The mission of NPR is to work in partnership with member stations to create a more informed publicone challenged and invigorated by a deeper understanding and appreciation of events, ideas, and cultures. To accomplish our mission, we produce, acquire, and distribute programming that meets the highest standards of public service in journalism and cultural expression; we represent our members in matters of their mutual interest; and we provide satellite interconnection for the entire public radio system.

Cokie Roberts covering Congress in 1983 (NPR photo).

by Cokie Roberts

Were going to talk to our listeners just the way we talk to our friends, Susan Stamberg remembers the legendary Bill Siemering telling his skeleton staff at one of their first meetings. National Public Radio had just been created, and Bill, the brains behind All Things Considered, was its first program director. Susans reflections on the birth of NPR find an echo in David Folkenfliks rumination on the future, as he considers what makes us unique: People are given the chance to speak in their own voices.

For forty years, it is that sense of the con-nection and friendship with listeners and with storytellers speaking in their own voiceswhether they be servicemen and -women in Afghanistan, students in Atlanta, people devastated by a massive earthquake in China, or senators in Washingtonthat has served as NPRs hallmark. And what friends we have made over the last four decades! Now some thirty million strong, they not only listen, they give money. They make NPR possible. When people ask why I keep getting up at 5 every Monday for Morning Edition, I answer simply, Because of the listeners. If you want to be heard by young people, farmers, the chief executives of the Fortune 500, members of Congress, players in the media, and especially moms, NPRs the place for you. Those of us who have been around for a long time constantly have the experience of some youngor not so youngperson coming up to us and saying, I grew up listening to you. (They dont mean it to sound as bad as it does.) And we always joke: Your mother made you listen in the car, didnt she? Somewhat to their embarrassment, they admit its true.

This history chronicles those growing-up years from the Little Radio Network That Could to whats now the major source of news for millions of people around the world. It reminds us of the major events of those years and the people who brought them to us, along with memories of some of the non-news contributors. Longtime listeners will probably find themselves smiling as they remember some of those names, people like Kim Williams and Daniel Pinkwater. Most of the people in these pages are still with NPR, still connecting to their friends at the other end of the broadcast line, or the Internet, or the iPhone.

In his chapter about the 1970s, Noah Adams recalls Susan Stambergs Watergate coverage. Reading about the 1980s, no one will have to struggle to remember Linda Wertheimer or Nina Totenberg or Scott Simon as John Ydstie describes the Reagan Revolution, the appointment of the first woman to the Supreme Court, and the fighting in Central America. It might, however, come as a surprise to learn that Robert Siegel was once behind the scenes as an editor and manager long before he took the helm at All Things Considered. Other editors, managers, engineers, producers, and support staff have played essential roles over these forty years, especially the two EllensWeiss and McDonnell who came as kids and ended up basically running the place.

Any history of NPR must be more than one of news events and the people who reported them; it must also serve as a salute to quirkiness. Noah Adams playfully provides a list of stories from the 1970s that includes bed of nails champ, four-year-old Italian singer, and Julie Nixon Eisenhower breaks her toe, along with Mideast turmoil, national medical health insurance, and computer datingfive part series. Noah repeats what he calls a mantra of the Siemering era: Celebrate the human experience. And, as you read through the decades, you realize thats exactly what NPRs been doing all these years.

Along the way, that celebration has earned NPR countless awards, but this isnt a paean to our accomplishments, though some have been significant indeedSylvia Poggiolis Peabody Award, for instance, for her coverage of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. Rene Montagne tells us that what pleased Sylvia wasnt the award, but the fact that her horrific stories about rape as a weapon of war went a long way toward formal recognition of rape and sexual violence as war crimes and crimes against humanity, punishable by an international court. In writing about the 1990s, Rene looks admiringly at the intrepid women like Sylvia, Deb Amos, and Anne Garrels, who rushed to fields of battle, microphones at the ready, to bring us stories of human suffering and triumph from one war zone after another.

As good reporters, we cant avoid NPRs failures how, in the 1970s, the network decided not to produce Garrison Keillors wildly popular A Prairie Home Companion and, in the 1990s, made a similar dumb move when considering whether to run Ira Glasss This American Life. Fortunately, Wait Wait Dont Tell Me! came along at the end of the decade to join Car Talk as a refuge from traditional NPR earnestness, and we are now treated weekly to an alternative version of Carl Kasell. In looking at our history, theres also no way to avoid painful episodes, like the financial crisis that almost sunk us in 1983, or the abrupt departure of Bob Edwards in 2004, or the economic situation that forced the cancellation of News and Notes, The Bryant Park Project, and Day to Day with Alex Chadwick and Madeleine Brand in 2008.

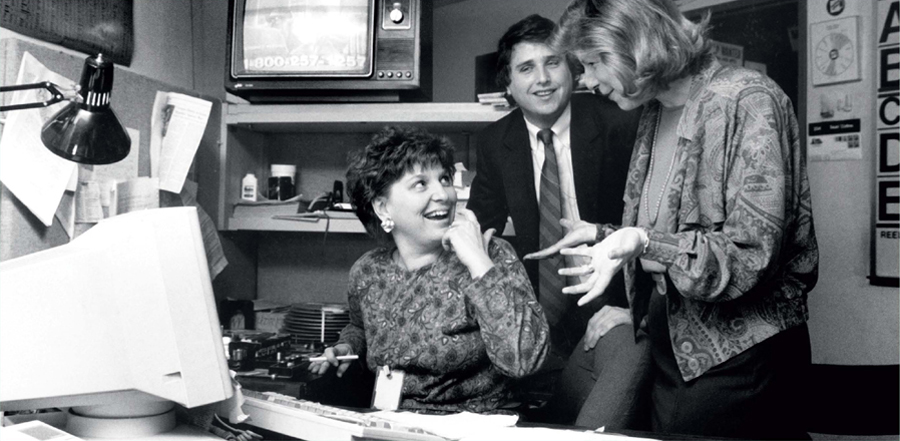

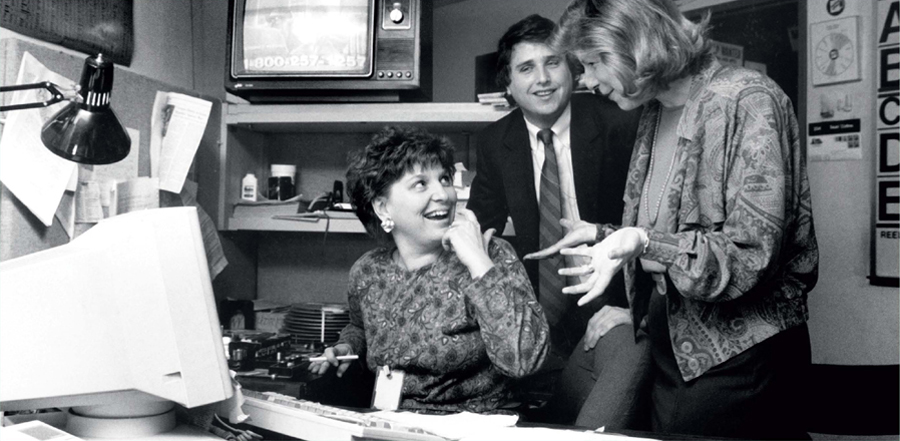

Ellen McDonnell, Michael Richards, and Nina Totenberg in 1980 (NPR photo).

There were plenty of scary moments over the years as wellBill Drummond under fire in Beirut; Scott Simon hiding from gunfire in El Salvador; Rene Montagne escaping thugs in South Africa; Neal Conan captured during the first Persian Gulf War; Lourdes Garcia-Navarros rear window, tire, and laptop destroyed by bullets in the second Iraqi war; Ivan Watson barely avoiding a bomb in Baghdad. And there were the horrifying moments. Michael Skolers description of the scene at a church in the Rwandan countryside during the genocide of 1994 is not one that anyone who heard it has ever forgotten. Neither is Melissa Blocks 2008 live account of the earthquake that shook Chengdu, China. Both stories, and so many others, make it starkly clear that a picture is not, in fact, worth a thousand words. As Susan Stamberg is fond of saying, radio has the best pictures.

From Susans essay of remembrance through Davids look into the future, the history of National Public Radio merges with the history of American journalism over the last forty years. We look back on the time when NPR relied on journalists from newspapers to bring us eyewitness accounts from across the world and realize that many of those journals no longer can afford foreign bureausits now NPRs reporters around the globe that provide information to other news organizations. We laugh about the days when we cut our audiotape with razor blades and pieced it together with splicing tape and took apart telephones to attach little alligator clips in order to file from the field, compared to todays digitized editing and filing. And, as we commemorate the past, we cant help but be concerned about the future. Changes in technology present challenges as well as opportunities, and we dont know where they will lead. But one thing we do know as we march into the decades ahead: We will keep talking to our friends and giving them the chance to say their piece. Together we will celebrate the human spirit.