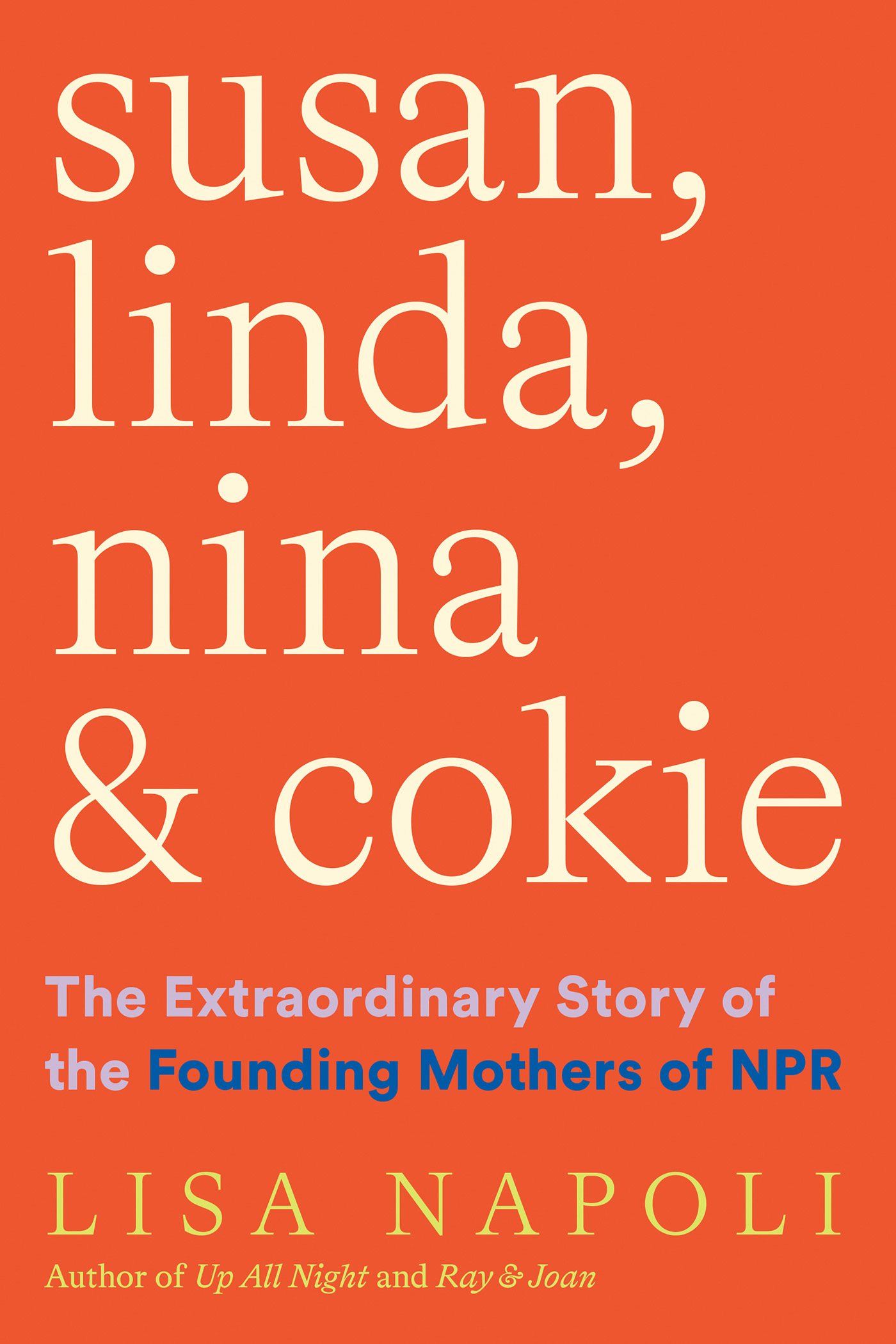

Contents

Guide

Page List

Also by Lisa Napoli

Radio Shangri-La: What I Discovered on My Accidental Journey to the Happiest Kingdom on Earth

Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonalds Fortune and the Woman Who Gave It All Away

Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN, and the Birth of 24-Hour News

Copyright 2021 Lisa Napoli

Cover 2021 Abrams

Published in 2021 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944990

ISBN: 978-1-4197-5040-3

eISBN: 978-1-64700-107-0

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

For Bill Siemering, the founding father Im fortunate to call a friend

For all who work behind the scenes, without public acclaim, in newsrooms everywhere

and

For my mother, Jane, who told me how it used to be and worked so hard for my experience to be different.

Many women may be fine in everyday conversation, but put them in front of a microphoneand a camera as welland something happens to them. They become affected, overdramatic, high-pitched. Some turn sexy and sultry. Others get patronizing and pseudocharming. Not that they all put on an act. But with a man you seldom have this problem.

NBC network radio executive, 1964

Interviewer: How do you feel when you meet younger women in journalism who havent any idea how rough things used to be in the bad old days?

Nina Totenberg: Murder comes to mind.

History looks very different when seen through the eyes of women.

Cokie Roberts

Authors Note

As I write this in October 2020, our world is in a perilous state, even beyond the deadly pandemic that has us in its grip.

For decades, weve ignored dire warnings about our environmental destructionnote that Earth Day was launched back in 1970 to call urgent attention to our dwindling resources. Similarly, society has dismissed or minimized the issue of what today we call diversity and inclusion.

To serve those whose needs were woefully underrepresented by commercial broadcasting, National Public Radio was chartered, coincidentally, also in 1970. Later that decade, a task force concluded after an eighteen-month review that, on the air and behind the scenes in public radio and television, minorities remained nonentities who were still drinking from segregated water fountains. A detailed report called for immediate change.

Today, at the network level at least, there has been a slight increase in the number of employees of color and other marginalized groups. But, on the national and local levels, public radio (indeed, all of the fourth estate, as news media are called) faces a vocal reckoning from a new generation: Address this shameful inequity once and for all.

From its beginnings, public radio did, in one arena, a slightly better job of addressing the needs of a constituency that, at the time, also was rarely given a voice: women. This is the story of how that happened, quite by accidentand how a man almost did the place in.

Lisa Napoli, Downtown Los Angeles, October 2020

. The task force was chaired by Dr. Gloria L. Anderson, whose appointment to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting by President Nixon in 1972 made her the first Black woman to serve on that board.

A 2019 study showed that women comprised 57 percent of NPRs staff.

PROLOGUE Living Legend

On August 18, 2019, Mary Martha Corinne Morrison Claiborne Boggs Roberts, age seventy-five, did what shed done for thousands of Sundays. She left her beloved home on Bradley Boulevard in Bethesda, Marylandthe magical, Gone with the Windstyle property shed begged her parents to buy nearly seventy years before, where she slept each night in the antique cherrywood rope bed that had been in her family for generationsand made her way to the studios of ABC News in Washington, DC.

Her manicured nails polished fire-engine red and her short hair neatly styled to perfection, the womannicknamed Cokie as a child due to her brothers inability to pronounce Corinnehad learned to enjoy that pampering necessity of television, a turn in the makeup chair. Cosmetic flourishes, like chopping off her long, straight gym teacher hair into a more glamorous do when she transitioned from radio to TV, were part of the job. Celebrity came with many perkslike a better table at a restaurant and gratis wine from starstruck flight attendants, if they hadnt already upgraded her to first class. It also meant being on display on a run to the grocery store.

Glamour wasnt what attracted the audience to Cokie. The adulation was sparked by the fact that she seemed like a woman in your book club, someone you ran into at the local farmers market who remembered your husbands recent surgery, or your daughters recitala PTA mom consumed with her own family, canning tomatoes from her garden, rushing to church on Sunday morning.

Except that Cokie rushed to church after appearing on national television, where it was her job to break down inside-the-Beltway shenanigans for a rapt audience of millions as if she were dissecting a football game with the guys at the local bar. Except that Cokie knew the inner workings of Washington so intimately that she tutored newly elected lawmakers in its history and protocol. Cokie, unlike anyone else you knew, was on a first-name basis with the power elite. She happened to be one of them herself.

Yes, Cokie might have looked like a prettier version of your average neighbor, but there was no one else like her on earth.

This August Sunday, she joined what the producers called a power roundtable of commentators on the long-standing program she once cohosted, This Week. She was emeritus now. Back in 1988, the show had boldly added a skirt, hers, to the boys club cast of characters flanking the original host, David Brinkley, the wry raconteur from her parents generation, whose career arc spanned the evolution of broadcast news. A North Carolinian by birth, Brinkley first made a name for himself in radio, when World War II instructed Americans in the value of what was then the ascendant medium.

Back then, Washington was infinitely simpler; the burgeoning city was so relaxed, went the stories, that a motorist on Pennsylvania Avenue could drive right up to the portico at the White House and turn around. Media, then, were infinitely simpler, too; covering the White House was a part-time beat. When one of the first studio cameras was wheeled into the newsroom, Brinkley and his colleagues demanded to know, What in the hell are we supposed to do with that? As broadcasters struggled to redefine news with pictures, Brinkley morphed and changed and rose to stardom in TV, tooone of a handful of the mediums plentiful lot of patrician white men so elevated. As homogenous as their makeup was their belief system: None of us had any ax to grind; none of us had any political ambitions. Our only real purpose in life, and in work, was to tell people what we knew to be true.