hall, a stately Edwardian manor nested in a huge and elegant park in Cambridgeshire, one of the French Section departing stations. We made two or three aborted attempts. On the eve of 6 June, our B-24 four-engine Liberator bomber took off for good. We played poker throughout the three- or four-hour flight to Limoges. Alas, above our assigned dropping zone, the captain came to us: Sorry, lady and gentlemen. The reception committee that was to welcome you is missing. See for yourself: no lights on the ground! My orders are clear: I am not to drop you blind! Here we go, back to UK

Using our chutes as a pillow, we lay down on the bomb compartment floor and fell asleep. From time to time I woke up, paid a visit to the cockpit, had a chat with the crew, looked out to dense cloud. Through gaps in the thick clouds one could see a foamy sea ripped by ships wakes. I wondered loudly, What are they?

Well, ships wakes mean that a convoy is passing by across the Channel, replied the captain. Thats all.

Past dawn we touched down at Tempsford, our Moonlight Squadron airbase. A car took us back to Hazells Hall. A few minutes later, we were fast asleep.

Around noon a hullaballoo woke me up. The bar was seemingly going wild with merrymakers bursting with laughter, crying out with joy, yelling and singing their heads off as if they had been drinking the night through. The beaming batman who brought a cup of tea a few minutes later spelt the news: Its D Day gentlemen. We have landed this morning!

So that explained why the Channel was rippled by the wakes of a convoy, one amounting to 5,000 vessels landing 140,000 men on the beaches of Normandy!

We parachuted on the night of 7 June. Jean Claude tapped a safe arrival message out to London.

Two days later, disaster struck: Violette, sent by Staunton to liaise with the head of a nearby SOE network, ran into the vanguard of the ravenous SS Panzer Division Das Reich , which had been ordered by Rommel to leave its station in southern France and help contain Normandys beachhead. She was captured. We were never to see her again.

Though we were grieving, there was a war to be won. So Jean Claude went on dispatching hundreds of messages and eventually joined me in ambushing enemy convoys. Months later, Limoges German garrison surrendered. We drove to Paris. Jean Claude was most welcome at my familys home in Neuilly, a northwestern suburb of Paris. Soon after, he was called back to the States.

Next page