The Cherokee Diaspora

GREGORY D. SMITHERS

The Cherokee Diaspora

An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS/NEW HEAVEN & LONDON

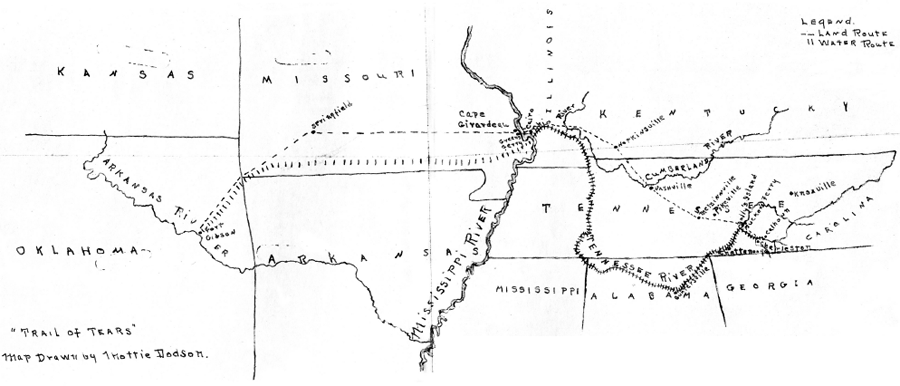

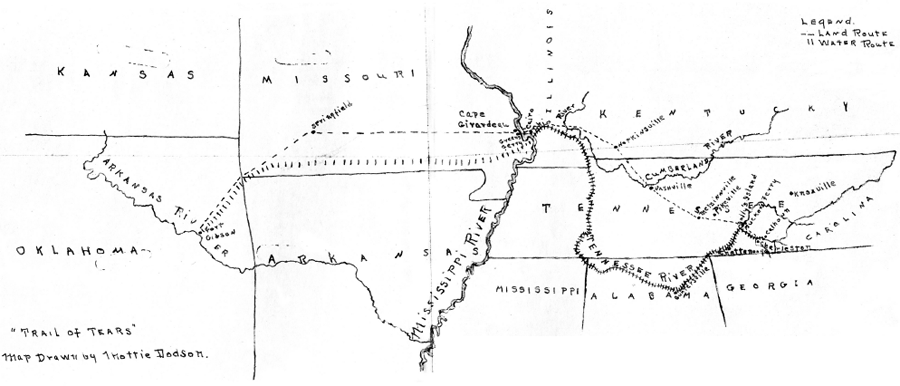

: Mottie Dodsons Map of the Trail of Tears, M1990.052, ca. 1830s, Oklahoma Historical Society, Research Division. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Dawes Commission recognized Dodson as Cherokee by blood, a legal designation that Cherokee officials disputed. Still, Dodson dedicated herself to preserving Cherokee history. The overland route shown in this map depicts the Northern Route (ignoring Benges and Bells routes), which ran south of the Northern Route, while the water route that Dodson attempted to portray in actuality took Cherokee exiles west along the Tennessee River, south down the Mississippi River, and west to Indian Territory along the Arkansas River. Dodsons cartographic imprecision is a poetic reminder of the uncertainties of life in the nineteenth-century Cherokee diaspora.

Copyright 2015 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Minion type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-16960-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933298

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lamar Series in Western History

The Lamar Series in Western History includes scholarly books of general public interest that enhance the understanding of human affairs in the American West and contribute to a wider understanding of the Wests significance in the political, social, and cultural life of America. Comprising works of the highest quality, the series aims to increase the range and vitality of Western American history, focusing on frontier places and people, Indian and ethnic communities, the urban West and the environment, and the art and illustrated history of the American West.

Editorial Board

Howard R. Lamar, Sterling Professor of History Emeritus, Past President of Yale University

William J. Cronon, University of WisconsinMadison

Philip J. Deloria, University of Michigan

John Mack Faragher, Yale University

Jay Gitlin, Yale University

George A. Miles, Beinecke Library, Yale University

Martha A. Sandweiss, Princeton University

Virginia J. Scharff, University of New Mexico

Robert M. Utley, Former Chief Historian, National Park Service

Recent Titles

Sovereignty for Survival: American Energy Development and Indian Self-Determination, by James Robert Allison III

George I. Snchez: The Long Fight for Mexican American Integration, by Carlos Kevin Blanton

The Yaquis and the Empire: Violence, Spanish Imperial Power, and Native Resilience in Colonial Mexico, by Raphael Brewster Folsom

Gathering Together: The Shawnee People through Diaspora and Nationhood, 16001870, by Sami Lakomki

Natures Noblemen: Transatlantic Masculinities and the Nineteenth-Century American West, by Monica Rico

Rush to Gold: The French and the California Gold Rush, 18481854, by Malcolm J. Rohrbough

Home Rule: Households, Manhood, and National Expansion on the Eighteenth-Century Kentucky Frontier, by Honor Sachs

The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity by Gregory D. Smithers

Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian, by Don C. Talayesva, edited by Leo Simmons, Second Edition

Before L.A.: Race, Space, and Municipal Power in Los Angeles, 17811894, by David Samuel Torres-Rouff

Geronimo, by Robert M. Utley

Wanted: The Outlaw Lives of Billy the Kid and Ned Kelly, by Robert M. Utley

Forthcoming Titles

American Genocide: The California Indian Catastrophe, 18461873, by Benjamin Madley

For Brooke

Contents

Prologue

On a cold, bleak winter afternoon in July 2001, I sat in the reading room of the National Archives of Australia in Canberra, Australias capital city. Cradled on the desk in front of me was immigration file A12513. On a single page, printed on both sides, was an application for residency, dated December 17, 1965. The document had an unmistakably musty smell, but its contents, both typed and handwritten, were clearly legible. The information in that file revealed to me that an American family wished to settle just outside of Brisbane, the capital city of Queensland, under the Commonwealth of Australias General assistance passage scheme. In its bureaucratic format there existed nothing exceptional about this application; that is, until I began reading the genealogical information attributed to the matriarch of the familya family consisting of eleven people. Cherokee Meeks nee Taylor was her name. At first I thought nothing of it. I read on. Cherokee Meekss mother, Georgia A. Taylor, was White, English decent and Quarter Cherokee Indian.

Cherokee Meeks was, to use a phrase that was still part of the racial lexicon in the United State and Australia during the 1960s, a mixed-blood. Did Georgia worry that government demographers might define her daughters Cherokee ancestry out of existence? In giving her daughter the name Cherokee, what values, historical images, and memories did Georgia Rogers have in mind? What did she think it meant to be Cherokee? More importantly, what did she want her daughter to think it meant to be Cherokee?

It is not clear who penned the genealogical notes on that 1965 application for residency. It might have been a faceless bureaucrat, or it could just as easily have been her husband, Fred Tucker Meeks. Fred Meeks was a white man. He met Cherokee sometime during the early 1940s. They married at Fort Smith, Arkansas, on December 20, 1945. Together, they had nine childreneight boys and one girlranging in age from eighteen to three at the time of their residency application. Fred and Cherokee clearly hoped to make a new life for their family in Queensland. It was a good choice; Fred had worked for a time as a rancher and as an electrician, and had experience in public servicein Denver, Colorado, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, respectively. Additionally, the family claimed to have financial resources at its disposal, declaring Twenty five Hundred Dollars in Clothing and Ranching equipment, such as Saddles, Fifteen to Twenty Thousand Dollars in Currency, on Arrival. The Meeks family was the kind of immigrants the Commonwealth of Australia wanted.

Still, Australia remained a deeply racist and color-conscious society in the mid 1960s. Its immigration laws reinforced the ideals popularly referred to as the White Australia policy. So why would a woman of Cherokee descenta wife and mother of ninewant to relocate to such a country? Were Fred and Cherokee even aware of Australias racial politics? Probably not; they had no reason to know, or care. Australian immigration officials did care, however. It was their assessment that Fred and Cherokee were white Americans and would assimilate into Australian society. Still, someone thought it important enough to make that notation about Cherokees mother: White, English decent and Quarter Cherokee Indian.

Next page