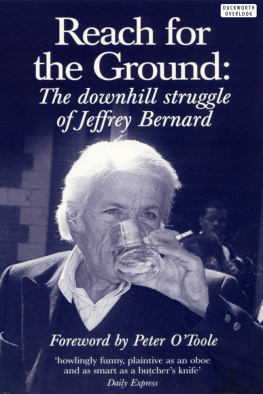

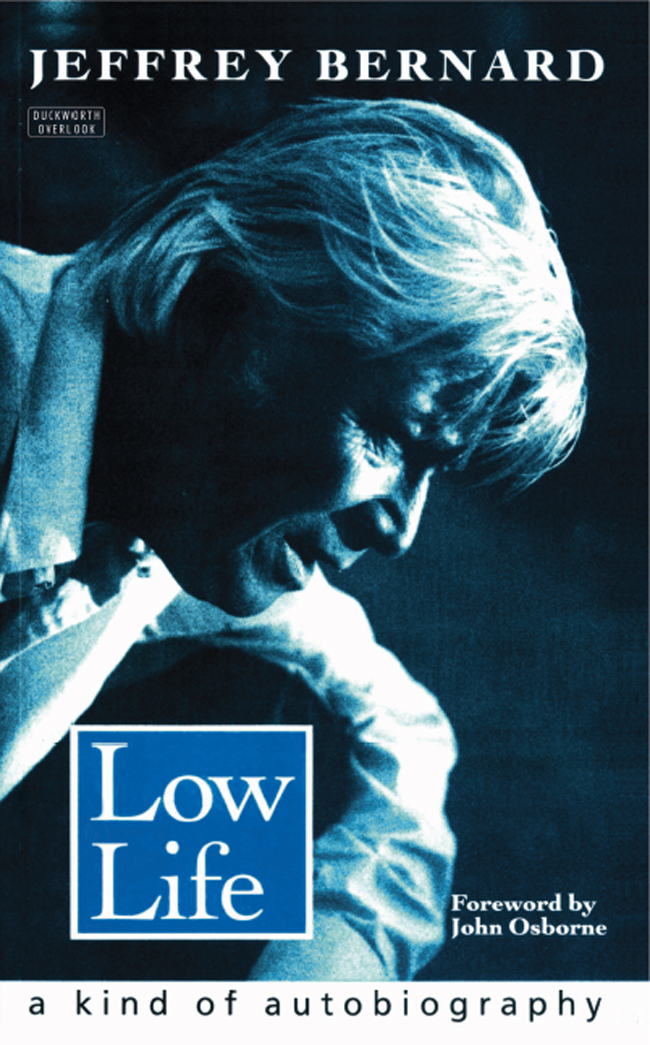

LOW LIFE

Low Life

a kind of autobiography

Jeffrey Bernard

Duckworth Overlook

For Isabel Bernard

with love

This eBook edition first published in 2014 by

Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales, please contact

or write to us at the address above

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

First published in 1986 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd

Main text 1986 by the Spectator

Elizabeth Smarts verses 1985 by Elizabeth Smart

Introduction 1986 by Jeffrey Bernard

Foreword 1986 by Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The main text of this book is selected from Jeffrey Bernards Low Life column in the Spectator.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBNs

Paperback: 978-0-7156-2445-6

Kindle: 978-0-7156-4942-8

ePub: 978-0-7156-4943-5

Library PDF: 978-0-7156-4944-2

Manufactured in Great Britain by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

Contents

Foreword

by John Osborne

I have come to terms with the fact that my dinner is in the oven and always will be.

Jeffrey Bernard is the Tony Hancock of journalism (the Last Supper menu will be brown Windsor soup and minced beef with cabbage and boiled potatoes), although his reports from the front of bullet-biting endured during his enforced periods of capture at the hands of a puritan and punitive medical profession are more harrowing than the fantasy loss of an armful of blood.

Unconstrained by lofty journalistic mannerisms, this collection of his columns in The Spectator, unlike most conceited cobbled books, has its own autobiographical momentum and unity. The sum, for once, is indeed greater than the weekly parts. There is live, squirming and bloody sinew beneath this continuing suicidal account of fragility. Failure with women, drink, doctors, horses (the usual) is transformed by his telling of it into a long, dark, heroic progress to the visible and disregarded underworld.

One turns first and naturally each Friday to Low Life; the opening sentences can cheer the heart of every devout depressive: Its been a perfectly dreadful week , The past few days have been just about as bad as can be , For a moment I thought I was going mad , I wasnt feeling very well last week , On Monday I met a black bird with thrush . Dateline: The Middlesex Hospital.

His impeccable contempt is his energy: Guardian readers, Americans, the French, Fleet Street hackettes, spivs like Andr Previn and Michael Parkinson, The Sun, West Indian nurses, wheat germ and Joan of Arc, Real Ale, Bernard Levin, Jill Tweedie, Sir Peter Hall, electric typewriters, free-range women and the cruelties of marriage. The aim, fired from the shattered hip and prone in the gutter, like a dying bandits, goes straight to the heart of the heartless.

He regains his feet from these pages, showing infinite gratitude to his possibly long-suffering friends, shaking himself all over them like a beloved Labrador. One of the things I loathed most about school, the army and regular employment was the feeling that I was missing something and that in the pubs, clubs, cafs, dives and racecourse bars there was some sort of magic in practice that I wasnt able to conjure with.

But he did, and the unintimidated magic has never left him. His fantasies, at their most poetic, owe far more to Swift than to Smirnoff: Id very much like to wake up one morning with a cow of the Friesian variety and walk her down to Soho to the Coach and Horses, stopping on the way to buy twenty Players, ply her with vodkas until closing time, whip her off to an Indian restaurant, take her up to the Colony Room till 5.30 and then to the Yorkminster, Swiss Tavern, Three Greyhounds, get beaten up by Chinese waiters at midnight, have a row with a taxi driver, set the bed on fire, put it out with tears and then wake up on the floor. Could you then milk the said cow? I doubt it.

Jeffrey Bernard has always been that fine figure and bane of prigs, schoolmasters and pushy careerists, a Bad Influence. What such people always overlook is that the renegades they abhor so are the least likely to want to exert influence, of all things, whether by persuasion or example. Bad influences might be envied their irresponsible freedoms but not their forfeiture of approved opinion; the country is presently stuffed with every invented machinery imaginable, committees, boards and councils, all devoted to the folly of good influences.

I most enjoyed the company of boys who were in trouble. They were the irreverent ones who couldnt be fooled into accepting the solemn hokum of school life or the swotting, athletic toadies who would become the fearful workaholics, young executives and flash entrepreneurs of today.

Bernard is not merely a journalist, but a grim, brave and funny diarist of the times in which he is a snarling participant. And like all the most engaged historians, he has written his own epitaph to match the mood of those times: It stinks but its the stink I know.

He possesses courage and style in abundance and his eye for physical detail, both in delight and in distress, is as astonishing and stimulating as anything in Pepys or Boswell. The felicity of style has everything to do with courage. Alcohol has never seriously blighted an energetic or creative nature. It is workaholism that degrades and abuses commonsense. Workaholics Anonymous I would drink to that any old day. Bernard sniffs out priggism, phoneys and officious banality like almost no one else: banal ambition which saps all proportion, seemliness, moral sense, and fires the mediocres, plodding and unscrupulous to everlasting vasty hells of covetousness and aggrandisement. I realised in those dives in Soho that there is no virtue in work for its own sake. Such things should be known by any fool but seem only to reveal themselves to the weary but unvanquished wise.

To get to the business of drink: alcoholic is the pejorative which the thrusting achievers and the gravely concerned would apply to the likes of Bernard. He is a Heavy Drinker, in the company of Falstaff or Dr Johnson. Heavy Drinkers are not to be confused with alcoholics or modern drug-addicts. Heavy Drinkers may be often tiresome, boring and selfish, but love of good company and friendship is usually one of their saving gifts. If they make harsh demands, they give of themselves unreservedly. Sometimes the gift may be restricted to simply living their art rather than transmitting it into art or literature, but as often as not they do both. English literature would be pretty thinned down if it practitioners had paid heed to Government pamphlets on the dangers of drink. Coleridge may be a tricky advertisement for laudanum, but Smirnoff should boost its products as the blessed muse of Jeffrey Bernard.

How could one not love and admire a man who says: It was very soothing in much the same way as a cold lavatory pan is when pressed against the forehead when one is being sick. This happens frequently when opening buff envelopes. The recognition is instantaneous. Or this about holidays: I cant wait for them and yet I am always pleased to get back to this rathole which I feel so safe in despite being surrounded by danger. The messages pushed out from under the rathole door put us in debt to him, and all the duns, doctors and Inland Revenue Men should cross themselves and file abjectly away.