Holy Lands:

Reviving Pluralism in the Middle East

Copyright 2016 by Nicolas Pelham

All rights reserved

Published by Columbia Global Reports

91 Claremont Avenue, Suite 515

New York, NY 10027

globalreports.columbia.edu

facebook.com/columbiaglobalreports

@columbiaGR

Library of Congress Control Number:

2015949787

ISBN: 978-09909763-5-6

Book design by Strick&Williams

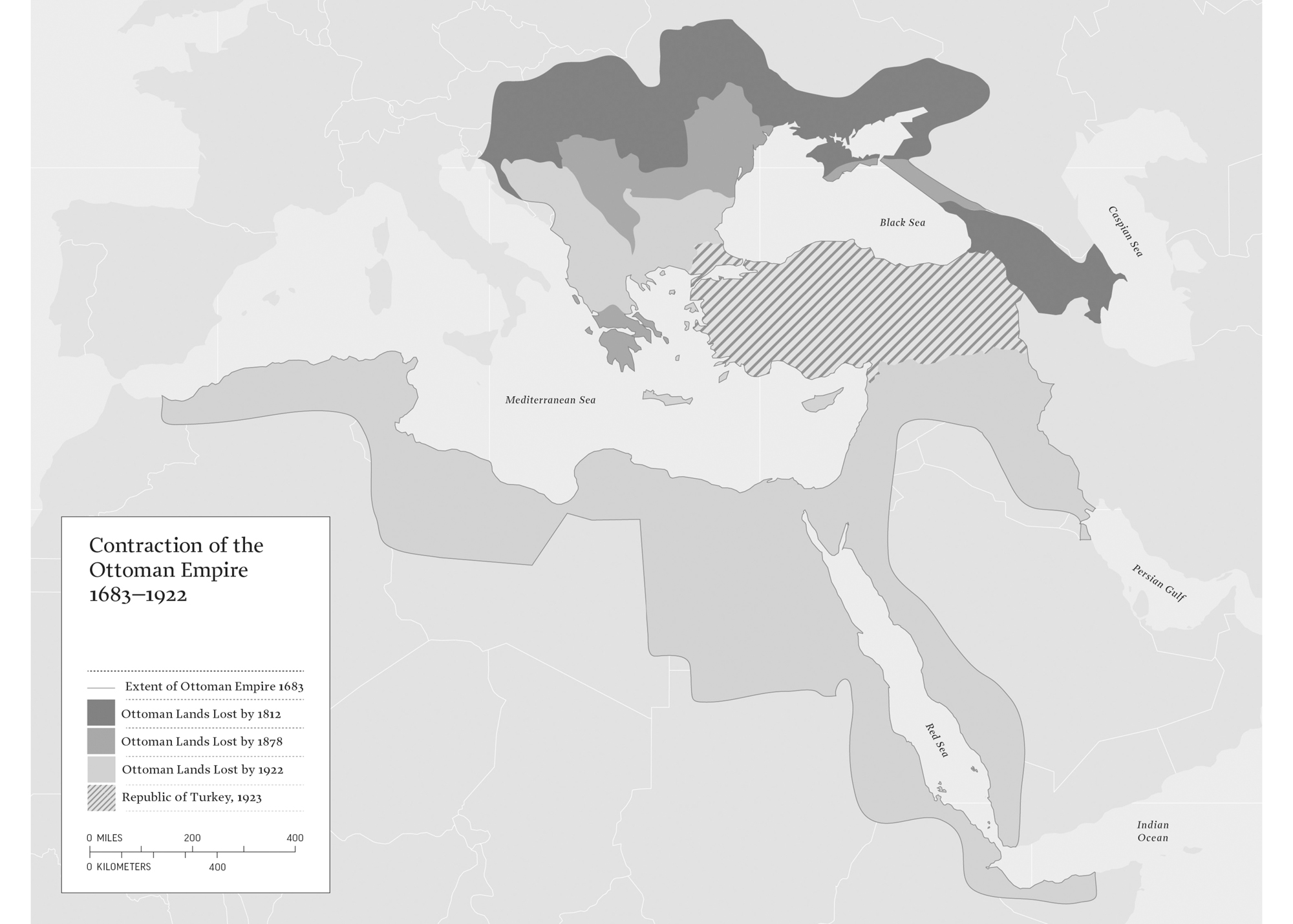

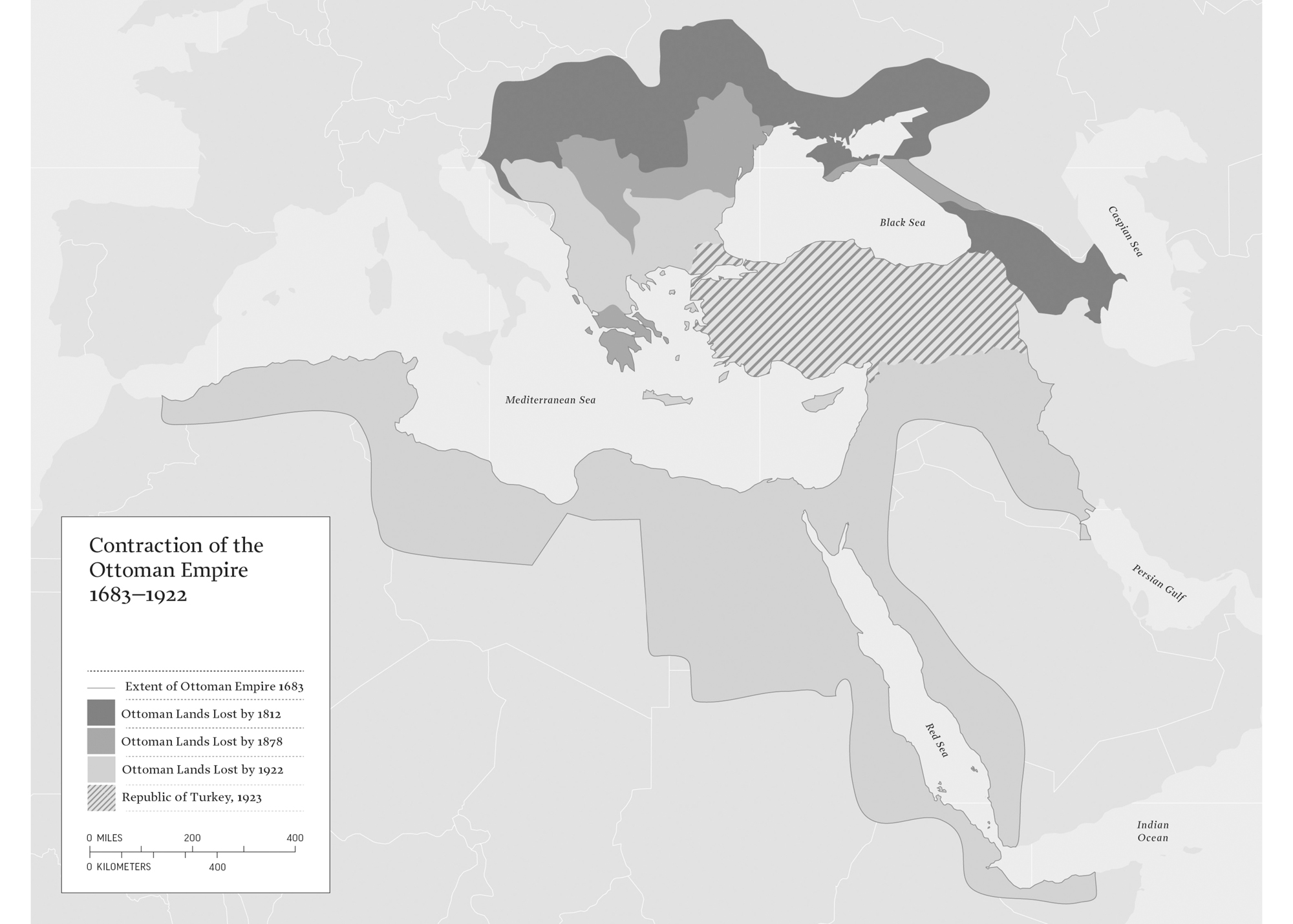

Map design by Jeffrey L. Ward

Author photograph by Lipika Pelham

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

Mustafa Kemal Atatrk

First president of Turkey, 192338

Recep Tayyip Erdoan

President of Turkey, 2014current

Ara Sarafian

British-Armenian historian of the Armenian genocide

David Ben-Gurion

First prime minister of Israel, 195563

Benjamin Netanyahu

Current prime minister of Israel

Ilan Shohat

Mayor of Safed

Yona Yahav

Mayor of Haifa

Shimon Gafsou

Mayor of Nazareth Illit

Haviva Aranyi

Holocaust survivor

Yehuda Bauer

Israeli historian of the Holocaust

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab

Arabian founder of Wahhabism/Salafism

Izz ad-Din al-Qassam

Syrian cleric and an architect of modern Sunni jihadism

Abdullah Azzam

Palestinian cleric and founding member of al-Qaeda

Osama bin Laden

Arabian founder of al-Qaeda

Abu Qatada al-Filistini

Jordanian leader of Palestinian jihadism

Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi

Jordanian-Palestinian spiritual mentor of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

Jordanian founder of al-Qaeda in Iraq/the Islamic State

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

Iraqi leader of the Islamic State

Muqtada al-Sadr

Iraqi leader of the Sadrist Movement

Saddam Hussein

President of Iraq, 19792003

Nouri al-Maliki

Prime minister of Iraq, 200614

Haider al-Abadi

Prime minister of Iraq, 2014current

Ali Sistani

Leading grand ayatollah in Najaf

Abu Jaafar al-Darraji

Senior commander of the Badr Organization

Mohammed Dahlan

Palestinian politician, security advisor to Abu Dhabi crown prince

Mansour Malik

Founder, Islamic Law Chambers

Sayyid Abu Musameh

Former leader of Hamas in Gaza

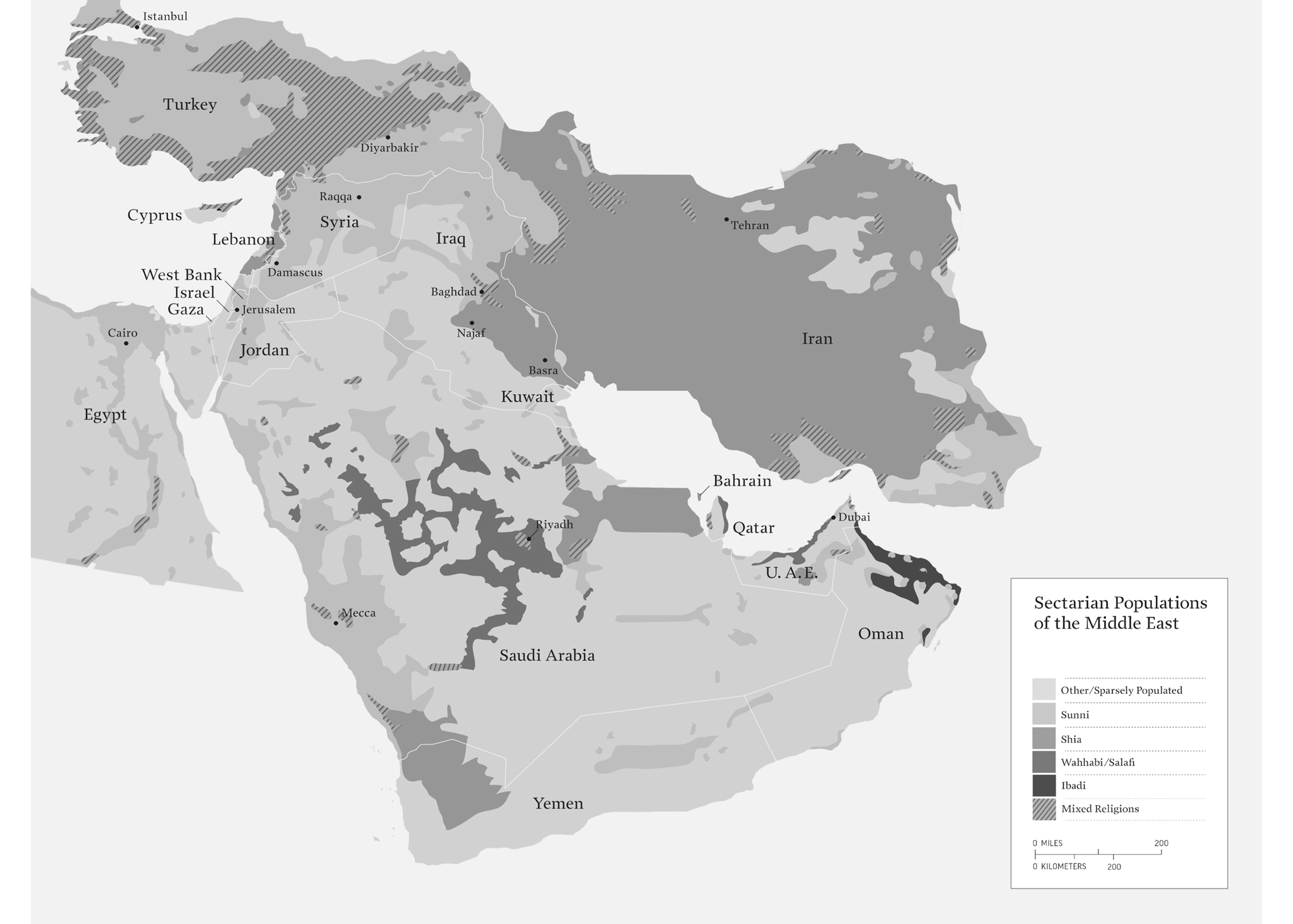

Like many before me, my career in the Middle East was born of the thrill of the regions diversity. In Damascus, where I studied Arabic in the 1990s, going to different places of worship was as natural as a stroll in the park. Mornings might take in a synagogue service, lunchtimes an Orthodox mass, evenings the salah prayer at Ibn Taymiyas mosque, followed by a late-night hammam, a Turkish bath. Faith was theatrical, spectacular, wholesome, and uplifting.

It feels a lost world. At work, my reporting is limited ever more to the dreary cycle of violence. Instead of covering the regions vibrancy and creativity, most of my articles describe its demise. More than 100,000 killed in one of Middle Easts bloodiest years, was the headline with which the Financial Times rang in the New Year in 2015. None of the conflicts it listedin Syria, Iraq, Israel and Palestine, Yemen, and Libyashowed any sign of waning, let alone ending. With each article, ones admiration for the region turns that bit more into pity.

This book is born of the gnawing question of how a region that for half a millennium was a global exemplar of pluralism and religious harmony has become the least tolerant and stable place on the planet. Through six essays from the field, the book explores the causes of the decline, and offers a few pointers for a recovery. Those hoping for a prescriptive template for resolving the Middle Easts multiple crises will be disappointed. What they will find is a fresh approach for examining what has gone wrong, and perhaps a paradigm for understanding what might put it right.

In 1923, a Norwegian arctic explorer, Nobel Peace Prize winner, and the first League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Fridtjof Nansen, devised a mass population exchange that became known as the Lausanne Convention. Unmixing the populations of the Near East will tend to secure true pacification of the Near East, he reasoned. Building on the Wilsonian principles of national self-determination, his convention wound up the last vestiges of the Ottoman Empire in southeastern Europe after six centuries of religious co-existence. It provided for the compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Moslem religion established in Greek territory. In the months that followed, 1.6 million people were displaced across the dying empire, many from communities that had never seen sectarian conflict.

Forcible population transfer was not a novel phenomenon. Encouraged by Europes Christian great powers, for almost a century Christian nationalist movements had sloughed off Ottoman rule in southeastern Europe and purged their countries of their Muslim past. Russia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, and Greece killed and expelled hundreds of thousands of Muslims, as if revisiting Spains Reconquista on southeastern Europe. But Nansen was the first to achieve diplomatically what others had achieved by war, and give the transformation of the Ottoman Empires heterogeneous society into homogeneous societies an international stamp of approval. George Curzon, who as Britains foreign secretary was one of the key negotiators, hailed the advantages which would ultimately accrue to both countries from a greater homogeneity of population, and set about unmixing and partitioning Britains other colonies along similar lines. The British government partitioned first Jerusalemin which under Ottoman rule Muslims, Christians, and Jews all mingled togetherinto separate religious quarters, and then Palestine itself.

Communal segregation had ancient roots. From the outset, Ottoman sultans had administered their diverse empire on sectarian lines, devolving authority to the leaders of their multiple faith communities, or millets. Patriarchs, chief rabbis, and Muslim clerics headed semi-autonomous theocracies that applied religious laws. But while the millets governed their respective co-religionists, they had no power over land. The empires many millets shared the same towns and villages with other millets. There were no ghettoes or confessional enclaves. Territorially, the powers of their respective leaders overlapped. I have called this system of overlapping religious powers milletocracy.

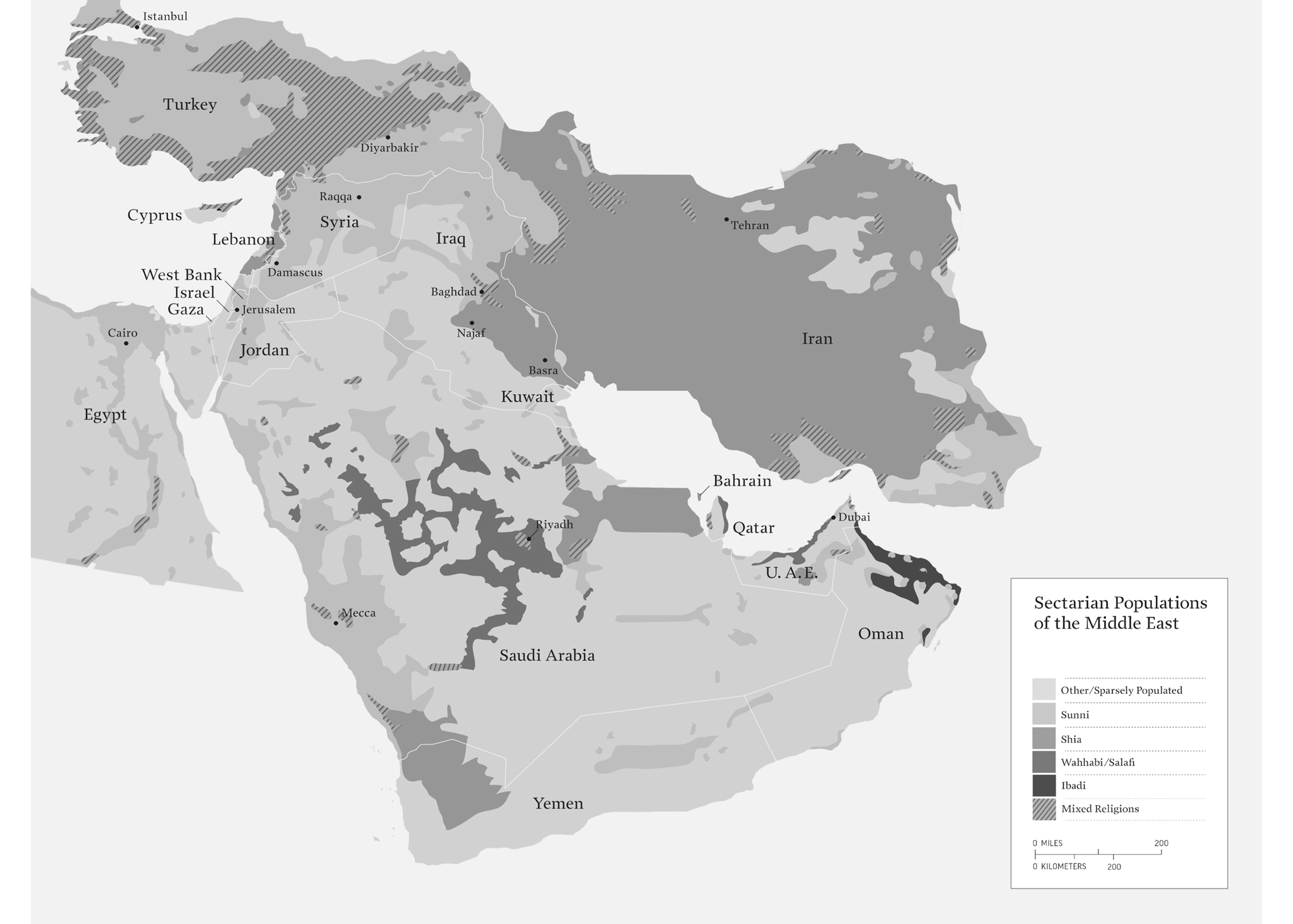

The unmixing of sects that the Lausanne Convention propagated in the Near East triggered a century of wars designed to turn holy communities into holy lands. Millet fought and evicted millet in the struggle to create gerrymandered enclaves that turned religious minorities into majorities. Across the region, a heterogeneous population was subject to attempts to sift, order, and refashion it as a patchwork of homogeneous ones. Far from delivering the pacification Nansen promised, the process has resulted in an ongoing program of secticide, or milleticide, which, as the