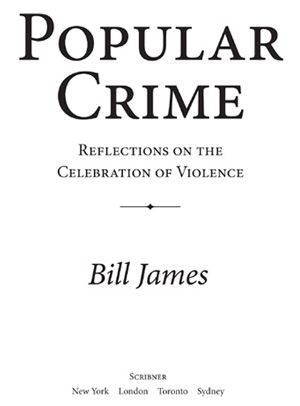

ALSO BY BILL JAMES

The Bill James Baseball Abstract

The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract

This Time Lets Not Eat the Bones

The Bill James Baseball Book

The Politics of Glory

The Bill James Player Ratings Book

The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers

The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract

Win Shares

The Bill James Handbook

The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (with Rob Neyer)

The Bill James Gold Mine

Scribner

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2011 by Bill James

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner

Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition May 2011

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under

license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers

Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Designed by Carla Jayne Jones

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010036180

ISBN 978-1-4165-5273-4

ISBN 978-1-4391-8272-7 (ebook)

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO PHYLLIS MCCARTHY

MY WIFES MOST GRACIOUS MOTHER

Contents

POPULAR CRIME

I

I n Rome in the year 24 AD, the praetor Plautius Silvanus pushed his wife Apronia out of the window in the middle of the night. They hadnt been married very long, or, we might guess, very happily. It was a high window, and she did not survive the fall.

Silvanus was a member of one of Romes most celebrated and successful families. His father, also Plautius Silvanus, had been consul in 2 BCE. His grandmother, Urgulania, was a close friend of the empress, and a cousin, Urgulanilla, was then married to the man who would later become the emperor Claudius.

Apronias father rushed to the palace and awakened the emperor Tiberius. Tiberius went immediately to the scene of the crime, where he saw obvious signs of a struggle and the marks of Apronia being forced out the window. Silvanus had no explanation. He claimed that he had been asleep at the time, and that Apronia must have leapt to her death. He was arrested, judges were appointed, and Tiberius presented his evidence to the Roman senate.

A great public scandal arose, in the midst of which Urgulania sent her grandson a dagger. This was taken to be a hint. Silvanus attempted to stab himself with the dagger, and, that failing, apparently enlisted the aid of confederates; in any case, Tacitus records that he allowed his veins to be opened, and was soon gone.

There was still to be a trial, however. Silvanus first wife, Numantina, was put on trial on charges of having driven her late ex-husband insane with incantations and potions what we would now call witchcraft. She was acquitted.

Silvanus family was destroyed by the scandal. Claudius divorced Urgulanilla, who was believed to have been implicated in the matter in some opaque way. The grandmother disappears from history.

In 61 AD the Prefect of the city of Rome, L. Pedanius Secundus, became embroiled in a dispute with one of his slaves, either because he had agreed to release the slave for a price and then reneged on the dealthe story told by the slaveor because Pedanius and the slave had both fallen in love with the same slave boy who was kept as a prostitute, which was apparently the story circulated in the streets. In any case, Pedanius was murdered by the slave.

Roman law required that, when a slave murdered his master, all of the slaves residing in the household were to be executedin fact, even if the master died accidentally within his house, the slaves were sometimes executed for failing to protect the master. Pedanius had 400 slaves. The law had been as it was for hundreds of years, Roman law being harder to change than the course of a river, and there had been cases before in which large numbers of slaves had been executed, but now people were losing respect for the old values, and the slaves no longer saw the point in this tradition. Crowds of plebsrank-and-file civilians, neither slaves nor aristocracygathered to protest the executions. Rioting broke out, and not for the first time, incidentally. Rioting had erupted over the same issue at other times through the centuries.

The senate debated the matter, and most of the senators realized that the executions were unjust. They were unable to block implementation of the law, however, and the order was given that the executions must be carried out. Troops attempted to seize the slaves, but a crowd gathered to defend them, armed with stones and torches, and the soldiers were beaten back. By now Claudius stepson Nero was the emperor, never known for his civility. Nero ordered thousands of soldiers to the scene. The slaves were taken into custody, and legions of soldiers lined the streets along which they were taken to be put to death.

Ordinarily, crime stories sink gradually beneath the waves of history, as proper stiff-upper-lip historians are generally above re-telling them, but street riots are one of the things that sometimes cause them to float. On January 1, 1753, an 18-year-old girl disappeared from a country lane in an area which is now part of London, but which at that time linked London to the village of Whitechapel. Employed as a maid in London, Elizabeth Canning had spent New Years Day with her aunt and uncle in Whitechapel. As the holiday drew toward evening she headed back to London, and the aunt and uncle walked with her part of the way. With less than a mile to go along the thinly populated lane her relatives turned back, assuming that she would be safe making the last leg of the trek alone in the gathering dusk. In 1753, of course, the streets were unlit, and also, London had no regular police service. She had with her a little bit of money, what was left of her Christmas money, which was called a Christmas Box, and a mince pie that she was carrying as a treat for one of her younger brothers.

She failed to arrive back in London. What happened then is oddly familiar to us. Her mother immediately raised the alarm, and her friends, relatives and her employers immediately organized a volunteer search. Within hours of her disappearance they were knocking on doors throughout the area, and within two days they had covered much of London with advertisements and fliers asking for information and offering a small reward. Her disappearance attracted the attention of the city. Someone along the lane thought that he remembered hearing a woman scream about the time she disappeared.

The search, however, went nowhere for several weeks. On January 29, late in the evening, Miss Canning suddenly reappeared at her mothers house, looking so bedraggled that her mother, when first Elizabeth came through the door, had not the slightest idea who she was. She had bruises on her face and body, a bad cut near one ear, she was dirty and emaciated and the nice dress she had been wearing at the time she disappeared had been replaced by rags. Her mother screamed, and, in the crowded part of London where they lived, the house filled quickly with friends and curious neighbors.

Next page