ALSO BY STEVE INSKEEP

Jacksonland:President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab

Instant City:Life and Death in Karachi

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2020 by Steve Inskeep

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Inskeep, Steve, author.

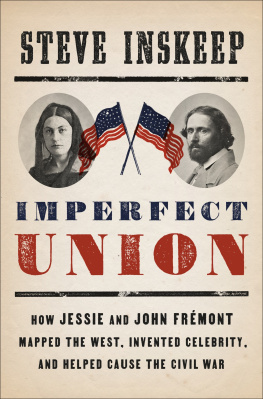

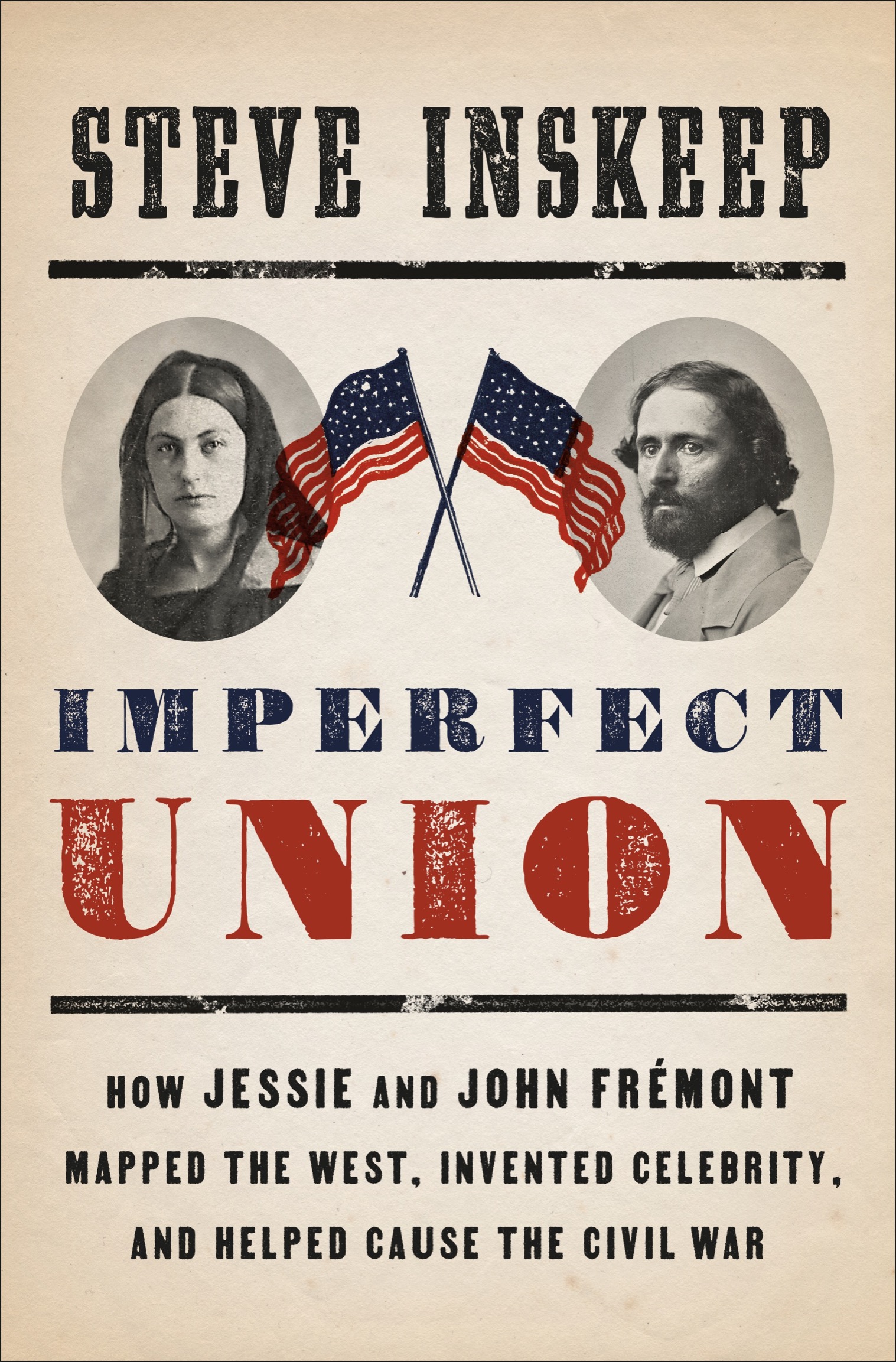

Title: Imperfect union : how Jessie and John Frmont mapped the West, invented celebrity, and helped cause the Civil War / Steve Inskeep.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019030462 (print) | LCCN 2019030463 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735224353 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735224360 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Frmont, Jessie Benton, 18241902. | Frmont, John Charles, 18131890. | ExplorersWest (U.S.)Biography. | Women pioneersWest (U.S.)Biography. | PioneersWest (U.S.)Biography. | PoliticiansUnited StatesBiography. | Politicians spousesUnited StatesBiography. | Womens rightsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Antislavery movementsUnited StatesHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC E415.9.F79 I67 2020 (print) | LCC E415.9.F79 (ebook) | DDC 910.92/2 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019030462

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019030463

Version_1

To all those who make possible my own explorations

Contents

It would hardly do to tell the whole truth about everything.

J ESSIE B ENTON F RMONT

Introduction

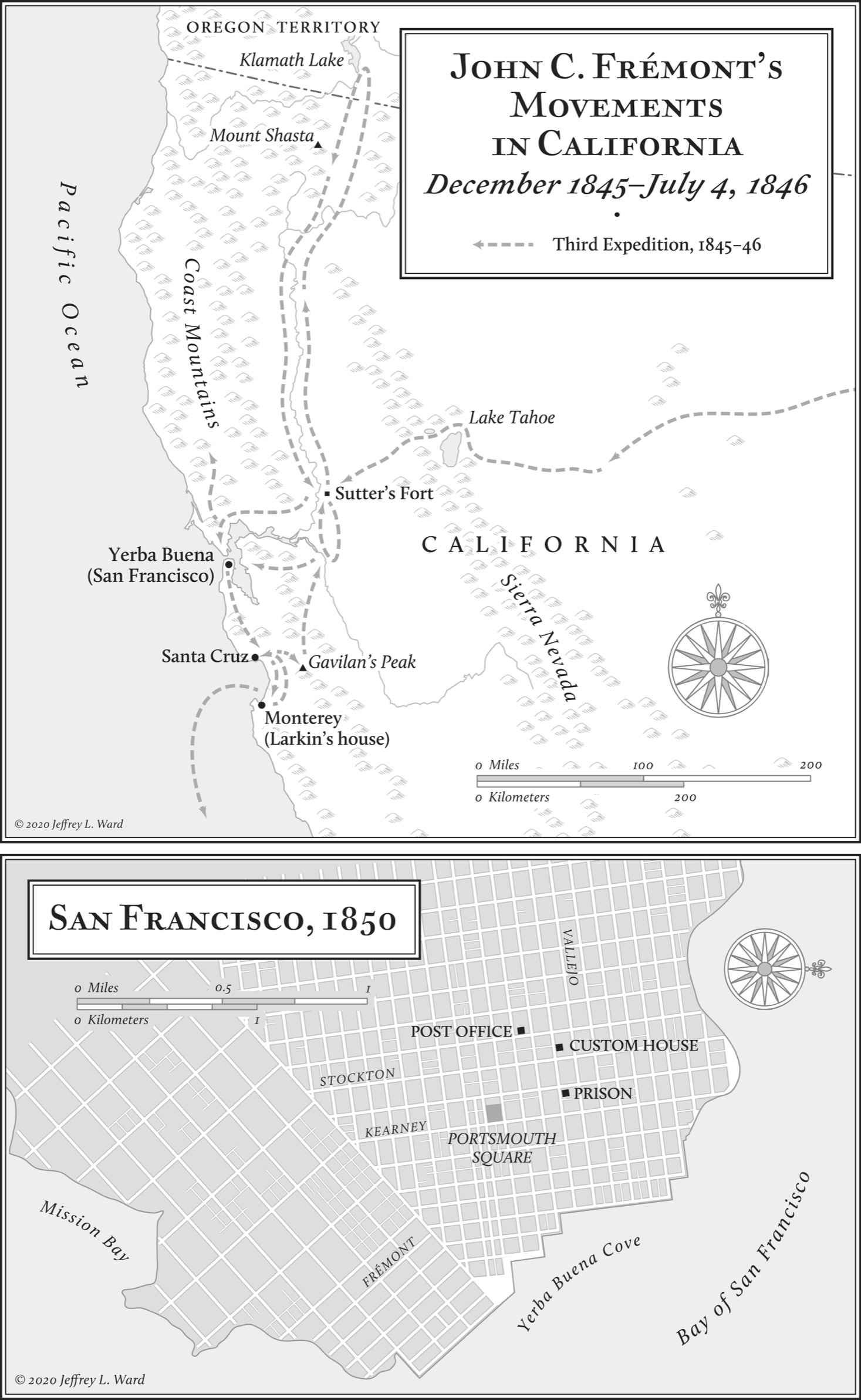

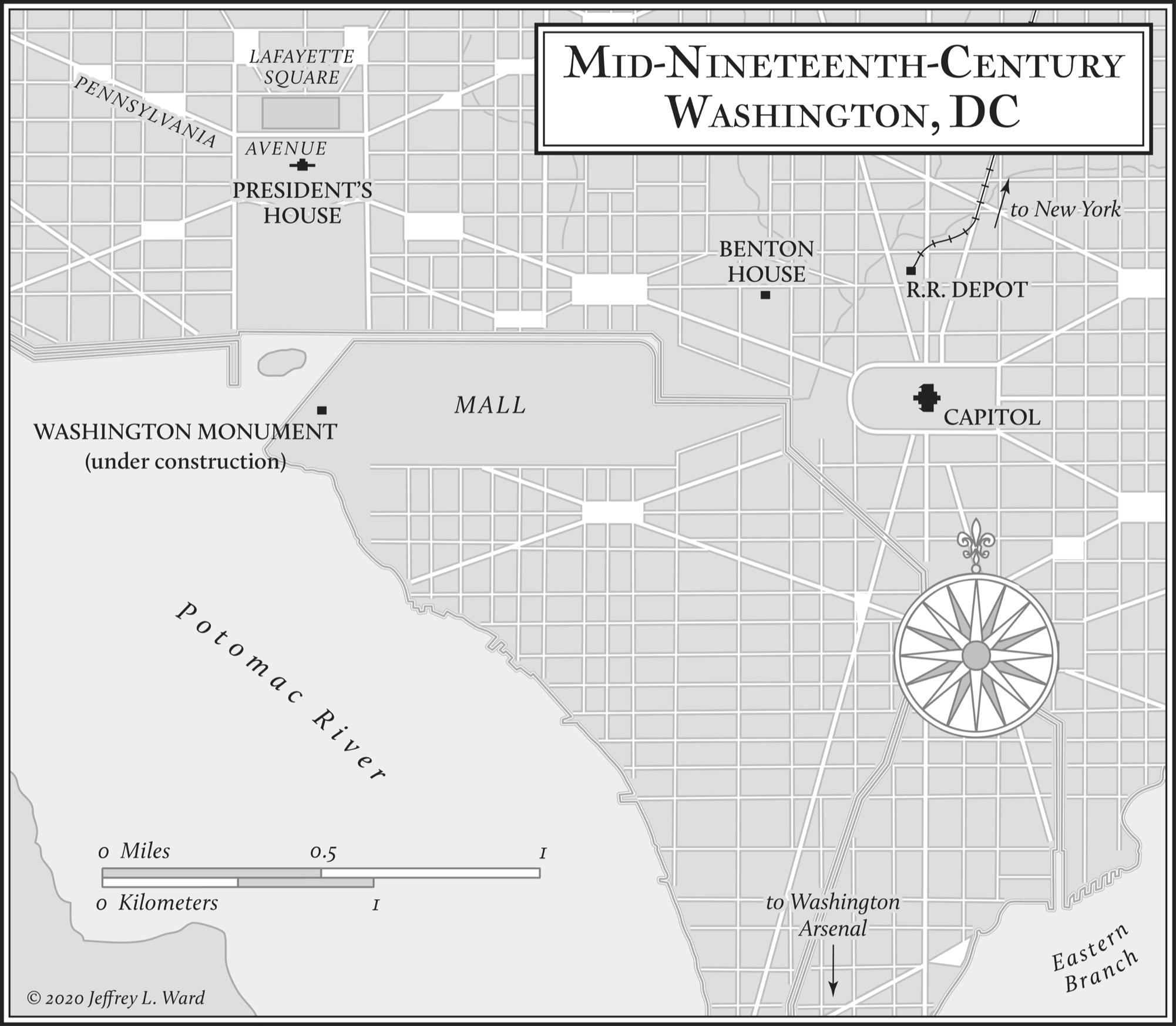

Of the many times John C. Frmont visited St. Louis, the most auspicious came in 1845. He was thirty-two years old, a United States Army captain with shoulder-length hair and a thoughtful expression. Arriving on a steamboat from the east on May 30, he disembarked at the crowded waterfront with two companions: Jacob Dodson, a son of free black house servants from Washington, D.C.; and William Chinook, an Indian from the faraway land called Oregon. It was fitting that Captain Frmont reached St. Louis with men from far to the west and east. His mission was to connect the Atlantic world to the Pacific, surmounting the natural barriers between.

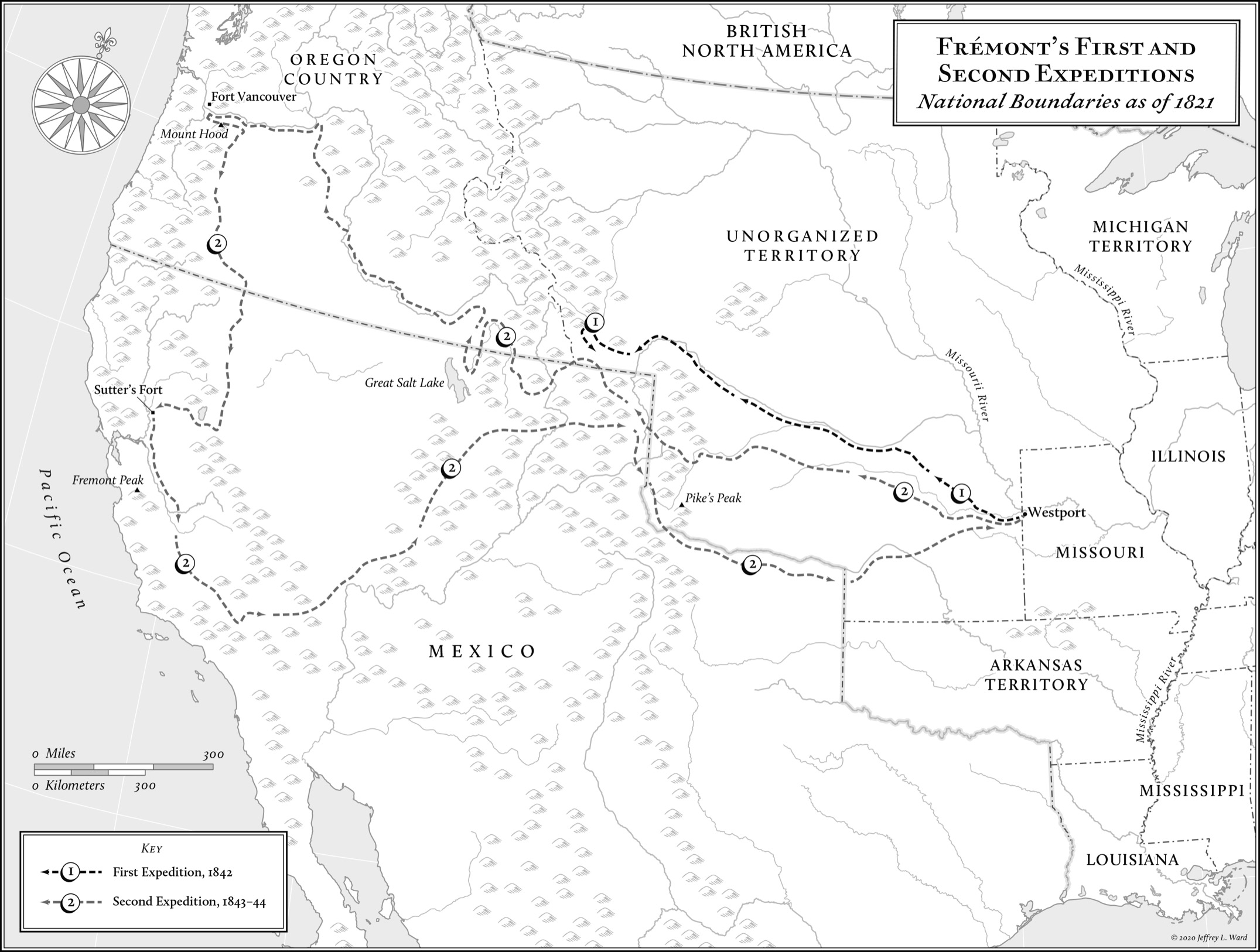

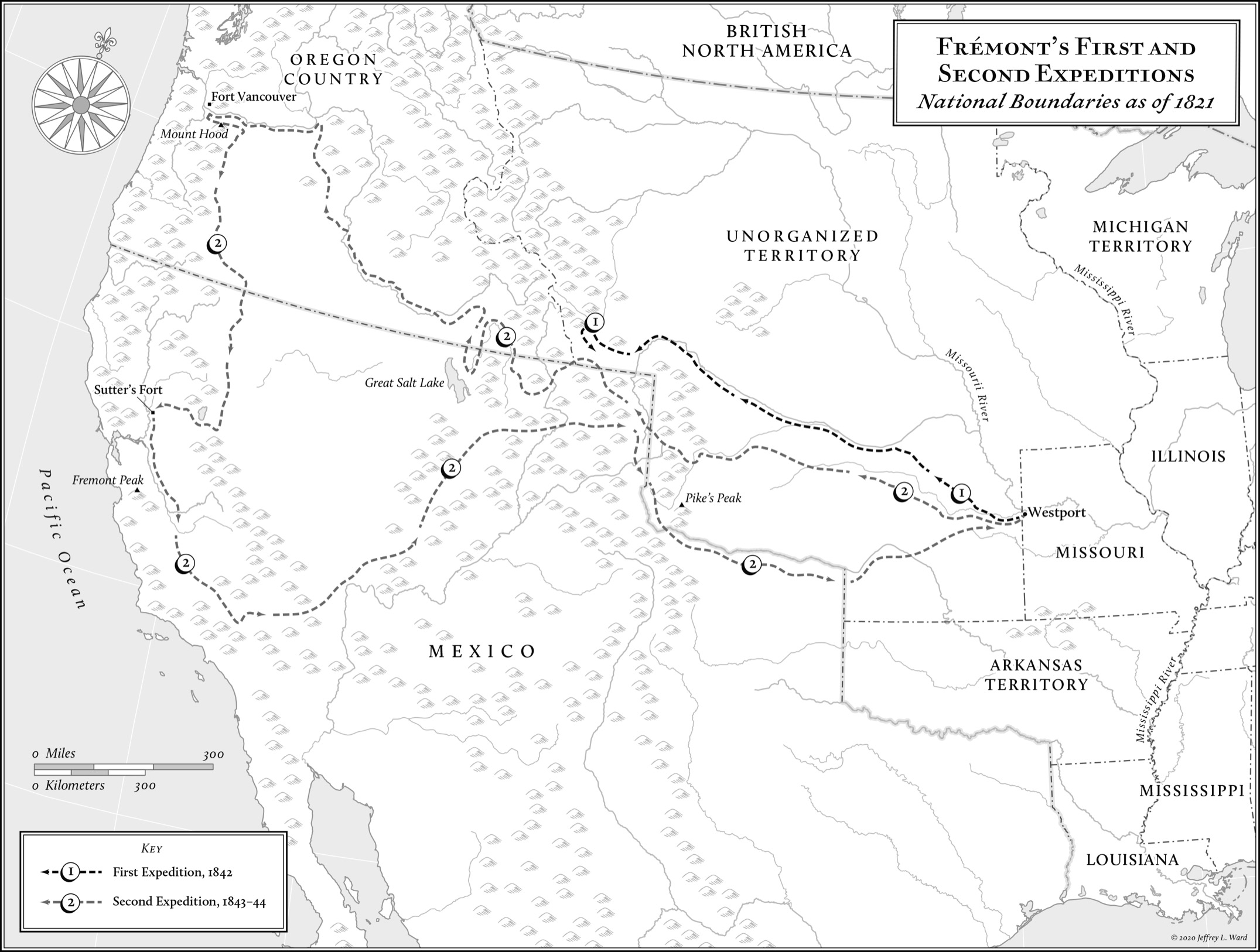

Frmont served in an army unit called the Corps of Topographical Engineers, which had assigned him to draw maps of travel routes through the Louisiana Purchase. Twice in the preceding three years he had recruited small groups of skilled civilians to join him on expeditions that ranged across thousands of miles of prairies, mountains, and deserts. Each time their starting point was St. Louis, the commercial hub of Missouri, which was the westernmost of the United States. Now Frmont was about to command his third expedition, and his preparations in St. Louis should have been routine. He needed to hire men and buy suppliescamping equipment, rifles, food, brandy, and coffee. (The coffee was vital; he had run out once on the prairie, a painful mistake he would never repeat.) But something happened as Captain Frmont made his customary rounds. His arrival was mentioned in a local newspaper, which created an unmanageable situation. James Theodore Talbot, a twenty-year-old aide who joined him in St. Louis, described Frmonts problem in a letter to his mother. He was assailed by people anxious to accompany him on his expedition, Talbot wrote. Wherever he goes he gathers a little train. The job seekers would not let him alone. Declining to stay with Talbot at the Planters House Hotel, where he might be spotted, the captain hid himself in some French house down the City. So many men asked for him at the hotel that a clerk vowed to put up a sign reading, Captain Frmont Did Not Stay Here.

Frmont spread the word that he would meet potential recruits at a warehouse, where he might stand on a barrel packed with tobacco leaves to address them. But when he arrived before ten oclock on the morning of June 2, he found an unruly mass. You ought to have witnessed the scene, Talbot wrote his mother. Long before the appointed hour the house was filled and Capt Frmont found it necessary to adjourn to an open square.... The whole street and the open space was crowded. We could easily trace the Captains motions by the denser nucleus which moved hither and thither. They broke the fences down and the Captain finally used a wagon as a rostrum but it was impossible for him to make himself heard. Men were elbowing each other to reach him, wanting so badly to talk to him that they would not listen. Frmont, too polite and reserved to command the crowd, gave up and fled. But men found where he was staying and chased him even into his bedroom, forcing his free black servant, Jacob Dodson, to use all his strength and vigilance in a vain effort to keep them away. A St. Louis newspaper declared: This is the strongest manifestation of the Oregon fever that we have yet witnessed.

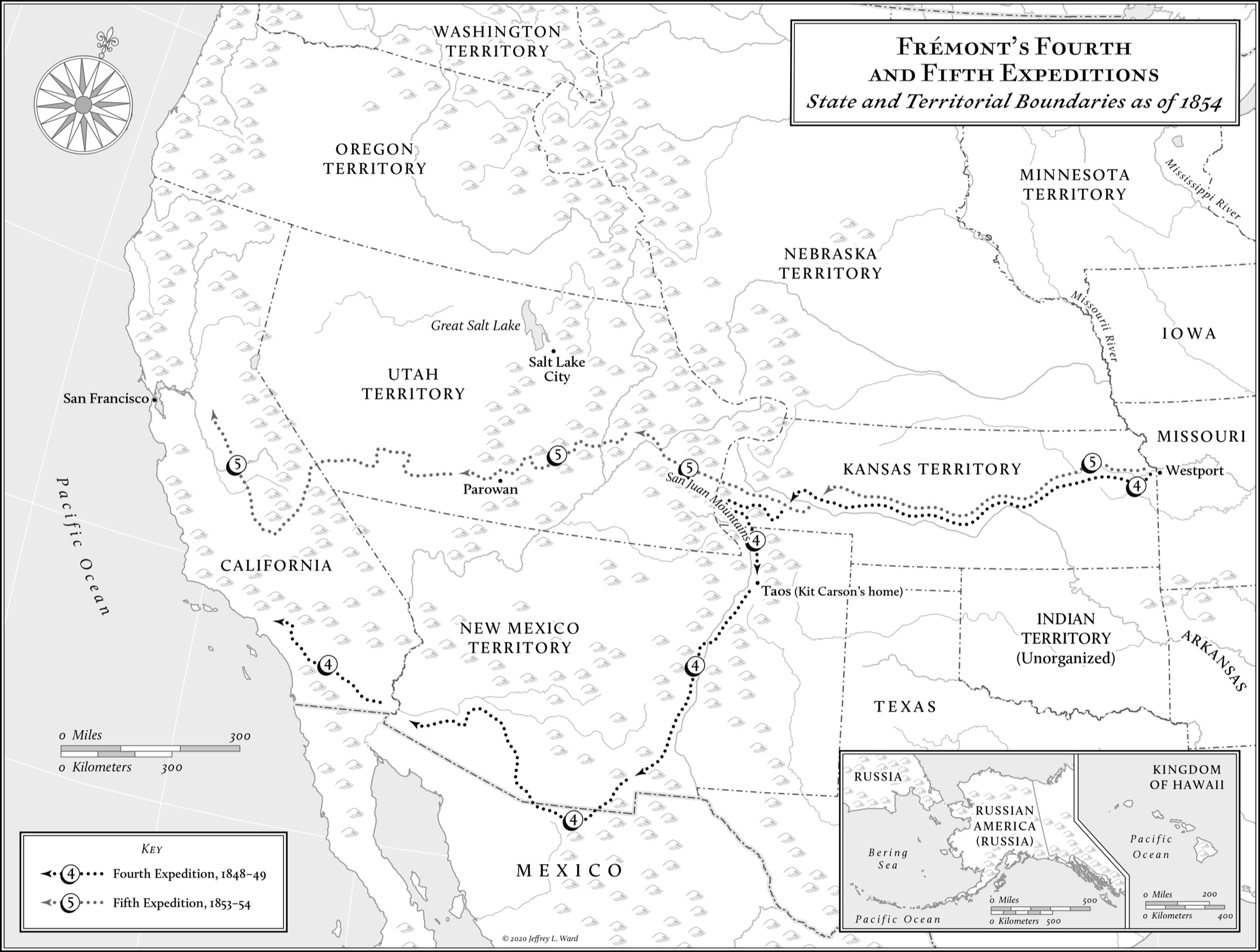

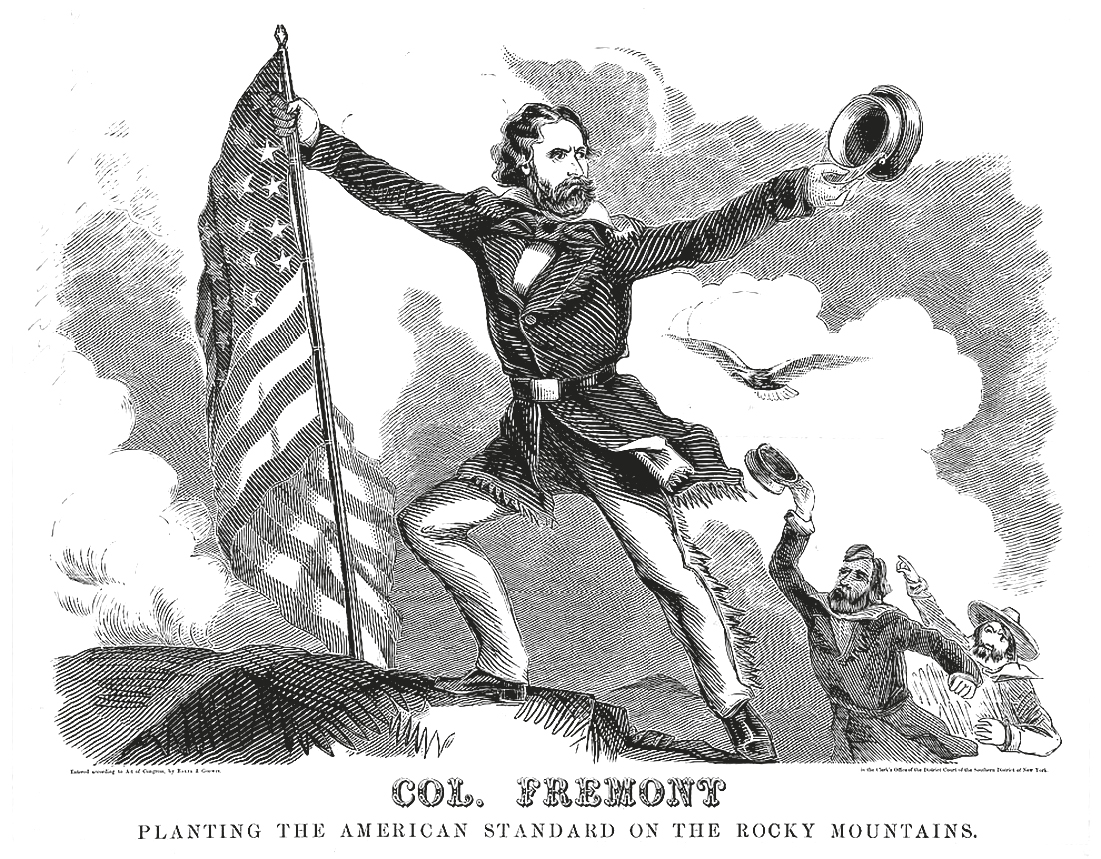

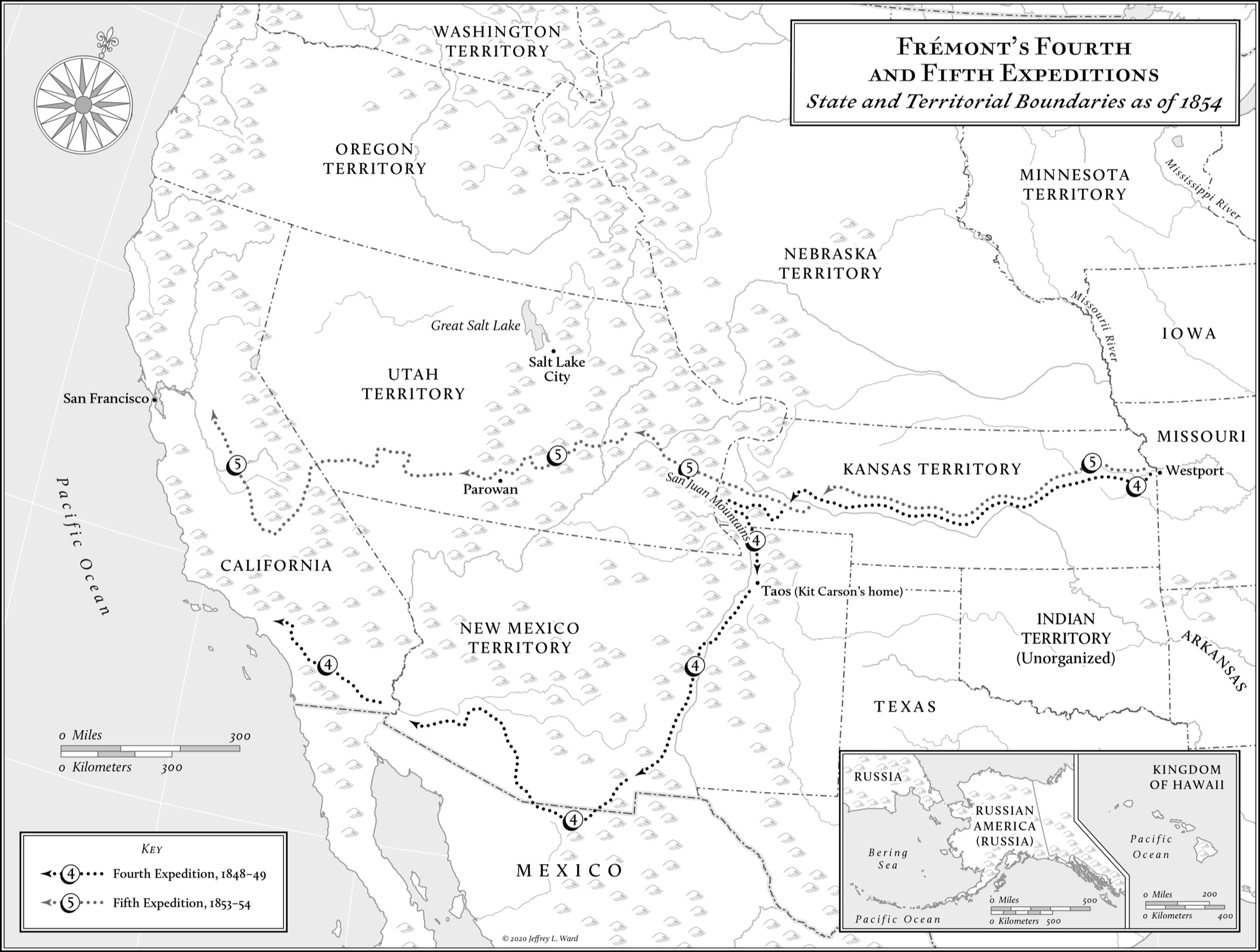

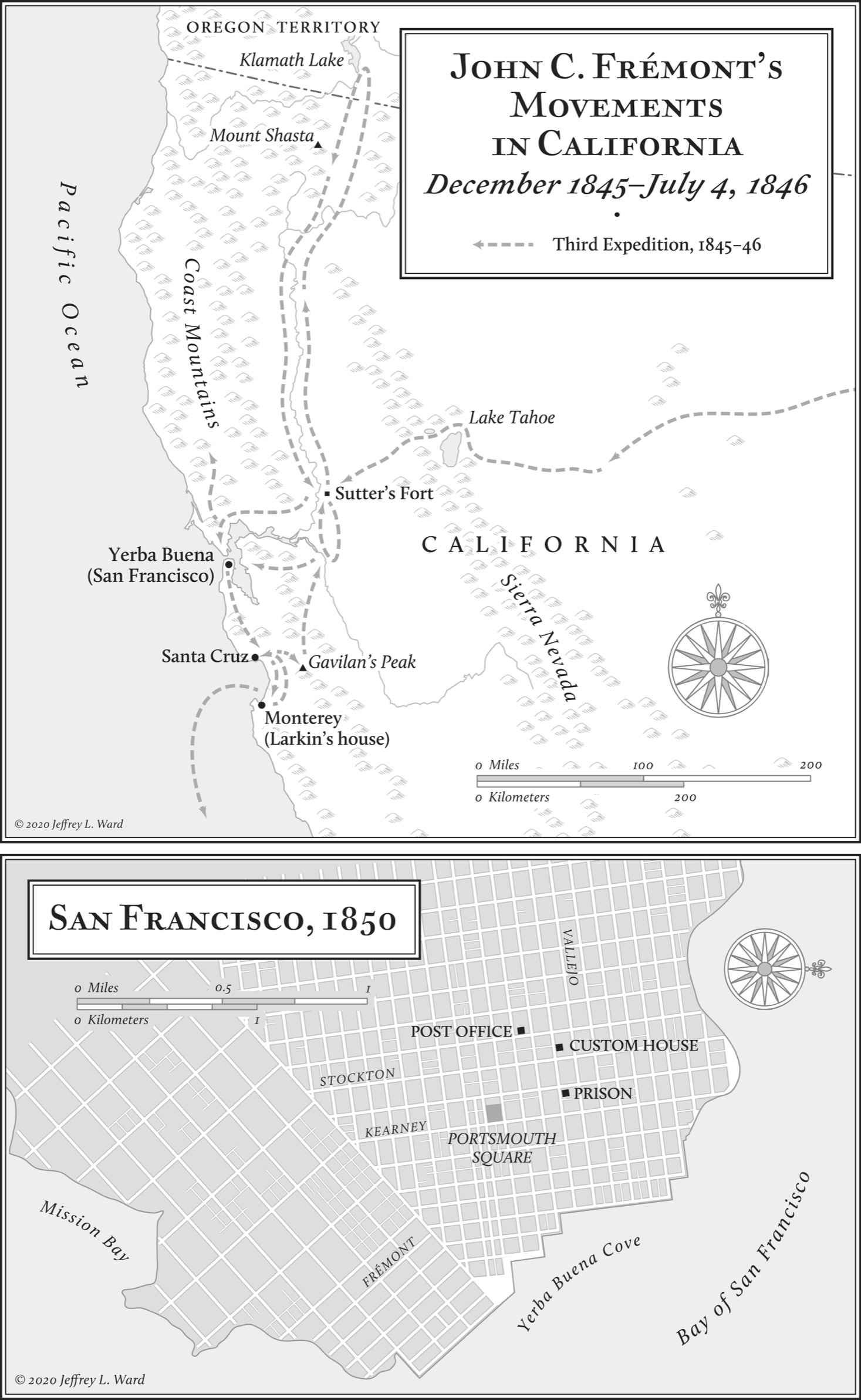

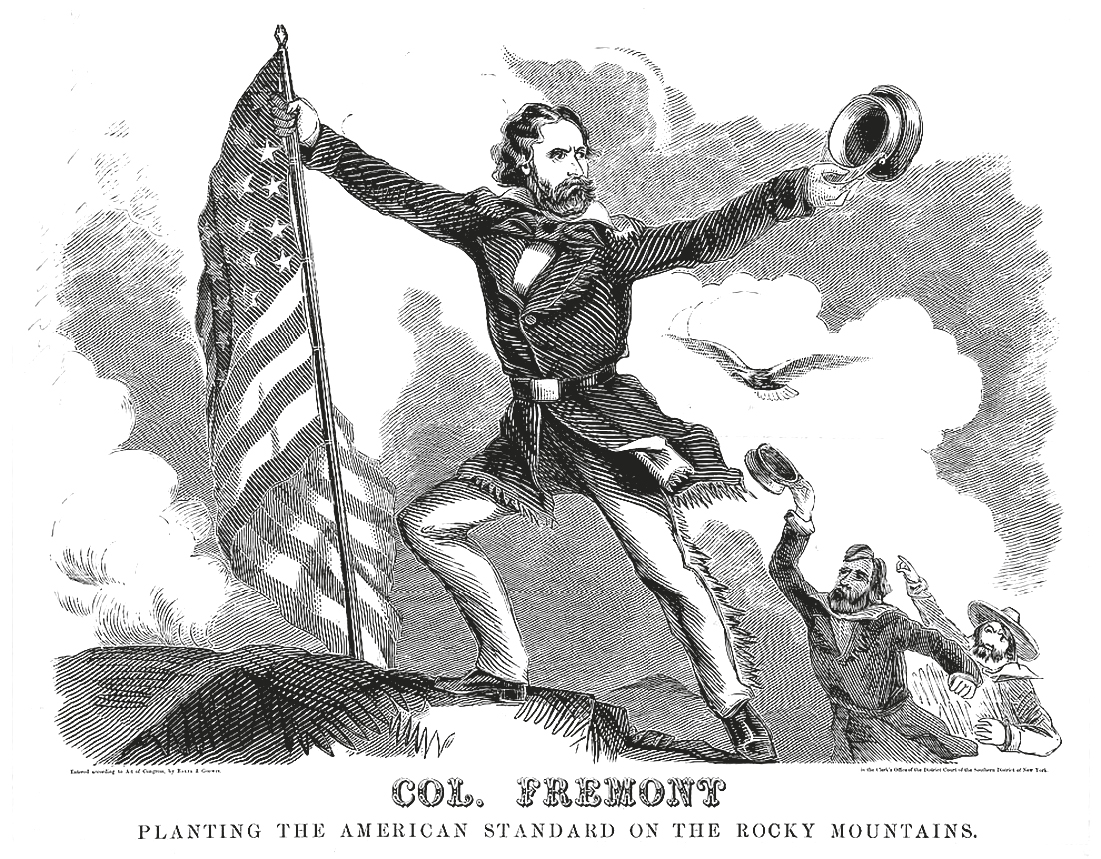

It was one episode in the life of John Charles Frmont, among the most famous men of his time. He had risen from obscurity just since 1842, when he commanded the first of his major expeditions. After traveling for months at a time on horseback and foot, often through deep snow, he went home to Washington, D.C., to write reports to the army about his adventuresand he told his stories so evocatively that his reports were excerpted in newspapers and published as popular books for the general public. His tumultuous arrival in St. Louis in 1845 marked a new phase in his work: the men he recruited that year deliberately rode outside the territory of the United States, crossing the mountains to reach the Pacific coast near San Francisco Bay. There, his sixty armed men helped to trigger the United Statess conquest of the Mexican territory of California. This conquest was not even complete when the once-impoverished young officer began buying many square miles of California real estate, where he afterward struck it rich during the Gold Rush of 1849.

While it was natural that such a life would make him well known, Frmonts fame grew to proportions that were not easily explained; other adventurous people of his era could hardly compare. Newspapers reported his every move. A contemporary journalist called him the Columbus of our central wildernesses, while a magazine in 1850 went further, listing Columbus, Washington, and Frmont as the worlds three most important historical figures since Jesus Christ. He was not even forty years old when Americans began naming mountains and towns after him. Europeans thronged to invest in his gold-mining projects, and followed each step of his adventures: 350,000 people attended a long-running stage show in London that featured paintings of his experiences. His fame made it possible for him to enter politics, lifting him to a seat in the Senate and propelling him in 1856 to become the first-ever presidential nominee of the newly established Republican Party. John C. Frmont was a social and political phenomenon of a kind we associate with modern celebrity culture.