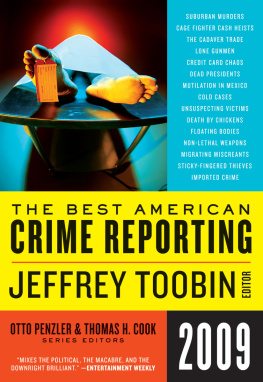

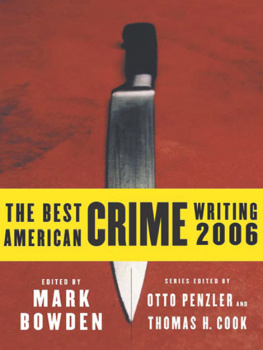

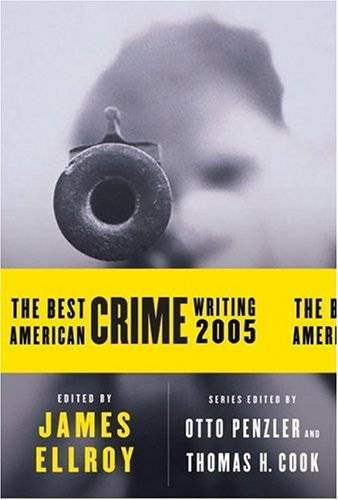

James Ellroy, Peter Landesman, Robert Draper, Skip Hollandsworth, David Grann, Clive Thompson, Jonathan Miles, Lawrence Wright, Craig Horowitz, Justin Kane, Jason Felch, Bruce Porter, Jeff Tietz, Stephen J. Dubner, Philip Weiss, Debra Miller Landau, Neil Swidey, James Ellroy

The Best American Crime Writing 2005

2005

The year 2004 wa s profoundly political. Thus it was not surprising that a great deal of newspaper and magazine space was given over to the Democratic primaries and, later, to the presidential campaign. Nonetheless, the best of our nation's crime writers were not silenced by the crashing symbols of our quadrennial bash. Amid all the hoopla, they made their voices heard, and the finest of those voices have been gathered into this, the fourth volume of Best American Crime Writing.

As in previous editions, the tone of those voices vary tremendously.

There is sadness in the voice of Peter Landesman as he relates the tragic plight of "The Girls Next Door." In "Stalking Her Killer," Philip Weiss's voice seems eternally haunted by a murder that was solvedbut never punished. Comic irony pervades Jonathan Miles's tale of bar-brawling, while the irony of Neil Swidey's "The Self-Destruction of an M.D." is very dark indeed. Bruce Porter, Justin Kane, and Jason Felch record a similarly dark descent in "A Long Way Down" and "To Catch an Oligarch." A similar descent leads to murder in Debra Miller Landau's riveting "Social Disgraces."

There is, as always, variety in subject matter as well, from the gentlemanly art of stealing silver in Stephen J. Dubner's "The Silver Thief," to simple larceny in Skip Hollandsworth's "The Family Man," to the maddening antics of Internet hackers described in Clive Thompson's "The Virus Underground," and finally to the terrible slaughter both threatened and envisioned by Lawrence Wright's "The Terror Web."

Apprehension, or the lack of it, is the subject of three of our distinguished contributors. Robert Draper chronicles the inexcusable escape of a group of deadly terrorists in "The ones that Got Away," while Craig Horowitz's "Anatomy of a Foiled Plot" details the fortunate capture of a group of criminals before they had a chance to commit their awesome crime.

Finally, there are certain pieces that simply defy categorization. Jeff Teitz's "Fine Disturbances" portrays in finely nuanced detail the intuitive brilliance of a great tracker. in "Mysterious Circumstances," David Grann investigates the death (by murder or misadventure) of the world's foremost collector of Sherlock Holmes memorabilia.

Here then, and with great pride, we present this year's collection of the Best American Crime Writing, tales that will delight and sadden you, inspire both awe and disbelief, but always stories that display, in full color, the variety of human malfeasance, and thus the poles not only of criminal experience, but the whole checkered history of our kind.

In terms of the nature and scope of this collection, we defined American crime writing as any factual story involving crime or the threat of a crime by an American or Canadian and published in the United States or Canada during the calendar year 2004. We examined a huge array of publications, though inevitably the preeminent ones attracted many of the best pieces. All national and large regional magzines were scanned, as well as nearly two hundred so-called little magazines, reviews and journals.

We welcome submissions by any writer, publisher, editor, agent or other interested party for Best American Crime Writing 2006. Please send a tear sheet with the name of the publication in which the article appeared, the date of publication and, if possible, the address of the author or representative. If first publication was in electronic format, a hard copy must be submitted. only articles actually published with a 2005 publication date are eligible. All submissions must be made by December 31, 2005; anything received after that date will not be read. This is not capricious. The nature of this book forces very tight deadlines which cannot be met if we are still reading in the middle of January.

Please send submissions to otto Penzler, The Mysterious Bookshop, 129 West 56th Street, New York, NY 10019. Submitted material cannot be returned. If you wish verification that material was received, please send a self-addressed stamped postcard. Thank you.

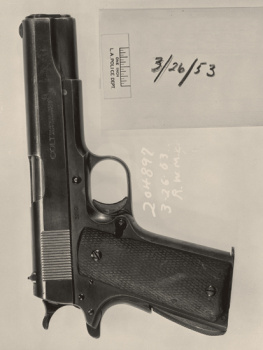

The chalk outline. Blood patterns. The sleep-fucked men standing by. The punk flanked by two squadroom bruisers. He's blinking back flashbulb glare. He's got one finger twirling. He's flipping the square world off.

Don DeLillo called it "the neon epic of Saturday night." It's Crime. It's the bottomless tale of the big wrong turn and the shortcut to Hell via cheap lust and cheaper kicks. It's meretricious appetite. It's moral forfeiture. It's society indicated for its complicity and dubious social theory. It's heroism. It's depravity. It's justice enacted both vindictively and indifferently. It's our voyeurism refracted.

We want to know. We need to know. We have to know. We don't want to live crime. We want our kicks once removed-on the screen or the page. It's our observer's license and innoculation against the crime virus itself. We want celebrity lowlifes and down-scale lives in duress. We want crime scenes explicated through scientific design. We want the riddle of a body dumped on a roadway hitched to payback in the electric chair.

We want it. We get it. Filmmakers, novelists, and journalists keep us supplied. They know how much we want our bloodthirsty thrills and how we want them circumscribed. Movies, TV, novels, and stories. Dramatic arcs. Beginnings, middles, and ends. Most crime is fed to us fictionally. The purveyors exploit genre strictures and serve up the kicks with hyperbole. We get car chases, multiple shootouts, and limitless sex. We get the psychopathic lifestyle. We get breathless excitement-because breathless excitement has always eclipsed psychological depth and social critique as the main engine of crime fiction in all its forms.

Herein lies the bullshit factor. Here we indict the most brilliant suppliers of the crime-fiction art. I'll proffer indictment Count number one-and cringe in the throes of self-indictment.

In the worldwide history of police work there has never been a single investigation that involved numerous gun battles, countless sexual escapades, pandemic political shake-ups, and revelations that define corrupt institutions and overall societies.

Count number one informs all subsidiary counts. That sweeping statement tells us that we are dealing with a garish narrative art. It's underpinnings are realistic. Its story potential is manifest-and as such, usurped by artists good, great, fair, poor, proficient, and incompetent. Crime fiction in all forms is crime fiction of the imagination. That fact enhances good and great crime fiction and dismisses the remainder. Crime fiction fails the reader/viewer/voyeur in only one way: It is not wholly true. And that severely fucks with our need to know.

True-crime TV shows, feature documentaries, full-length books and reportage. Revised narrative strictures.

You must report the truth. You can interpret it and in that sense shape it-but your factual duty is nonnegotiable.

As crime reader/viewer/voyeurs, we now cleave to this: our need to know has metamorphosed. We want less breathless excitement and more gravity. We still hold that observer's license and in-noculation card-but we're willing to get altogether closer now.

And, with that, a reward awaits. True-crime writing offers a less kineticized and more sobering set of thrills-chiefly couched in human revelation. A simple bottom line holds us: This Really Happened. The violated child, the crackhead dad, the cinderblock torture den. We're rewarded for getting close. We're buttressed in our safety. This isn't me, It's not my kid, I'm not going there.

Next page