Many of the places visited in this book are open to the general public. Some are in private hands with no right of access. Others are operated by bodies like the National Trust. Some took many approaches before access was agreed. Its always best to make contact well in advance before visiting, and of course sometimes you will have to accept no for answer.

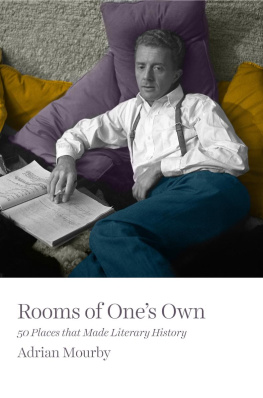

V irginia Woolf famously said that, if she is to write fiction, a woman must have money and a room of her own.

This book explores how male and female writers have over the last two centuries found rooms that inspired them to write, from Tennessee Williams garret in New Orleans to the room with a view that E.M. Forster coveted in Florence.

En route I was able discover something of Damon Runyons New York, Graham Greenes Saigon, and George Sands Venice.

Not every great writer or every room that has witnessed great literature has made it into these 50 chapters. This was very much a personal quest in pursuit of writers who interested me and I didnt want to spend too much time in birthplaces that have been turned into well-meaning museums.

For some of the authors in this book, sitting in the right room was all-important. Marcel Prousts housekeeper claimed that having to relocate from the apartment where he began la recherche du temps perdu exacerbated his ill-health and hastened his death, leaving that ambitious novel sequence incomplete. Victor Hugo spent a fortune turning his house on Guernsey into a very personal Hugo theme park.

For other writers the room can become a location in their fiction. H.G. Wells set one of his bestselling works, Mr Britling Sees It Through, in his own house in Essex. Olivia Manning used her own Cairo flat in the Levant Trilogy. But others had no need for their subject matter to be in front of them. James Joyce wrote exclusively about Dublin while sitting in his favourite Paris restaurants.

Over the last few years Ive visited rooms where the authors presence is almost palpable in the arrangement of every individual object, and others that seem to bear no relationship to the author or the work produced there.

Some writers have preferred to work in a favourite caf J.K. Rowling is only a recent example in a line that stretches back well beyond Sartre. Oscar Wilde liked to write and entertain in expensive hotels but Hemingway and Nol Coward stayed in the best hotels around the world simply because they could. They could write well regardless of their surroundings.

Ive also followed my writers into pubs, apartments, holiday cottages and homes that are now literary museums.

There are some surprises along the way: young Norman Mailer, staying in his parents apartment, trying to have a conversation by the mailboxes with the diffident playwright who lived downstairs and concluding that Arthur Miller could go to hell; Erich Maria Remarque locked in the bathroom by Marlene Dietrich when the Nazis came to visit; a delirious Somerset Maugham overhearing the manageress of his hotel asking the doctor to remove him to hospital as a death would be bad for business.

This book consists of 50 literary pilgrimages to London, Oxford, Paris, Berlin and St Petersburg, as well as to Italy, America, North Africa and the Far East. I didnt just want to write about writers beavering away in the familys spare room so I followed many on their travels because writers do love to travel. Sometimes they are seeking the ideal place in which to work, sometimes they are escaping from life at home. Often they are travelling because their success makes it possible and they know all they need is a pen and paper or laptop to continue writing and so they seize on invitations with alacrity.

There is always something to be learned when you visit the place where a book was written. Sometimes the location features directly in what ends up on the page, but more often than not its significantly altered. We expect writers to be good at their craft and we like them to be inspired by their surroundings, but we cant expect them to be honest as well.

Adrian Mourby, 2017

HOTEL DANIELI, VENICE GEORGE SAND (180476)

I arrived in Venice one chilly January many years ago when the Adriatic was seeping, slowly but relentlessly, across Riva degli Schiavoni. It was exactly 160 years previously that Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin picked her way along this quayside. It wasnt difficult to discover her story. She is commemorated by an inscription within a particular bedroom in Venices first commercial hotel.

Aurore Dupin was one of Hotel Danielis earliest celebrity guests. When she arrived in January 1834 she was trailing scandal and her new lover, the poet Alfred de Musset.

Today Aurore is better known as George Sand, a pen name she adopted in her twenties, just as she adopted masculine attire and male smoking habits. At the age of 27 she left her husband and entered upon a four-year period of rebellion that included affairs with prominent writers and the production of a large number of books. That same year, 1831, she published her first novel, Rose et Blanche, written in collaboration with her then-lover Jules Sandeau, but for her next novel Indiana (1832) she adopted the pen name George Sand. By 1833 Sand had moved on to an affair with the young poet and dramatist Alfred de Musset.

Seven years older than the 23-year-old poet, Sand was keen that they should travel together to Italy where she wished to set her next book. This meant leaving behind her two children (aged five and ten) but the novelist was more concerned with getting the blessing of de Mussets mother for their journey. The two women met in Sands carriage outside Mme de Mussets Paris home. Evidently Maman was overwhelmed by Sands eloquence and promises to take great care of the young man.

The couple took a carriage from Paris to Marseille where they boarded a steamer to Livorno, arriving in January 1834 to a very grey Venice. They took a suite of rooms at the Danieli in what is now Room 10, overlooking Riva degli Schiavoni.

By the time the lovers had unpacked, their six-month romance was cooling. On the journey south Sand had shocked de Musset by her conversation, regaling other passengers with the fact that she was born within a month of her parents marriage, and with steamy stories of her mothers affairs during the Napoleonic Wars. George Sand courted outrage.

In 1834 the commercial hotel Danieli was still something of a new venture in Venice. For centuries this building close to the Doges palace had been known as Palazzo Dandalo. By the time of Napoleons forcible dissolution of the Venetian republic in 1797, the owners had ceased to maintain it. In 1822 an entrepreneur from nearby Fiuli called Giuseppe Dal Niel rented the piano nobile (first floor) of Palazzo Dandalo. In it he accommodated paying guests. By 1824, business was good enough to convince Dal Niel that there was a market for such a venture in Venice and he bought the entire building, lavishly restoring it and converting it into a hotel, to which he gave his Venetian nickname, Danieli.

As a palazzo of the nobility, the buildings main entrance had been to the side on Rio del Vin for gondola access, but as a hotel it needed a door directly onto the quayside of Riva degli Schiavoni. Dal Niel remodelled this facade to create a Gothic doorway and it was on the first floor immediately above this door that George Sand and Alfred de Musset took a suite with superb views. On a clear day you could see beyond the island of San Giorgio di Maggiore to Lido.