R ecently, Cherokees reacquired the land believed to be the site of the original mother town. All future Cherokee villages and settlements in the southeast sprang from this town called Keetoowah.

Before the tribe bought it back, the land had been farmed for years. One day the owner said to her husband, Were not going to plant here anymore. This should belong to the Cherokees.

Once Tommy Belt took Robert Conley out to visit the site. Even after being subjected to years of plowing, the temple mound was still visible. Robert says it was an unforgettable and powerful experience to stand there. This is it, Tommy told him. Where we all came from.

Ancient Cherokee Warriors

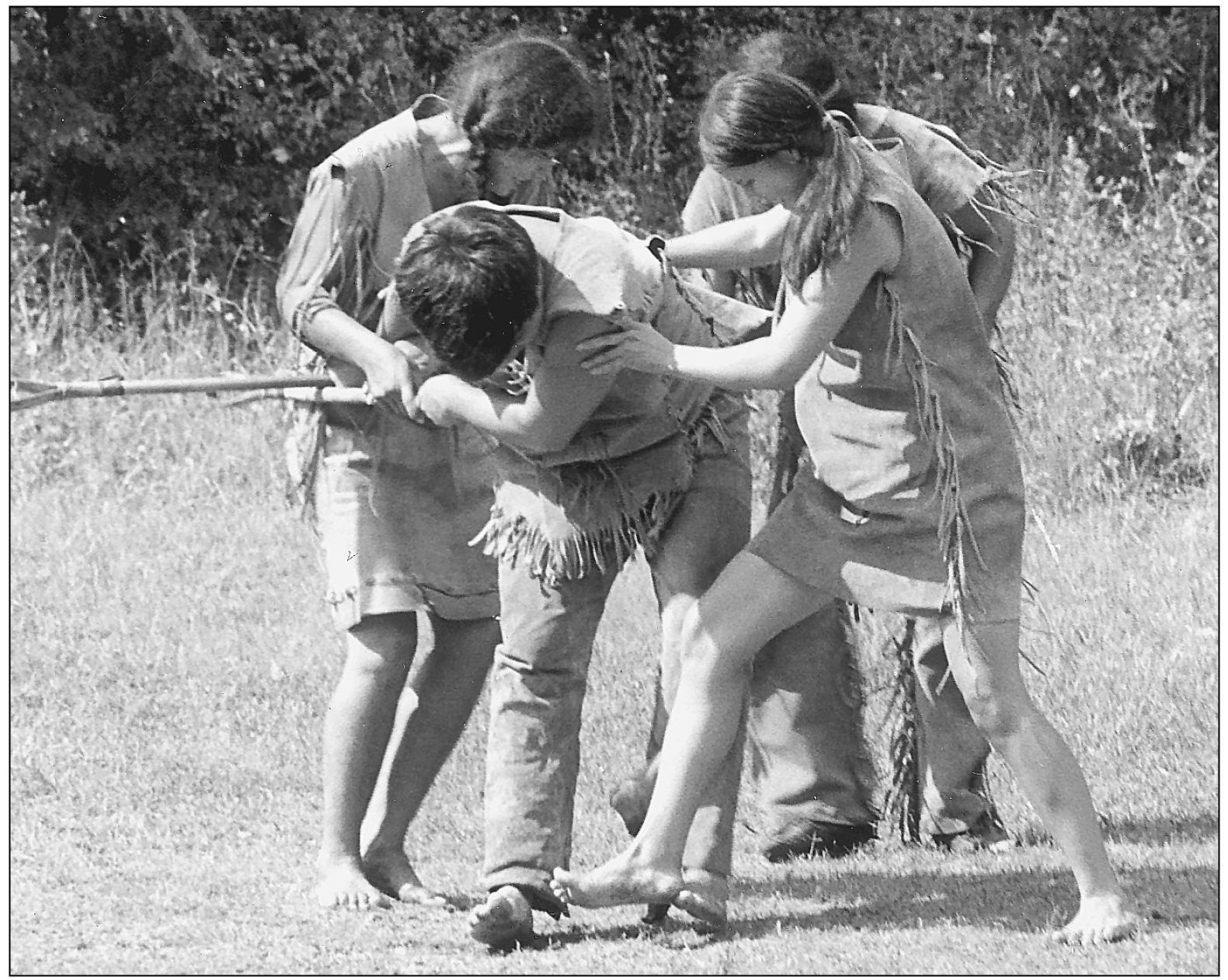

S ince their history began, the early Cherokees were continuously at war with one neighboring tribe or another, particularly the Senecas, Catawbas, Delawares, and Creeks. Likewise, they had allies among their neighbors. The act of war was one of ritual, with established ceremonies and rules of conduct. A favorite pastime for young men in those days was to abduct young women from a neighboring village. Such behavior was almost always answered with a battle, another favorite pastime.

A delegation would be sent to the offending village to issue a challenge of war. A location for the match was selected, and a date and time were set for the meeting. Fighting took place in a clearing fairly close to town so that the wounded could be carried home easily. Villages were not attacked, assuring the safety of the women, children, elders, and their homes.

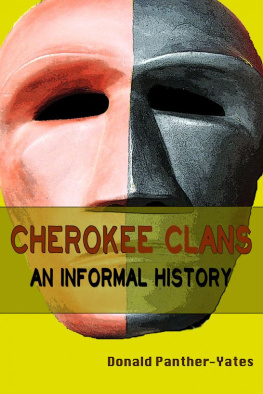

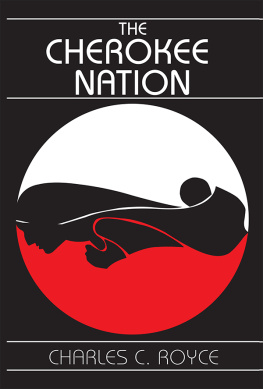

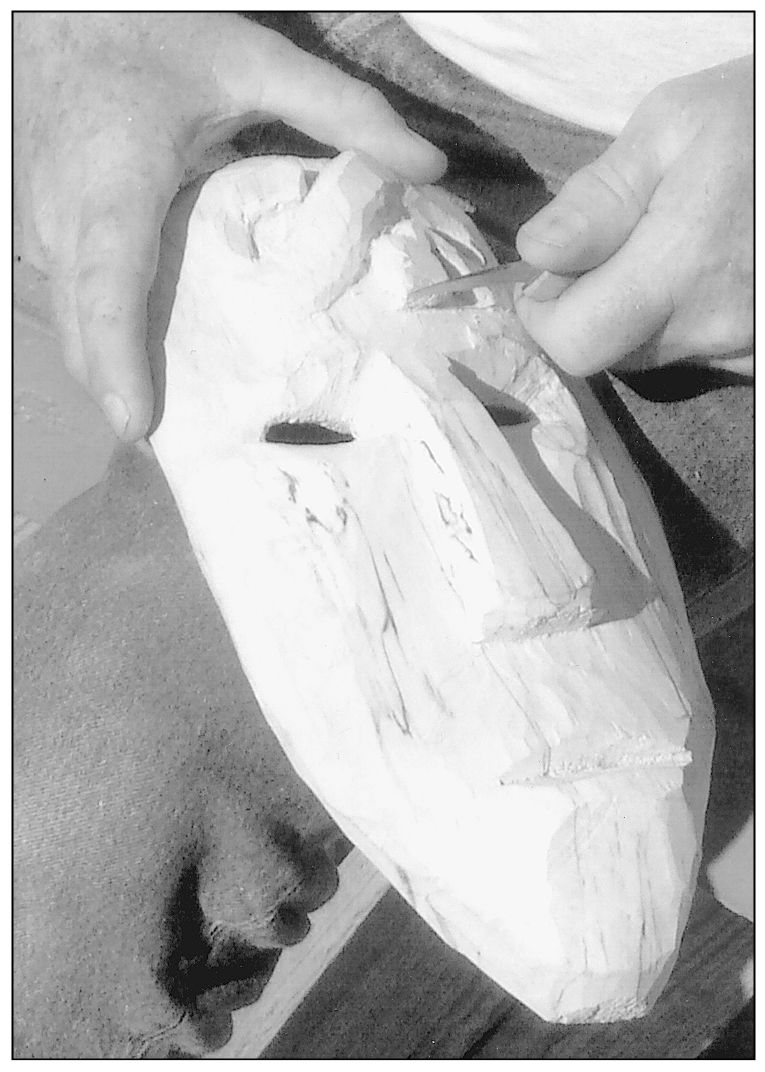

Those who fought in wars relished the experience. Men had a choice of whether to fight or not, and those who did could gain honor and prestige within the tribe. An additional honor was given to the warrior chosen to be the War Dance Leader. Carved into the forehead of the red mask he wore was the emblem of a rattlesnake. He began his dance alone, shaking his rattle around the fire, and those warriors who wished to participate in the fighting joined in.

When the day arrived, the warriors carried their weapons of war, knives and lances made of wood and stone, to the battle ground. Their hunting bows and arrows were of no use to them in hand-to-hand combat. The fighting lasted for a set amount of time, and then it would simply stop. Those killed or wounded were carried home and the battle was over, sometimes with no decisive winner. Victorious or not, the returning warriors celebrated the battle with another big dance and a huge feast. A similar celebration took place in the opposing camp.

Delaware artist and historic researcher Don Secondine states that ancient warriors of his tribe became totally obsessed with the excitement of war. They were constantly going off to fight one tribe or another, until finally the Delaware women decided to put a stop to their antics. The women would find out the location for a proposed battle. When the warriors arrived at the field, they found all their women there, sitting right in the middle of it. After several such protests, the men settled down for a time.

The Cherokees were known throughout the southeast as fierce fighters, and ritualized combat was an essential element of their culture. They continued to perform the Scalp Dance until the early 1800s.

Murv Jacob

The Little Mountain People

I n his Legends and Folklore of the Cherokees, Dub West includes a story of giants who once visited the Cherokees in their southeastern homeland. They came from far away in the direction of the setting sun. The giants were twice as tall as normal people, and their eyes were set in a slant. Cherokees called them the slant-eyed people. They stayed for a time with the Cherokees, where they were treated as friends. Then the giants returned to their home in the West.

War Dance Mask. (Carving by Murv Jacob. Photo by Edison Stinson.)

There was another story of a race of people who were living in the Smokey Mountains when the Cherokees first arrived there. These people were very small, frail, and meek, with pale skin. Migrating birds of a certain kind would come to the mountains once every year and attack the little people. The tribe would see the bird feathers blowing in the wind, and know that they were coming. They would hide from the birds in caves until they went away. The Cherokees felt sorry for the pale people, but were unable to do anything about the birds, which came by the thousands.

After the Cherokees had lived in the area for a few years, the pale people moved away, never to return. The story has come down through many generations that the little people left because they were somehow offended by the Cherokees.