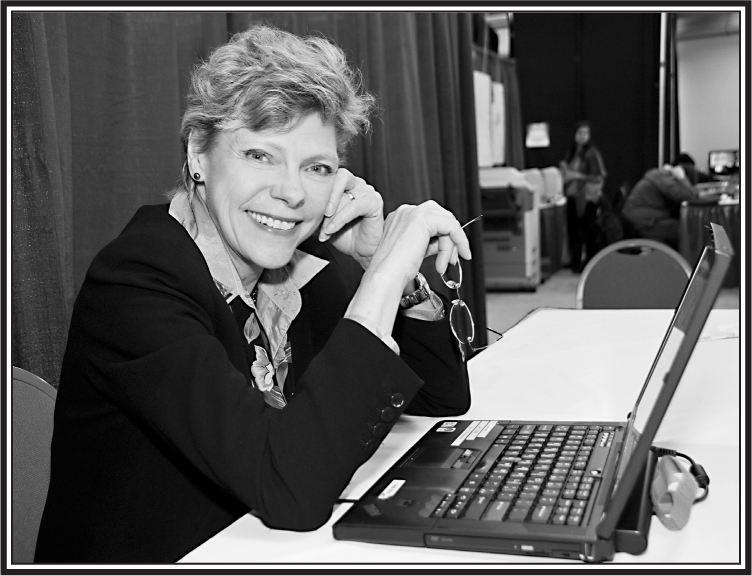

Donna Svennevik/ ABC/Getty Images

C okie died on September 17, 2019, a week after we celebrated our 53rd wedding anniversary. When I gave a eulogy at her funeral in the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in downtown Washington, my aim was simply to tell storiessome funny, some poignant, all personalto illustrate her truly remarkable life. There were a thousand mourners in the church that morning, but countless others heard the ceremony on TV, and the reactions I received were overwhelming. People were hungry for more stories about herher origins and her impact, her generosity and her goodness. So thats why I decided to write this book.

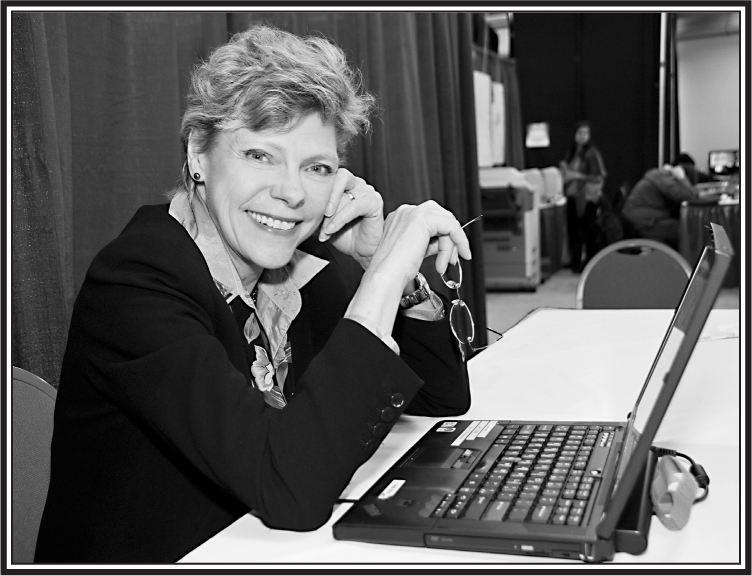

Cokie lived much of her life in public, by the accident of her birth and the choice of her career. Her parents, Hale and Lindy Boggs, both served in Congress, representing the city of New Orleans for a total of almost fifty years. The Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, was a frequent dinner guest during her childhood in the 1950s (in the home I still live in), and President and Mrs. Johnson came to our wedding in 1966 (in the garden of that home). Many obituaries referred to her as the ultimate Washington insider, even as Washington royalty, but her professional success flowed from her own tenacity and talent, not family connections. She wasnt a full-time journalist until she was thirty-four years old, but she made up for lost time, crashing through glass ceilings at NPR and ABC with her impressive mind, impish wit, and infectious laugh. The laugh, wrote Lears magazine, distinguishes her from the self-important chin-tuggers of her trade, makes her someone people connect with. She loved hearing from young women who had followed her on the radio or watched her on TV or heard her at their school and said to themselves, I can be Cokie Roberts. I can be that smart, that confident, that powerful. Diane Sawyer, a colleague at ABC and a fellow graduate of Wellesley, once said, She made you brave.

In another way, however, she wasnt royalty at all. She was accessible and approachable, a suburban housewife, as she often called herself, or an everywoman, as she told Lears: People think Im sort of sensible and like them and go to the grocery store and worry about tuition. But every woman didnt have her propensity for puncturing pomposityespecially if it came from a man, as it usually did. Me included. Her ability to call foul on something that didnt make sense, it just endeared her to people, said ABC executive Bob Murphy. David Westin, who headed ABC News during much of Cokies tenure there, put it this way: She was just Cokie. She knew the stuff, she knew the material, she knew it better than everyone else. And she would tell you what she knew. But she also had, and it sounds lofty, a moral compass to her about right and wrong that she brought to her reporting that stopped short of moralizing. George Will, who shared ABCs Sunday-morning program with her for many years, mentioned Roone Arledge, who preceded Westin as head of ABC News and originally hired Cokie: Roone had this genius for understanding what felt good to viewers. And Cokie felt good. She just brought an ease and confidence and comfortableness. One of the things Roone understood was that television has you in strangers living rooms. So you better not make them uneasy. And Cokie was a good guest in a strangers living room.

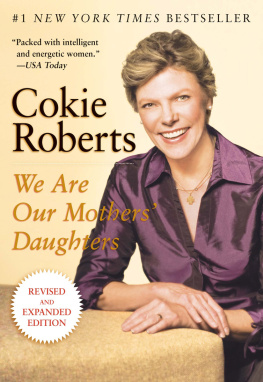

Then in midlife she became a storyteller, publishing her first book at age fifty-four: We Are Our Mothers Daughters, which reached number one on the New York Times bestseller list. Four other bestsellers followed (five if you include a childrens version of one history book), all of which focused on researching and resurrecting the contributions women have always made to American history, while seldom getting the recognition they deserve. As Catherine Allgor, head of the Massachusetts Historical Society, told me, The biggest thing that she did was let Americans know there was a history out there they werent aware of. That just made a huge difference.

Theres one story that sums up what those books were all about. In Founding Mothers, which focuses on the Revolutionary period, Cokie writes about the enormous contribution Martha Washington made to the American cause, spending winters in camp with the soldiers and bolstering their spirits. And it really bothered her that the sign outside of Mt. Vernon, down the Potomac River from the capital, read HOME OF GEORGE WASHINGTON , with no mention of Martha. As Mary Thompson, a historian at Mt. Vernon, tells the tale, Cokie relentlessly pestered the director of the site to change the sign. Thompson usually drove into the grounds on a back road but one day happened to pass through the front gate, and saw that the sign had been altered to read, HOME OF GEORGE AND MARTHA WASHINGTON . Her reaction was to shout, Yay, Cokie! because Im sure that was her doing.

Politics is our family business, Cokie once told People magazine, and if anything, that was an understatement. Her first ancestor to serve in Congress was W. C. C. Claiborne, elected to the House from Tennessee in 1797 at the age of twenty-threethe youngest federal lawmaker in the countrys entire history. So her parents were part of a long and well-established tradition. Author Steve Hess counted eleven Claibornes (Cokies middle name and her mothers maiden name) in major public office over seven generations and rated her family as the second most prominent in American political history, outranking the Kennedys and trailing only the Roosevelts, because they had two presidents. She really became a journalist by accident, mainly because she married one. When a Washington Post reporter asked her, Did you consider entering politics yourself? she gave this revealing answer: Well, I certainly admire people who do it. But Steve and I met when we were 18 and 19. He was always going to be a journalist from the time he was, like, 9 or 10 years old. So, it would have been very hard on him if I had gone into politics. I have always felt semi-guilty about it. But Ive sort of assuaged my guilt by writing about it and feeling like Im educating people about the government and how to be good voters and good citizens. And thats been true through my reporting, but also through writing these history books. I feel like letting people know what this country is all about and how it all happened is not not public service. [Laughs.]

Reporting the news and writing history, however, didnt fully erase her guilt. She wanted more latitude to espouse the causes she felt deeply about, and in 2002, at age fifty-eight, she quit her full-time job as coanchor of ABCs Sunday show This Week. While she had many reasons for doing that, one of the most important was freeing her up to spend more time and energy directly promoting the welfare of women and children. She was diagnosed with breast cancer that same year, and while she had decided to leave the show before she got sick, her illness reinforced her decision to reorder her priorities. After a lot of research, she joined the board of Save the Children, the worldwide relief organization, and Charlie MacCormack, then the organizations CEO, recalls meeting Cokie for the first time: She talked about her commitment to girls and women, it was pretty central to what she hoped would be her legacy. It was clear that was really consuming to her, a passion, and thats what we needed. I asked if she talked about her diagnosis, and MacCormack, whose wife also had breast cancer, replied, Oh yes. She said Ive got to rebalance my time, because I dont know how much time I have left.