W HEN THE N ATIONAL F OOTBALL L EAGUES TEAM OWNERS met at the Victoria Hotel in midtown Manhattan on a cold Monday morning in December 1934, the media contingent covering the event consisted of a single photographer. Not one of New Yorks major newspapers bothered to send a reporter. And the one photographer did not stay long.

After fifteen years in business, the NFL was still languishing on the fringe of Americas sports scene. Millions of sports fans around the country followed baseball, college football, horse racing, and boxing, but many did not even know a professional football league existed. A meeting of the men who ran the league could not possibly produce news that a majority of fans cared about.

A day earlier at the Polo Grounds in New York, the NFL had staged a championship game for just the second time. Before then, the league had simply recognized the team with the best win-loss record as that years champion. But some teams played more games than others, and ties were commonplace, complicating the calculations. To end the confusion, the owners had decided to split their teams into two divisions and match up the division winners in a single game that determined the league title. They hoped the championship contest might one day become a landmark event, like baseballs World Series.

The game at the Polo Grounds, a renowned baseball venue, had mixed results. A brutal ice storm hit New York, limiting the crowd to slightly more than half of the stadiums capacity. That was disappointing. But the game itself was memorable. The visiting Chicago Bears, undefeated and heavily favored, built a lead and seemed in control until the New York Giants switched from cleats to sneakers after halftime to improve their footing on the icy field. The Giants proceeded to score four straight touchdowns and win by a wide margin.

Some of the other team owners had attended the game as a show of support, and now they were meeting to review their season, consider rule changes, and present a championship trophy to Tim Mara, who owned the Giants. The second-floor conference room quickly filled. Mara, tall and grinning, was among the early arrivals. Known in New York sports circles more as a horseracing bookmaker and boxing promoter than as a football team owner, he was accompanied by his twenty-six-year-old son, Jack, who handled the Giants business as the teams president.

George Halas, who owned and coached the Bears, also arrived early along with his older brother. A fiercely competitive midwesterner who had played for the Bears until he was thirty-four years old, Halas was in no mood to congratulate the Giants again after praising them in his postgame interviews with reporters the day before. But his scowl gave way to a sporting smile; Tim Mara was his rival on the field but a good partner in the football business, deserving of a handshake.

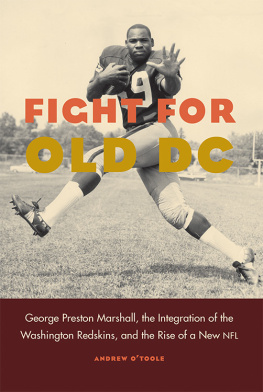

Wearing a high-collared suit and round glasses, Joe Carr, the leagues president since 1921, sat at a head table, ready to run the meeting. Also present were Bert Bell and Lud Wray, former University of Pennsylvania football teammates who co-owned the Philadelphia Eagles, one of the leagues newest teams; George Preston Marshall, an opinionated laundry magnate who owned the Boston Redskins; and Art Rooney, a diminutive, cigar-chomping sportsman and gambler who owned the Pittsburgh Pirates. The owners of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Detroit Lions rounded out the group.

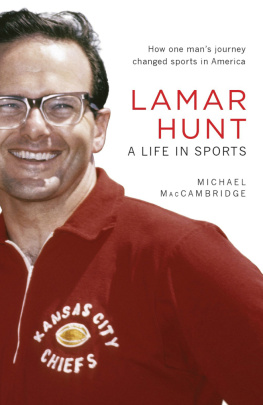

Joe Carr (with glasses) hands the 1934 championship trophy to Jack Mara, as Tim Mara smiles. George Halas stands by Carrs right shoulder. (Associated Press)

to the elder Mara and presented his son with the Ed Thorp Memorial Trophy, a silver-plated cup named for a well-known referee, rules aficionado, and equipment supplier who had died earlier that year. The lone photographer on hand, representing a wire service, snapped a photo that would run in the