Table of Contents

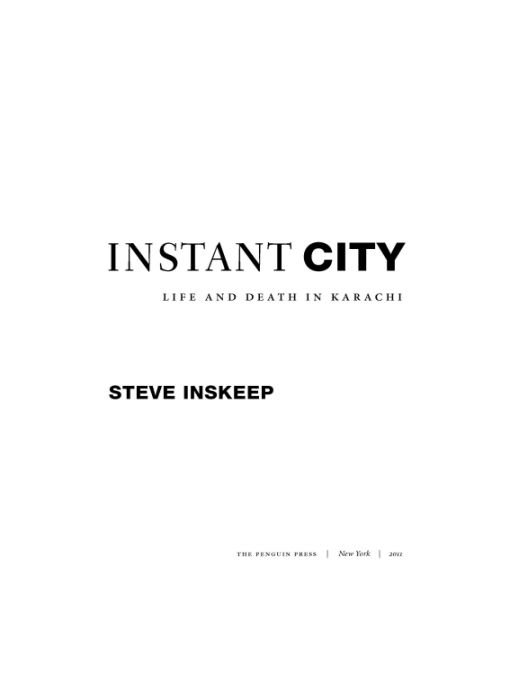

FOR CAROLEE,

who put up with the author and his absences

A NOTE ON SPELLING

English transliterations of South Asian names evolve. The province that includes Karachi, for example, was Sind in 1947 and is Sindh today. While I have used modern spellings, any quoted material preserves the spelling from the original source.

Many boys in Karachi stand in traffic holding birds. The birds hop up and down in little nets. The boys hop between cars, offering the birds for sale. If a driver is having a hard day, or a hard life, and wants to do a good deed to gain the favor of God, he rolls down the window to pass a boy a few bills. Having collected this ransom, the boy sets a captive bird free.

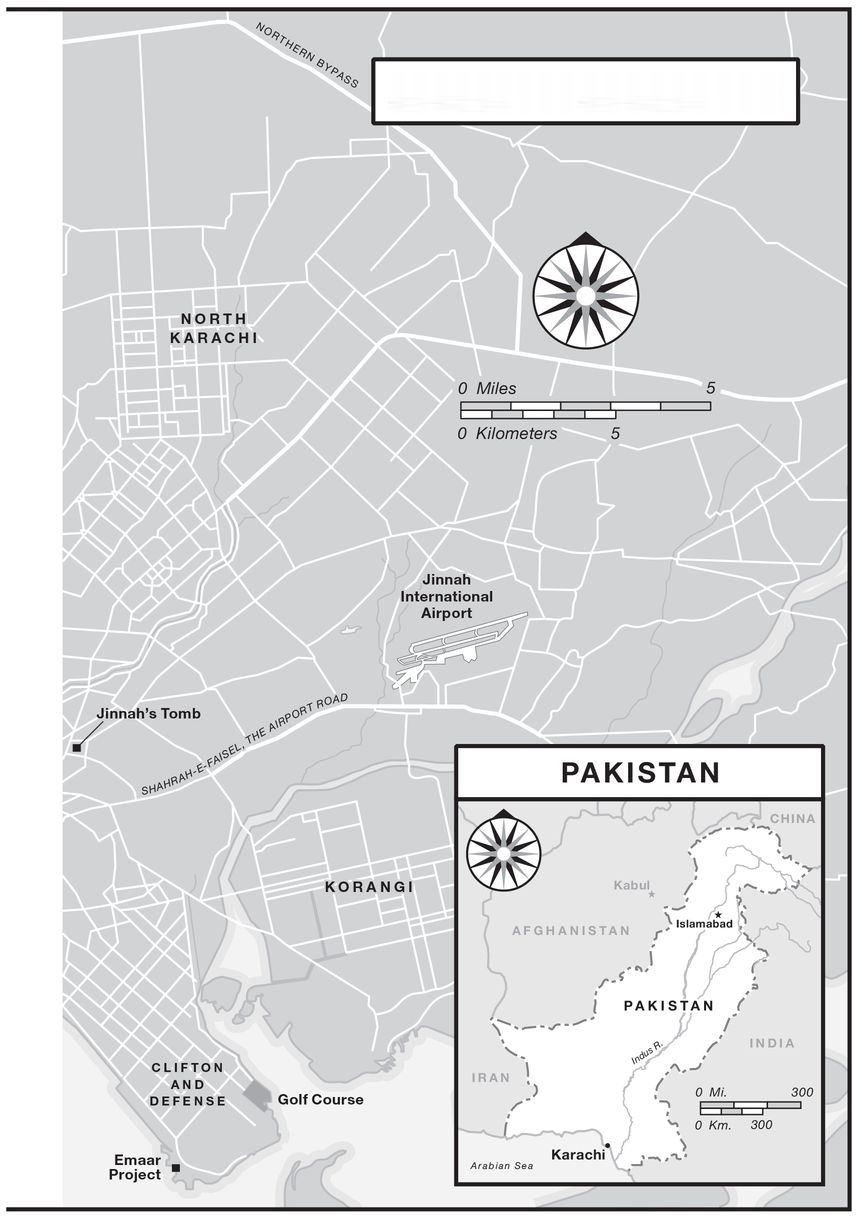

KARACHI, PAKISTAN

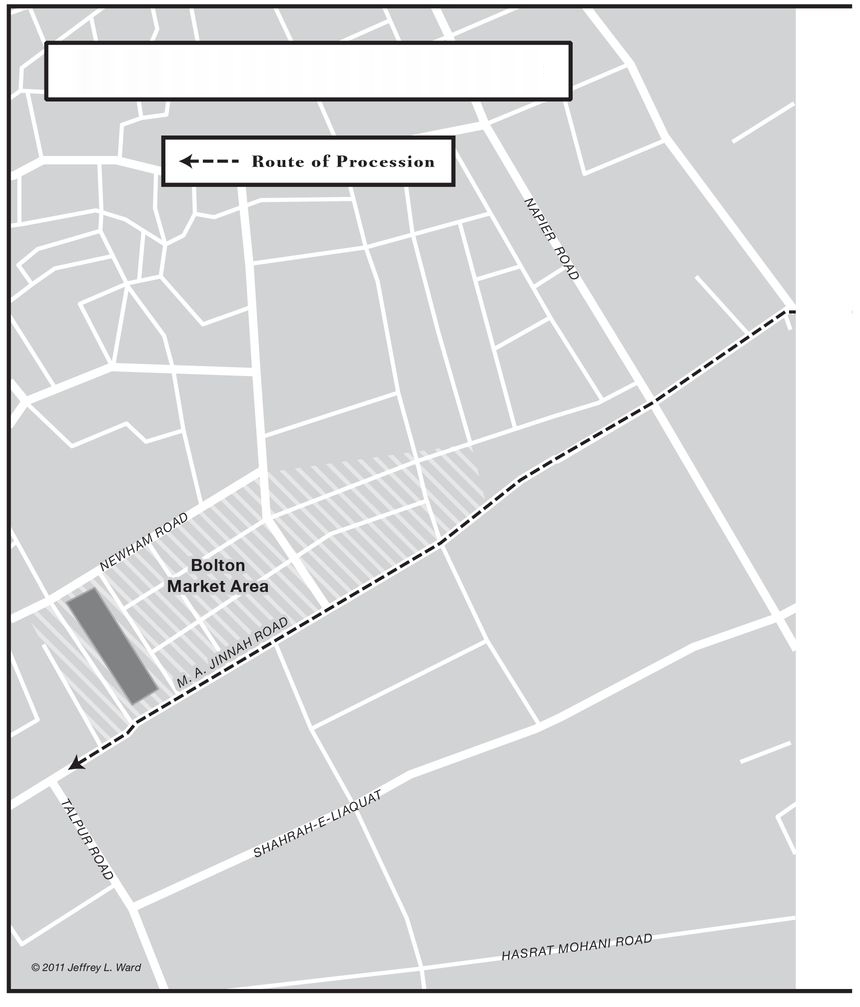

ASHURA PROCESSION, 12-28-2009

NORTH OF NORTH KARACHI

Karachi as we know it appeared in a blink.

Nineteenth-century maps show a dot labeled Karachi, or Kurrachee. But this place was a tiny fraction of the city that exists today.

At the end of World War II, Karachis population was around four hundred thousand.

Today its at least thirteen million, one of the larger cities in the world.

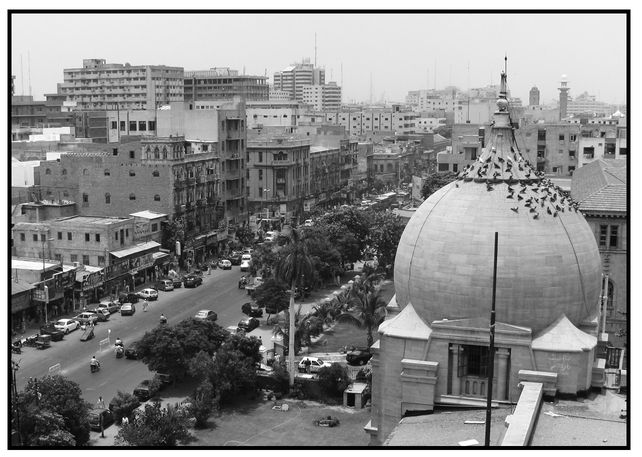

Once I saw this giant metropolis from the roof of the old city hall. The building is an arch-windowed, rambling pile of reddish stone, which dates to the era when the British controlled Karachi as part of their Indian empire. Its design blends the cultures of rulers and ruled. The businesslike lower floors could be facing some European square, but on the roof I was standing amid a series of South Asian onion-shaped domes. A flock of birds settled on the dome to my right, clustering up near the point.

A city employee beckoned me to a door. It led us into the clock tower. We barely had room to step inside, because the floor was covered with thousands of municipal documentsbuilding designs, memos on land use, and maps from the previous century. Past administrations had filed the old papers by dumping them in a pile so enormous that it interfered with the dangling weights that drove the clock.

Stepping over dusty pages at the edge of the pile, we climbed the stairs that circled the clockworks and emerged on a balcony below a clock face. Karachi lay below us like an unfolded map. Motorcycles whined on the street below. One of the office buildings to my right was covered in checkerboard squares of yellow and black.

Above central Karachi.

To my left, busy streets stretched away until they vanished in the haze. The low buildings that lined those streets were shades of khaki and gray, their colors washed out by pollution and the sun.

Eight miles away, I knew, the broad streets cut through North Karachi, which was built in the 1960s as a distant suburb. The expanding city promptly filled the intervening space.

Then it continued beyond.

Today many people live in New Karachi, a sprawling area to the north of North Karachi. Others live miles farther north, in areas even newer than New Karachi.

What spread out before me was an instant city: a metropolis that has grown so rapidly that a returning visitor from a few decades ago would scarcely recognize it. The instant city retains some of its original character and architecture, like Karachis city hall, but has expanded so much that the new overshadows the old.

For most of history, the overwhelming majority of the worlds people lived in the countryside. The global population remained heavily rural even after American and European cities industrialized and grew in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Now the balance has shifted within the span of a single life. Since the aftermath of World War II, the urban population has grown by close to three billion people. Urban dwellers became a majority of the global population around 2008, and many urban areas are still growing.

This trend has produced the instant city, which I define as a metropolitan area thats grown since 1945 at a substantially higher rate than the population of the country to which it belongs. In the United States the population has doubled, but Los Angeles and its suburbs more than tripled. Houston has expanded more than sixfold, and its exuberant growth is modest compared with the developing world. Istanbul is about ten times its previous size. rmqi, a business hub for western China, is about twenty-three times more populous than the estimate for 1950. And then theres Karachi. Conservative estimates suggest that its at least thirty times larger than in 1945meaning that there are at least thirty residents today for every one at the wars end.

This kind of growth reflects more than natural increase, the number of births over deaths. Its true that the global population ballooned in recent decades, an epic trend that contributes massively to the expansion of cities like Karachi. But thats not the whole story. The city has grown too quickly for that. Modern cities also add population by sprawling into rural areas, which is part of what I was seeing from the clock tower: Karachi swallowed hundreds of villages that used to be miles out in the countryside. But even this cannot fully explain the instant city.

Something more is happening: the city is attracting migrants. People arrive from rural areas or from other countries. They work in new industries and build new homes. They bring diverse customs, languages, or religious practices, and they make the older inhabitants tense. Lifelong residents and newcomers alike jostle for power and resources in a swiftly evolving landscape that disorients them all.

In recent decades, the most significant movements to cities have come in Africa and Asia. Karachi has been a destination for some of the most dramatic migrations of all.

No one metropolis could capture the full variety of the worlds growing cities, but Karachi is representative in several ways. Its on the Asian coastline, where massive urban growth is under way. Its modern foundations were laid during the age of European colonialism. Its great expansion coincided with the postwar collapse of empire, when industrialization attracted people to the cityas did the desperation of people seeking shelter from political or economic catastrophes.

And its surprising to learn how often Karachis course has been influenced by trends, ideas, or investment from other cities. Its a listening post where we can take in a global conversation.

Within this one metropolis, we find a range of possible options for the future of the instant city. Traveling across the landscape visible from the city hall balcony, we can encounter anything from shining glass towers to chaotic violence. Lately, Karachi has seen a little more glass, and a lot more violence. Migrants have come from all over Pakistan, concentrating the energies and sorrows of an entire troubled nation in one place under the sun.