For Stella, who let me watch TV

And for my mother, who didn't

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407028811

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Published in 2009 by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing

A Random House Group company

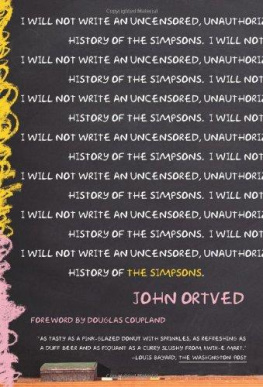

First published in the USA by Faber and Faber as The Simpsons

Copyright John Ortved

John Ortved has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781407028811

Version 1.0

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visit

www.rbooks.co.uk

Foreword

BY DOUGLAS COUPLAND

Here it is, two decades later. I never thought that as I aged I would develop Groundskeeper Willie Eyebrow Syndrome (GWES), and yet nature has cruelly slotted me with it. And here it is, two decades later, and I still can't go near cafeteria food without thinking of Bart Simpson's corrupt lunch lady and her massive cartons of beef hearts on the rear loading dock. And finally, here it is, two decades later, and despite my urbane demeanor and general support for worthy causes, I can't help but wonder how cozy Mr. Burns's pair of loafers made of former gophers would feel.

I remember back at the start of the kraziness, back when Fox was a plucky young network with a gleam in its eye, with the amusing-but-doomed Tracey Ullman Show operating at the tent pole of its aspiring avant-garde sitcom regime. I remember in that show seeing an amusing animation clip in which a very badly drawn and animated Matt Groening character barfed into a dish of mints in a doctor's waiting room. (I think that's what it was; my brain cells may well now have the neuro equivalent of GWES.) I remember thinking to myself, Man, I can't believe they showed barfing on TVthat was so transgressive. Thank you, Fox, for opening new doors through which satire may enter.

And so the Simpsons have been barfing into dishes of mints for more than two decades. Actually, to be technically correct, it's the Family Guy characters who do the avant-garde barfing these days. But the Simpsons did open that door, and in so doing have created a self-sustaining mythology of archetypes and stories that unite mankind far better than NATO, Esperanto, or metric. During book tours I used to hand out cards and ask people to write down the name of their favorite Simpsons character and then hand it in at the end of the reading. Surprisingly, it wasn't Bart or Homer or the big kahunas that were the favoritesit was the peripheral characters that were beloved: Duff Man with his Ooh yeah! and his tendency to refer to himself in the third person; Selma, the beloved chain-smoking lesbian hag; or (possibly the most obscure character of all) alcoholic marketing cipher Lindsay Nagle.

The larger goal of asking people to write down the names of their favorite character was simply to create a nice mood in the room, and it always worked. You can find people in just about any mood, and after a bit of Simpsons banter, a more cheerful psychic homeostasis emerges. I remember in a Quebec hardware store, a teenage girl at the end of an aisle holding up a blue feather duster and saying to her friend, "C'est Marge Simpson." Now that's world peace in action.

I suppose having GWES is simply a subset of a larger condition called growing old. I look in the mirror and am daily insulted by myself, and yet the Simpsons remain as young and fresh as alwaysexcept for the earlier episodes, which aren't as well drawn as in later episodes, the ones in which Homer sounds funny, and which are too weird to watch repeatedly. (Fans know what I mean.) I like the fact that we don't know where Springfield is. I like the fact that you still never really know where an episode is going to take youto Capitol City, to Epcot, to Winnipeg, or to a dash of mints filled with barf.

You may be entering this book with ambivalencemaybe it's not a good thing to see how the show comes into being; maybe it's best not to see the beef hearts being turned into lunch. But maybe you'll come away from the book fortified and more eager than ever to turn the TiVo to Fox on Sunday nights. Forget Disneyland. Sunday night at eight is the happiest place on earth. Ooh yeah!

Preface

If you bought this book to learn something about comedy or its workings, I suggest you return it and put the money toward a copy of Freaks and Geeks on DVD. Comedy can't really be explained with words, and Judd Apatow's brilliant and short-lived series sheds more light on the subject than I could ever hope to.

In a remarkable scene from the episode "Dead Dogs and Gym Teachers," Bill Haverchuk, a young teenager and perhaps the geekiest of geeks, comes home to an empty house after another humiliating day at school (he is fatherless; his mother, who works as a waitress, is dating the gym coach he loathes). Making himself a cheese sandwich, he sits down in front of the television. Immersed in Garry Shandling and the loneliness that will define his adolescent life, Bill begins to laugh as The Who's "I'm One" plays over the action. He laughs so hard the food falls from his mouth. His face scrunches into apoplectic expressions of joy. It's a deeply poignant moment, representing not only the alienation and indignities many of us suffered as high school losers, but our search for solace, and comedy's ability to save us.

The series is Apatow's finest work, and the touchstone in his path to becoming the James L. Brooks for my generationdeveloping thoughtful comedy blockbusters with fully realized and deeply flawed characters. Brent Forrester, who has worked with Apatow, told me that the scene was based on Judd's personal experience, which I can believe. But really, it could be any of us.

I'm stealing from George Meyer here, but I like to laugh more than the average person. I'm not sure where it fits on my list, but it's up there. I and those of us who love comedy feel as though it is essential because, as one of James L. Brook's associates put it, "Funny helps you live through the pain." I can remember countless weekend evenings, long past the time I should have been going to parties or on dates, spent alone or with a single friend, eating pizza and watching The Simpsons, Spaceballs, Saturday Night Live, or Waiting for Guffman. And I loved it, not because I didn't know there was another world that I was missing but because this really was the next best thing; if I couldn't laugh with others, I would laugh by myself.