Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photographs by the author appear on insert pages .

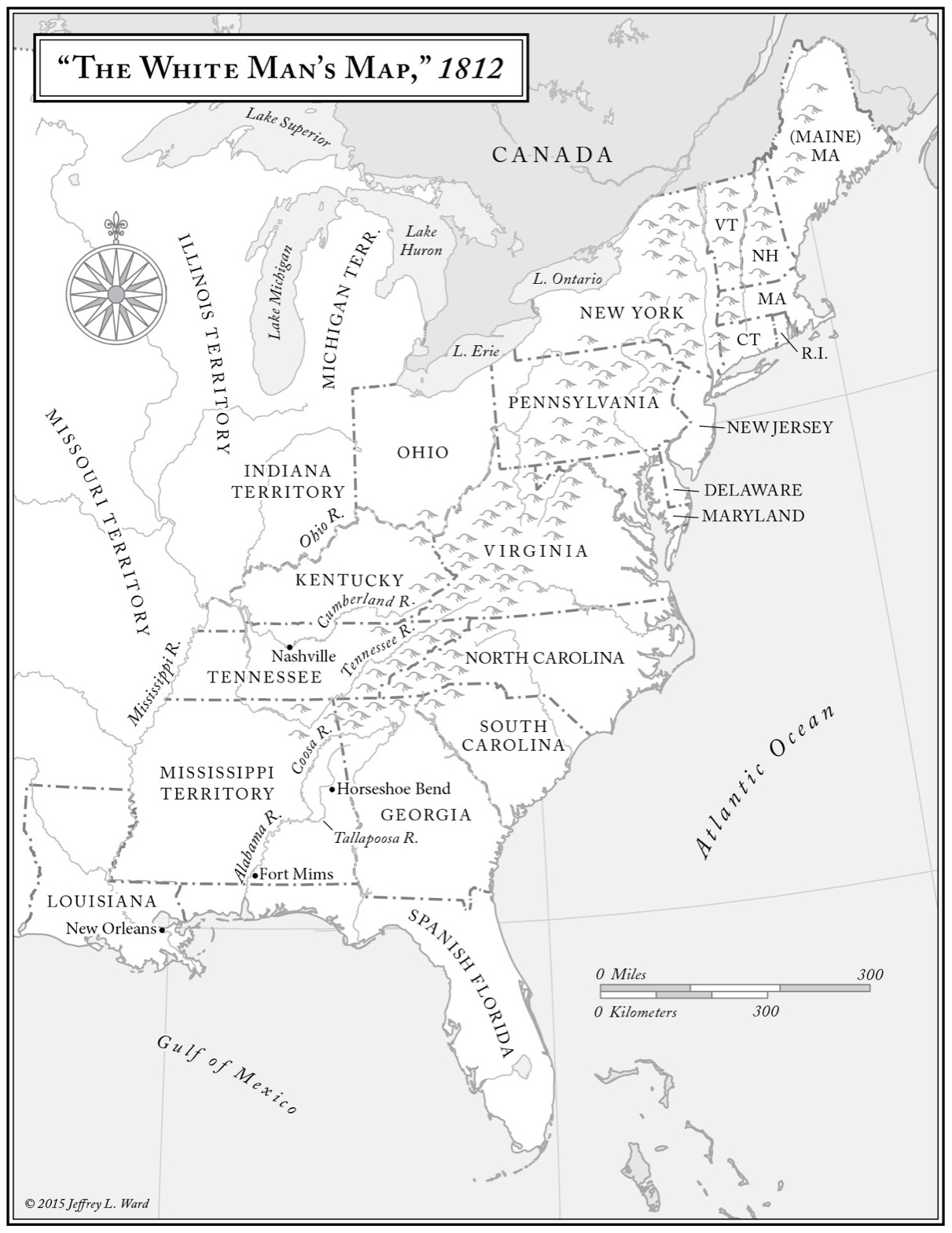

by Jeffrey L. Ward

Those who profess inviolable truthfulness must speak of all without partiality and without hatred.

Prologue:

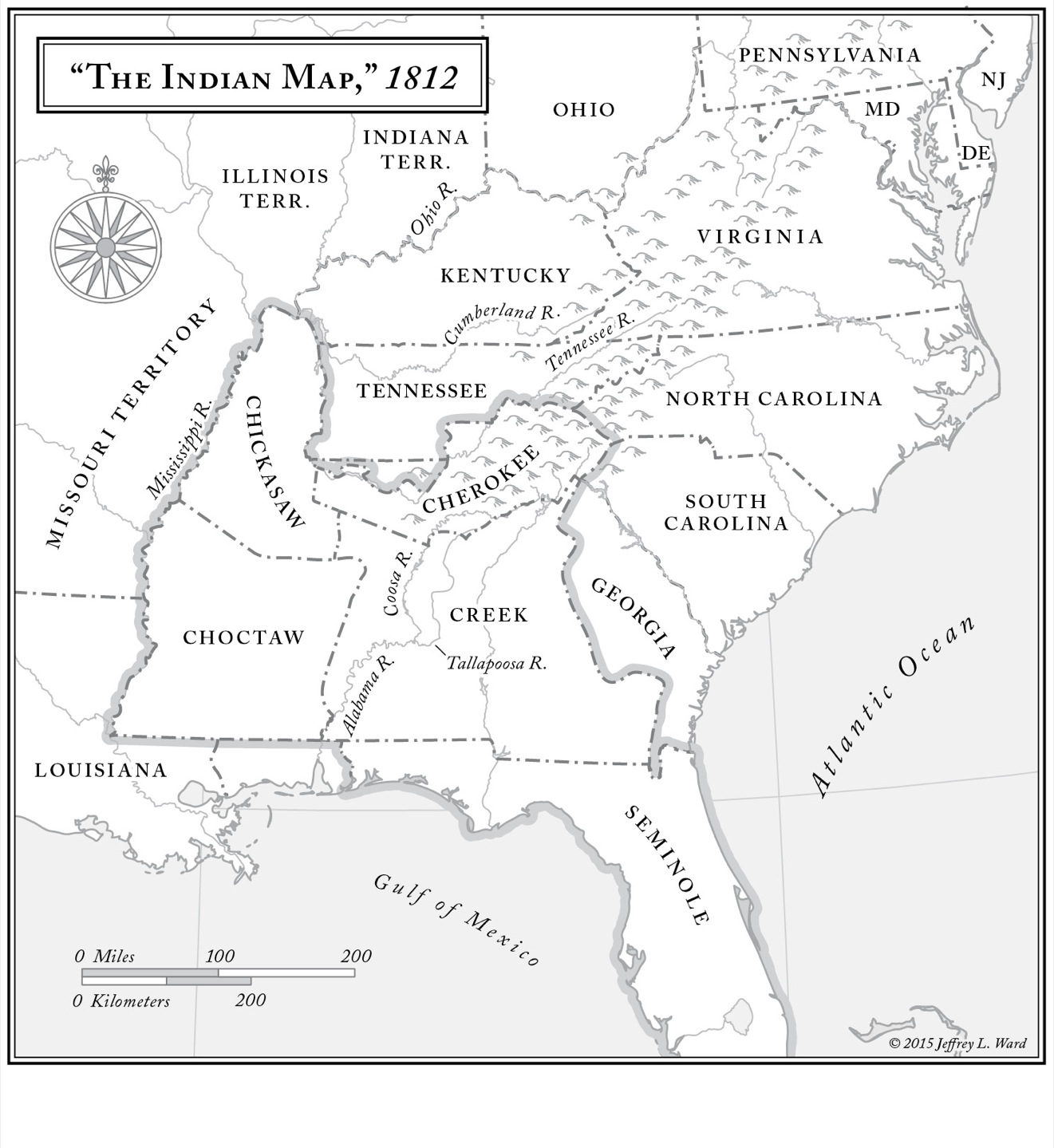

The Indian Map and the White Mans Map

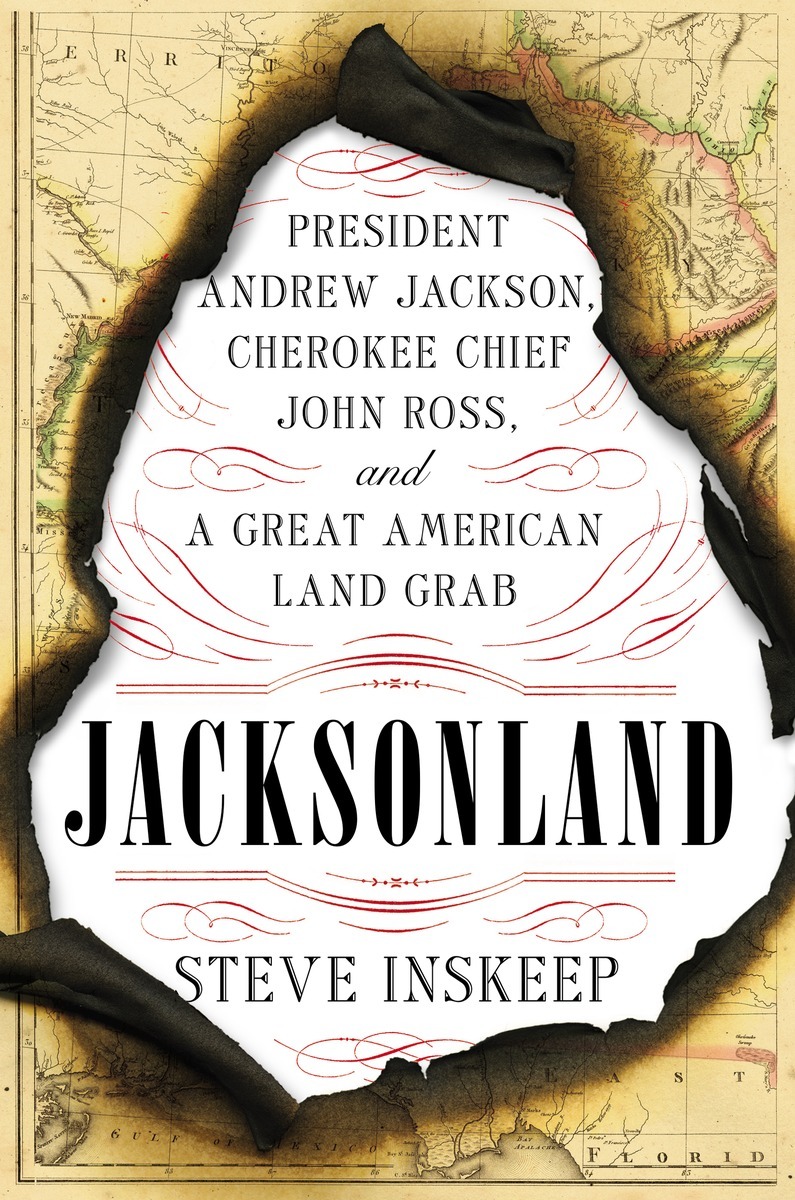

T his story follows two men who fought for more than twenty years. They fought over land in the American South, which is where they lived, though some said it wasnt big enough for the two of them.

One man was Andrew Jackson, who became a general, then president, then the man on the twenty-dollar bill. Those honors merely hint at the scale of his outsize life. The other man was John Ross, who was Native American, or Indian as natives were called. He became principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, though this title, too, fails to capture his full experience.

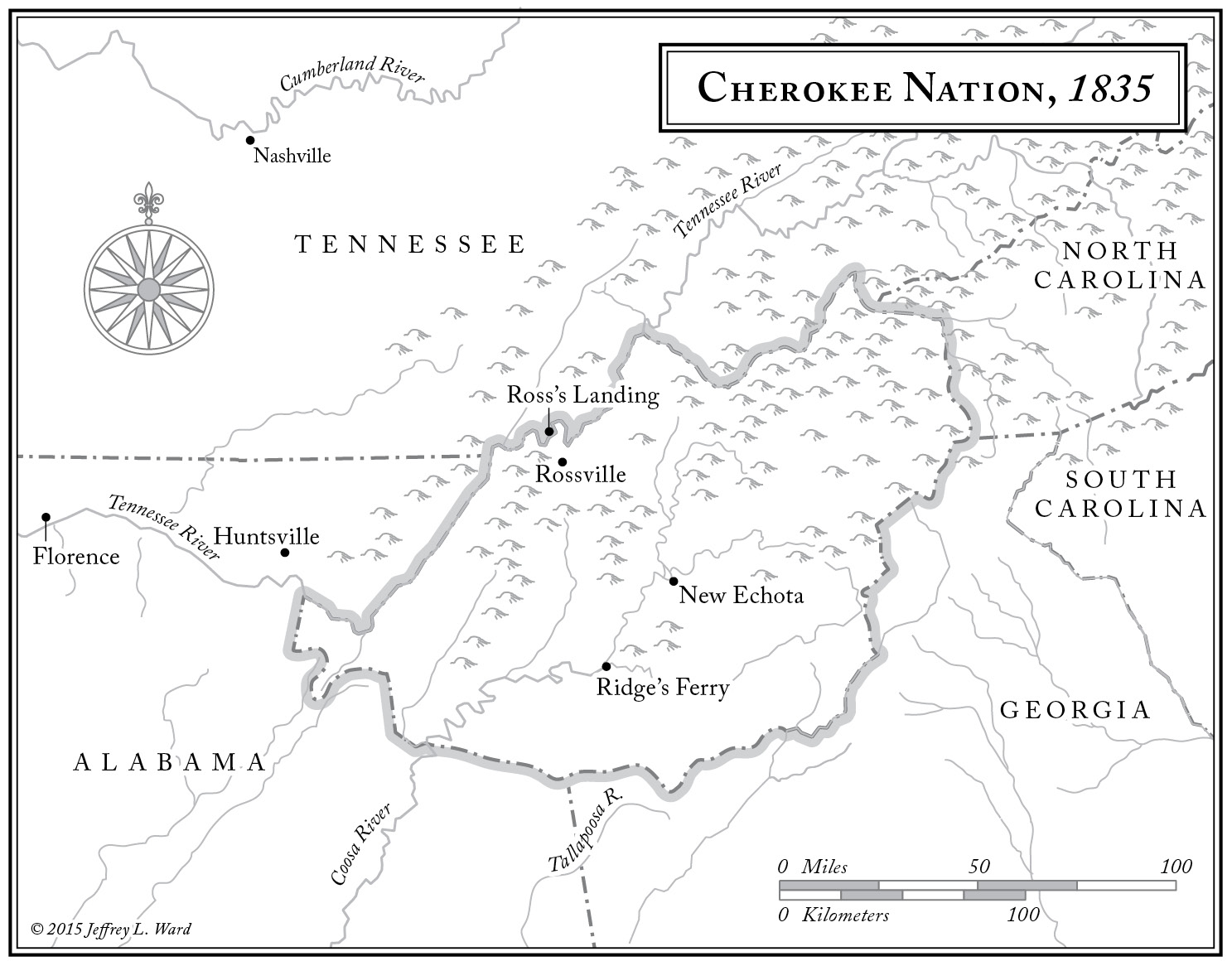

Before he was chief, and before he met Jackson, Ross was a young man navigating his complex and perilous world. That is how we first encounter him. At the age of twenty-two, he bought a boat. It was a wooden flatboat, essentially a raft with some housing on the deck. And on that boat, near the end of 1812, he set out on the Tennessee River. Starting somewhere around the site of present-day Chattanooga, the boat and its crew floated westward with the current, a speck on the water, dwarfed by riverside cliffs that marked the rivers passage through the Appalachians.

Ross was traveling several hundred miles, toward a band of Cherokees living west of the Mississippi. He intended to sell them the cargo on his boat: calico, gingham, buttons, beaver traps, and shotguns. But the westward course of the Tennessee River had a way of testing travelers. Ross struggled to navigate currents so perilous that they had ominous names such as Dead Mans Eddy and the Suck. He grew so frustrated after days on the water that he stopped at a riverside settlement to sell his boat, trading for a keelboat that was narrower and more maneuverable. His crew heaved their cargo from one boat to the other. Then Ross and crew crashed through forty miles of whitewater known as Muscle Shoals, scraping on shallows and passing islands piled with driftwood. At last the water calmed, and the boat followed the rivers great bend northward toward the Ohio.

Anyone covertly studying the boat would have seen four men on board. Ross was black-haired, brown-eyed, slight but handsome. Each of his three companions could be described in a phrase (a Cherokee interpreter, an older Cherokee man named Kalsatee, and a servant), but Ross was harder to categorize. He was the son of a Scottish trader, whose family had lived among Cherokees for generations in their homeland in the southern Appalachians. Ross was an aspiring trader himself. Yet he also had a solid claim to his identity as an Indian. A man of mixed race, he had grown up among Cherokee children and, in keeping with Cherokee custom, received a new name at adulthood: Kooweskoowe, said to be a species of bird.

Whether he was a white man or an Indian became a matter of life and death on December 28, 1812. In Kentucky, as Ross later recorded in a letter, we was haled by a party of white men. The men on the riverbank called for the boat to come closer.

Ross asked what they wanted.

Give us the news, one called back.

Something bothered Ross about the men. I told them we had no news worth their attention.

Now the white men revealed their true purpose. One shouted that they had orders from a garrison of soldiers nearby to stop every boat descending the river to examin if any Indians was on board as they were not permitted to come about that place. Come to us, the men concluded. Or well come to you.

Ross didnt come.

Damn my soul if those two are not Indians, one of the men shouted, referring to two of Rosss crew. The man added that he would gather a company of men to pursue and kill them.

Ross came up with an answer: These two men are Spaniard, he called back.

The white men demanded the Spaniards prove their identity by speaking Spanish. Peter, the servant, actually could, but the white men still insisted it was an Indian boat & mounted their horses & galloped off.

Ross had to assume the white men were serious. The United States had declared war on Britain that year, and some native nations had joined the British side, killing white settlers, fighting alongside British troops, and throwing the frontier into turmoil. The white horsemen would not pause to find out that Rosss Cherokees were loyal to the United States. The Cherokees could travel in only one direction, and would have little chance to escape if the men on horseback arranged an unpleasant reception downstream.