VOICES FROM THE TRAIL OF TEARS

Published by John F. Blair, Publisher

Copyright 2003 by Vicki Rozema

All rights reserved under International and

Pan American Copyright Conventions

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

for permanence and durability of the

Committee on Production Guidelines for

Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources

Image on front cover

Relocation Arlene White

(Mohave Tribe)

http://earthrunner.com/4wings

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Voices from the Trail of Tears / edited by Vicki Rozema.

p. cm. (Real voices, real history series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-89587-271-4 (alk. paper)

1. Trail of Tears, 1838. 2. Cherokee IndiansRelocation. 3. Cherokee IndiansHistorySources. 4. Cherokee IndiansGovernment relations. 5. Indians, Treatment ofUnited StatesHistory19th century. 6. United States. Act to Provide for an Exchange of Lands with the Indians Residing in any of the States or Territories, and for Their Removal West of the River Mississippi. 7. United StatesPolitics and government1815-1861Sources. 8. Jackson, Andrew, 1767-1845Relations with Indians. I. Rozema, Vicki, 1954- II. Series.

E99.C5 .V65 2003

973.049755dc21 2002015299

Book design by Debra Long Hampton

Composition by The Roberts Group

For my brother and his family, Michael, Donna, Stacy, and Sam Bell

CONTENTS

GROWING UP AROUND CHATTANOOGA, I was vaguely aware that the Trail of Tears passed through this area. Like many Southerners, I heard stories of groups of Indians camped on someones land or traveling along some old road nearby as they slowly and tragically made their way west. My own family had a story about the removal. My great-great-great-grandmother had avoided the Trail of Tears by marrying a white man, my great-great-great-grandfather. After some research, I now believe they may have met while he was serving in the Alabama militia during the Cherokee Removal.

Although Southerners have heard of the Trail of Tears, most are unaware of the whole story of the removal of the Cherokees or the magnitude of the effort. As a child, I had no idea that the hospital where I was born overlooked the site of a large removal camp located in what is now East Chattanooga. I was unaware that the church I attended in the Brainerd area was located on one of the main removal routes to Rosss Landing. Nor was I aware that one or two thousand Creeks, black slaves, and Cherokees were marched right by the site of the church to the Tennessee River. I lived on Old Harrison Pike for ten years without knowing it was the route used by a detachment of over a thousand Cherokees who crossed the river just north of my home.

Few Chattanoogans are aware that what is now Hamilton County was a bustling center of activity from 1836 to 1838, as United States armed forces, local militia, government emissaries, enrollment agents, physicians, interpreters, supply experts, speculators, and wagon drivers descended on the area in preparation for the huge logistical effort of collecting and feeding the Cherokees prior to transporting them west. And of course, thousands of Cherokees stopped in Chattanooga to enroll for emigration, stopped at the Brainerd Mission on their way to the Red Clay Council meetings, settled here in temporary makeshift quarters after being forced from their homes in Georgia, marched through the area under the threat of artillery to the boats at Rosss Landing, or camped here during the drought-stricken summer of 1838 waiting for Rosss self-removal emigration. These tragic scenes of organized confusion were repeated elsewhere in northern Alabama, northern Georgia, and western North Carolina, but not on as large a scale as they were in Bradley and Hamilton Counties in Tennessee, where the main removal camps and the two main emigrating depots were located.

It wasnt until a few years ago that I began to understand the magnitude and scope of the removal of the southeastern Indians. Thousands of Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles and remnants of other southeastern tribes had undergone forced removal during the 1820s, 1830s, and early 1840s. The story of their emigration is not as well known but is just as tragic. And to the north, the Fox, Sauk, Winnebago, Potawatami, Wyandot, Delaware, Miami, and other tribes were undergoing various forms of removal farther west.

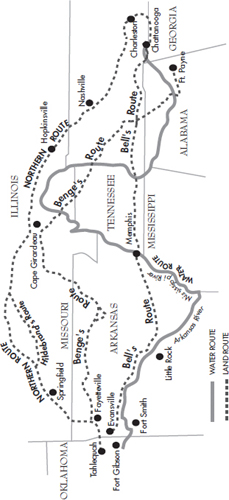

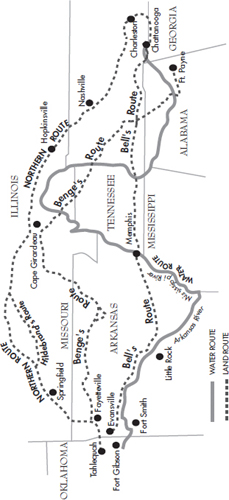

During the removal, Cherokees and thousands of other Native Americans were rounded up at gunpoint, separated from their families, forced into stockades, made to travel on foot, by wagon, and by boat to a foreign land, and compelled to start their lives over virtually from scratch. This is a black mark on American history that must be acknowledged. In 1987, the United States Congress recognized the significance of the Cherokee Trail of Tears by designating it a National Historic Trail. Since 1987, the National Park Service, in cooperation with the National Trail of Tears Association and its state chapters, has been seeking to research, document, certify, preserve, and interpret the routes taken by the emigrants and to identify and protect significant sites along the trail. At present, Congress has recognized only those routes taken by emigrating detachments after June 1, 1838that is, the detachments that left under gunpoint or under John Rosss direction. And congressional legislation thus far has honored only the segments from the main embarkation depots at Guntersville, Chattanooga, and Charleston. But there is an effort under way to ask Congress to officially recognize other sites in other states, including Georgia and North Carolina, that were used during the collection of the Cherokees by including them under the National Historic Trail umbrella.

The exact routes taken by the various detachments are not known at this time. For several years, members of the National Trail of Tears Association and state chapters have been combining their efforts to identify the exact routes and to document other aspects of the Cherokee Removal. During this exacting process, researchers have been able to prove and disprove old stories of where the Cherokees supposedly camped and what roads they used. While significant progress has been made in documenting the Trail of Tears, more research is needed. It may take several more years to finalize the main routes. This unprecedented grass-roots effort to document and certify segments of the trail has led to new efforts to preserve its sites.

As I write, two organizations in Chattanoogathe Chattanooga Regional History Museum and Audubon Acres, also known as the Elise Chapin Wildlife Sanctuaryare undergoing the final steps to be certified as official interpretive sites on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. Plans are also being finalized for the new Cherokee Memorial, to be located in Meigs County at Blythes Ferry, where hundreds of Cherokees camped on the Trail of Tears and thousands crossed the Tennessee River. Efforts are also under way to protect a segment of the Trail of Tears across Moccasin Bend in North Chattanooga as part of the proposed Moccasin Bend National Historic Park. And finally, Vicky Karhu of the Chattanooga Indigenous Resource Center and Library and local members of the Tennessee Trail of Tears Associationespecially Doris Tate Trevino, Shirley Lawrence, Carlos Wilson, Bill and Agnes Jones, and, to a lesser degree, myselfhave worked with the National Park Serviceespecially Steve Burns and Aaron Mahrto identify sites near Rosss Landing and on the north shore so they may be preserved during the impending development of the Chattanooga river front. Recently, their efforts have resulted in planners agreeing to incorporate a new Trail of Tears Memorial at Rosss Landing and agreeing to work with the National Park Service for development of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail in Chattanooga.

Next page