Colin G. Calloway

N. Bruce Duthu

Timothy J. Shannon

John L. Kessell

Brenda J. Child

G ENERAL E DITOR: C OLIN G. C ALLOWAY

Advisory Board: Brenda J. Child, Philip J. Deloria, Frederick E. Hoxie

THE CHEROKEE NATION AND THE TRAIL OF TEARS

THEDA PERDUE AND MICHAEL D. GREEN

THE PENGUIN LIBRARY

OF AMERICAN INDIAN HISTORY

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2007 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, 2007

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Perdue, Theda.

The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears / Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green.

p. cm.--(Penguin library of American Indian history)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0234-0

1. Cherokee IndiansHistory19th century. 2. Cherokee IndiansRelocation. 3. Trail of Tears, 1838. I. Green, Michael D., 1941-II. Title.

E99. C5P3933 2007

975. 004'97557--dc22 2006036092

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

For Mary Young and Ray Fogelson

CONTENTS

THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE

CIVILIZING THE CHEROKEES

INDIAN REMOVAL POLICY

RESISTING REMOVAL

THE TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA

THE TRAIL OF TEARS

REBUILDING IN THE WEST

INTRODUCTION

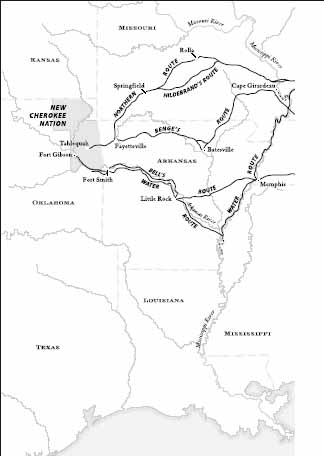

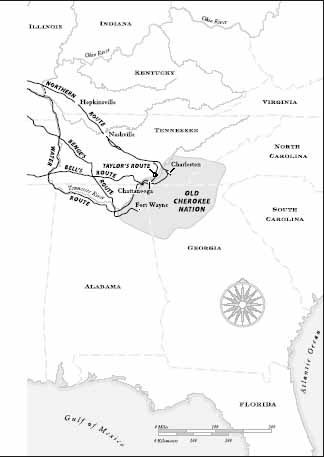

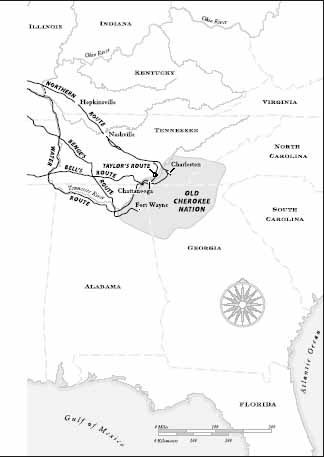

ALL CHEROKEES ONCE lived in the southern Appalachians. In the eighteenth century, they claimed hunting grounds that extended into Kentucky, but they clustered their villages and agricultural fields in the valleys of upcountry South Carolina, western North Carolina, east Tennessee, north Georgia, and northeastern Alabama. They spoke four mutually intelligible dialects of an Iroquoian language. A common culture and bonds of kinship held their far-flung villages together and made them a people. Today, most Cherokees do not live in the Southeast; they live in eastern Oklahoma with only a small remnant remaining in the mountains of western North Carolina. The United States recognizes three tribesthe Cherokee Nation and United Keetoowah Band in Oklahoma and the Eastern Band of Cherokees in North Carolina. The division of the Cherokees was not by choice. In the early nineteenth century, the United States forced the Cherokee Nation to surrender its homeland and relocate west of the Mississippi. That event, known as the Trail of Tears, is the subject of this book.

The term Trail of Tears, a rough translation of the Cherokee nunna dual tsuny , describes the trek of heartbroken people to their new homes in the West. The term captures the essence of the removal experience, but it also conveys the impression that removal was a uniquely Cherokee experience. Although that was not the case, there are reasons why scholars have so frequently told the story of Indian removal in Cherokee terms. One is that the debate over removal policy that occurred in the press, various public settings, and Congress focused on the Cherokees. The laws, treaties, and historical examples cited as the discussions progressed always related to the Cherokees. To many, the Cherokees demonstrated that Indians could change and that someday they could be integrated into American society. Furthermore, the Cherokee leaders during the removal crisis of the 1820s and 1830s were uniquely well educated and extraordinarily articulate in both spoken and written English. In countless public speeches and written statements, they produced a trove of documents that dwarfs the records of other Native nations. They were also masters of public relations. Their policy was to make certain that no one could forget them. The result is that the Cherokees have become the Indians whose name everyone knows, and the history of their suffering has come to represent the injustice that has characterized much of the relations between the United States and Native Americans. Only about 10 percent of the eastern Indians who traveled trails of tears to the place now called Oklahoma were Cherokees, however, and each of the dozens of relocated tribes has its own unique and important history. The history of the removal of the Cherokees can never substitute for the histories of the others, but it can exemplify a larger history that no one should forget.

The period in which Indian removal unfolded was one of contradictions. It was hailed by an earlier generation of historians as a period of expanding democratic institutions, but more recent scholars have pointed to the limitations on that democracy. In the early nineteenth century, states largely abolished property restrictions on voting and made it possible for all adult white men to exercise the franchise. At the same time, legislatures further limited the rights of women and free African Americans, and southern states enacted far more stringent slave codes. Legislation increased the number of offices filled by election, but the spoils system enabled the victors in elections to reward their political cronies with positions, contracts, and other perquisites of power. The wave of revivalism that began at the turn of the century brought more Americans into churches, but it created a split between those who believed in the perfectibility of society and those who focused on individual salvation. Southerners, in particular, tended to worry about their own souls and suspect those who dwelled on social ills. A market revolution both tied rural folk to national issues and left many of them in an economic backwater. The West was the land of promise to thousands of Americans, but its settlement by citizens of the United States spelled disaster for the Native peoples who already lived there. No one better understood the contradictions of this age of democracy than the Cherokees, who adopted many of its institutions only to suffer from the tyranny of the majority and who rejected whatever opportunities the West offered only to be forced there against their will.