Table of Contents

Guide

I will be forever grateful to my husband, Greg Salvatori, who patiently supported and encouraged me through the years of research and writing. I cant imagine this book being completed without him. And I cant imagine a good photograph of myself without his beautiful eyes behind the camera. It is Greg, to whom I dedicate this book, who always finds a way to put me in the best light. And I hope I do the same for him.

My extraordinary agent, Deirdre Mullane, believed in this project almost from the moment the proposal arrived in her inbox. Her enthusiasm and comments, as well as her countless hours with the proposal and manuscript, were crucial to shaping what this book has become.

It has been a great pleasure to work with the smart and talented people at Counterpoint. Executive editor Dan Smetanka understood and cared about this book from our first phone conversation. He is the ideal editor who can balance between encouragement, questioning, and good humor. The often unsung hero of any book is the copy editor, and Trent Duffy was no exception. He made the book more precise in prose and meaning, and for that I am forever grateful. Im also grateful for Donna Chengs lovely cover design and Jordan Koluchs book design, and how Jordan kept the editing process amazingly on track. Katie Boland answered so many of my questions with patience, and educated me on the ins and outs of book events. My publicist, Becky Kraemer, shaped the public life of the book with expertise and loving care.

The origins of this project were planted several years ago in my dissertation at New York University. Philip Brian Harper, Lisa Duggan, Andrew Ross, and Carolyn Dinshaw helped me frame the central research questions and ideas of the dissertation. Support for the dissertation came from a James D. Woods III Fellowship from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the City University of New York, and a Deans Dissertation Fellowship from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at New York University.

Without the dedicated work of so many anonymous librarians and archivists across the country who labored to preserve thousands of old newspapers and then create a digital database of them, this book would not have been possible. Staff at the Bobst Library at New York University and the New York Public Library provided valuable assistance at various stages of my research. Timothy Young at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University offered crucial insights about the Van Vechten scrapbooks.

I am grateful to my many students at New York University and Princeton who have helped me think about the nature of creative nonfiction storytelling, and the meanings of crime stories as historical documents.

There have been so many friends and colleagues who have generously listened to me talk, obsess, and stress about the research and writing over the years: Scott Gerace, Patrick McCreery, Janet Burstein, Kate Caulkin, Carley Moore, Matt Longabucco, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Chad Heap, Frances Guerin, Matthew Roy, Henry Castrillon, Jen Meyer, Emily Sweeney, Patrick Gudon, Mary Lou Longworth, Ifeona Fulani, Chris Packard, Peter Nickowitz, Lidia Salvatori, Allen Ellenzweig, John Howard, Amanda Herold-Marme, Cree Lefavour, Bridget Brown, Erin McMurray, Sean McNeal, Mary Helen Kolisnyk, Melissa Haley, Donette Francis, Cyndi Mitchell, Bob Mills, Martin Dines, Suzanne Menghraj, Nina DAlessandro, and P. G. Kain.

And finally, my parents, Jack and Gloria, who sacrificed much to provide me with opportunities they never had, supported the choices I have made over the years, and shaped the person I have become.

Greg Salvatori

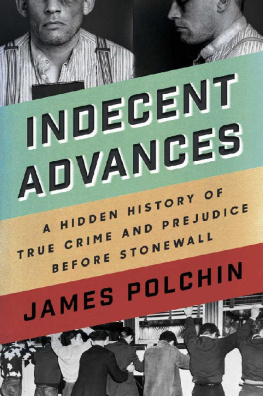

JAMES POLCHIN, PhD, has taught at the Princeton Writing Program, the Parsons School of Design, the New School for Public Engagement, and the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. A clinical professor at New York University, he lives in New York City with his husband, the photographer Greg Salvatori. Indecent Advances is his first book. You can follow him at @jamespolchin.

MURDERED IN HOTEL ROOM

On November 4, 1920, the front page of the New York Daily News announced in large block letters a disturbing milestone in the city: the one hundredth murder of the year. The accompanying article detailed the fatal beating of Leeds Vaughn Waters in a room at the Plymouth Hotel on West Thirty-Eighth Street. The tabloid reported that police had found Waters slumped on the floor with a fractured jaw and skull and a deep wound over his left eye, which was apparently inflicted by a blunt instrument. Waters was the scion of a wealthy New England family who had made its fortune in piano manufacturing. Since his graduation from Columbia College in 1896, he had lived much of his life in London, England. The Daily News described the forty-eight-year-old victims life as a series of kaleidoscopic glimpses of social activities in North and South America, in England, and on the continent.

As there was no apparent robbery, New York City detectives were baffled by the motive for the crime. The editors, however, speculated about the murder by casting doubts on the character of the victim himself. According to friends, the newspaper reported, Waters has never been engaged in industry and has never been known to exert himself to labor, adding riches and idleness are shown as powerful influences toward his tragic end. The term idleness was often used in the press in the 1920s to hint at moral and criminal duplicities. How he was lured from his usual haunts along the rosy path of luxury, the newspaper asked, to hostelry of the character of that in which he was slain is a point of mystery which no one has been able to solve.

In the coming days, newspapers in New York and across the country would pursue this question, with articles that detailed the last hours of Waterss life. Readers learned he spent the evening at the Delta Kappa Epsilon Club, a thirteen-story, private gentlemens club on East Forty-Fourth Street, where he had been a member since his college days. News accounts referring to Waters as a clubman signaled his social standing. Inside the brick and stone building, DKE men enjoyed a gymnasium with squash courts, a mahogany-paneled taproom, a rooftop caf, and five floors of guest rooms. Waters spent most of the evening playing cards, indulging his love of gambling. Around one in the morning he told his friends he was leaving to return to Bronxville, a suburb north of the city where he was staying with his mother at her hotel.

Instead of going north, however, Waters instructed the taxi driver to take him a few blocks west to Times Square, where, as The New York Times conjectured, he met a swarthy, dark-skinned man, who was believed to be the one who shared the hotel room. In 1920, Times Square still had the reputation of a genteel theater district, though queer encounters were common in the area. Its seedier nightlife would emerge in the 1930s during the Great Depression. A few blocks west of Times Square was the more notorious Tenderloin neighborhood, known for its overcrowded tenements, crime, and vice. The Tenderloin was also known for its queer men, particularly in the West Forties and Fifties, many of whom worked in the theaters. It was in the Tenderloin, at Ninth Avenue and Forty-Fourth Street, that Waters and his companion allegedly dined at a restaurant in the early morning hours. Witnesses reported that Waters bought a meal for his companion and an apple for himself.

Eventually they arrived at the Plymouth Hotel at six in the morning as the yellow light of dawn filled the sky. John Carney, the night clerk at the Plymouth Hotel, would tell police that the two men made a strange sight as they entered the lobby. While Waters was expensively dressed, his companion wore shabby clothes and seemed to be of a much inferior social standing. In a front-page article headlined Murdered in Hotel Room, the

Next page