This book has been published with the help of a generous donation from Philippe Camu.

This book has been published with the help of a generous donation from Batrice Corra do Lago.

An anonymous donor provided generous support for this publication.

Cet ouvrage, publi dans le cadre dun programme daide la publication, bnficie du soutien de la Mission Culturelle et Universitaire Franaise aux Etats Unis, service de lambassade de France aux EU. (This work, published as part of a program of aid for publication, received support from the Mission Culturelle et Universitaire Franaise aux Etats Unis, a department of the French Embassy in the United States.)

English translation copyright 2016 by Yale University.

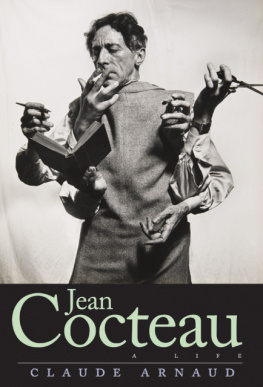

Originally published in French as Jean Cocteau. ditions GALLIMARD , Paris, 2003.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Postscript Electra type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300- 17057-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930231

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Photographs courtesy of the Comit Jean Cocteau: Jean Cocteau as a boy; Cocteaus mother, Eugnie, with her two elder children, Marthe and Paul; Cocteau with Marie Laure; Jean Cocteau, or Fame at the Age of Eighteen; douard Dermit, leaving the mines of Lorraine.

for Edmund White

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

I tremble, I die, I begin again every morning.

Jean Cocteau to Max Jacob, March 1926

A writer doesnt dance, or play drums in a bar. He creates his works in solitude and abandons them only to devote himself to the great problems of his time. We like thinking of creative geniuses as preoccupied more by world events than by the sets of his new play. But Jean Cocteau, though sensitive to the dramas of other individuals, was less concerned with the collective fate of men. Contrary to his suffering nature, his good education meant that he always tried to put himself forward as happy and detached. This internal conflict, along with the more dramatic events he experienced over his lifetime, as death haunted him more and more, led him to grow ever more attentive to his close relationships rather than current events. Cocteau also didnt play the commonly imagined role of the artist in another sense: whereas other artists of his generation typically tried to pass themselves off as rebels or nonconformists, he accepted all prizes, like a child conscious of his parents need for diplomas.

Abroad, Cocteau was fted as the embodiment of early twentieth-century France. F. T. Marinetti and Ezra Pound, Rainer Maria Rilke and Thomas Mannmany celebrated this prodigy who evoked this uniquely French spirit of intelligence and irony. Novelists like Alejo Carpentier and Ernest Hemingway encouraged their ex-pat friends, condemned to observe Paris from across the Atlantic, to read him; he embodied the Parisian for the Cuban Picabia, and the delight of Europe for the American Glenway Wescott. From Tokyo to Havana, Cocteau was the symbol of 1920s France, echoing the innovation and liveliness of the decade. (Charles Pguy, the well-known patriotic writer, said of his compatriots: The peoples of the earth find you light [lger] because you are a quick people.) Young American and Russian film directors cited Le sang dun pote or La belle et la bte among the works that had the greatest influence on them, thirty years before campus rebels and rock fans identified with Les enfants terribles, Thomas limposteur, or Opium.

But Cocteaus fame in France dwindled. The reputation of the writer whom Mayakovsky had visited during his first trip to Paris became increasingly undermined by his protean activity, his rivalry with Andr Breton, and the art pompier style that weighed over his last period and influenced his ceramic Orpheuses. Unevenly respected, easily hated, almost always suspected of being inferior to his reputation, Cocteau is often reduced to the coq--lne that his name unfortunately evokes.

Throughout his lifetime, Jean Cocteaus brilliant forays into theater, drawing, or sculptureall of which were imbued with the old Wagnerian dream of total artwere viewed poorly. Since good seats in posteritys waiting room are precious, his originality was challenged; people who had not a single one of his talents accused him of fraud, ascribing some of his poems to Max Jacob, the avant-garde poet of Le cornet ds, and some of his drawings to Picasso: Picasso, whose powerful charisma always made him seem a genius, even though the painter pillaged from his neighbors.

Thanks to Cocteaus homosexuality, his all too obviously bourgeois origins, and his intensive social life during his lonely formative years, rejection of his work has persisted like a class or racial prejudice. Instead of taking the trouble to read, watch, or experience his entire body of work, as a way of plunging into his abundant imagination, people fall back on well-worn labels like acrobat and Jack-of-all-trades. Worse than a pote mauditan artist damned or doomedCocteau is little read and poorly thought of, victim of an intellectual laziness by an audience that, despite professing otherwise, reduces him to his fancied nature. Apparently Einstein was right: it is harder to break a prejudice than an atom.

No major critic has ever taken the time to analyze Cocteaus work. Universities take little interest in him, this dunce who failed his bac twice.where people understood early on the profundity of a work whose themes form a unique constellation. This is especially true across the Atlantic, where the Surrealists invective never had an impact, and where Cocteau, that icon of the counter-culture, is recognized as the innovator who, along with Buuel, introduced dream in cinema.

Widely underestimated, like poetry itself for half a century, Cocteau the poet, finally published in a Pliade edition, deserves a premier spot, from Plain-chant to Lone. The autobiographical essayist as well is remarkably lucid and astute, in works from La difficult dtre to Journal dun inconnu, as is the memoirist of Portraits-souvenir. Although his works are rare and short, the novelist Cocteau remains excellent, too, as books from Le grand cart to Le livre blanc attestwhile the choreographer Cocteau is often surprising, and the artist is occasionally brilliant. Though the film director and man of the theater veered at times from excellence to catastrophe, even Cocteaus failures in these areas remain surprisingly personal.

Next page