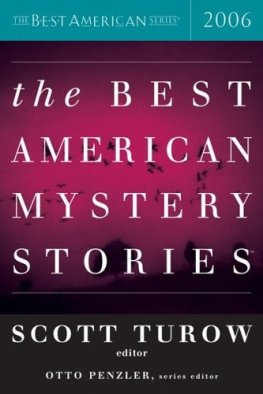

Bowden Mark, John Heilemann, Jimmy Breslin, Mark Jacobson, Skip Hollandsworth, Jeffrey Toobin, Robert Nelson, S. C. Gwynne, Paige Williams, Mary Battiata, Howard Blum, John Connolly, Richard Rubin, Chuck Hustmyre, Devin Friedman, Denise Grollmus, Deanne Stillman

The Best American Crime Writing 2006

In the late Darcy O'Brien's brilliant study of the Hillside Stranglers, Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi revel in the grim fantasy of a girl reared from birth exclusively for their pleasure. They watch and wait until the moment of flowering is reached, then rape and murder her. She is not a human being, but a plant grown for one dark harvest, then cut down.

Nothing in the history of crime writing more deeply illustrated the banal and commonplace source of criminal acts, that they are rooted in simple selfishness.

This year's edition of The Best American Crime Writing amply demonstrates the irreducible and uncomplicated truth so powerfully rendered by Darcy O'Brien. From the comic to the macabre, bumbling criminals to cunning ones, it is selfishness that rules the day. The continuum runs from narcissism to solipsism, the antisocial to the sociopathic, the Me who must go first to the Me besides whom there is no other.

This is not to say that things never get complicated, for as with Medusa's head, odd and coiling things may spring from a single source.

One of them is money. It is Saddam Hussein's money that provides the irresistible temptation in Devin Friedman's story of G.I. Joe corruption, while in Skip Hollandsworth's tale, it is the mere proximity of banks, along with an unlikely disguise, that beckons Cowboy Bob to "her" last ride. Howard Blum and John Connolly's "Hit Men in Blue?" suggests how wickedly money can be gained. Paige Williams's "How to Lose $100,000,000" demonstrates just how quickly it can be lost. Money is also the issue in Mary Battiata's riveting study of how little of it, when in dispute, can generate a murder.

Sex is predictably the issue at hand in other tales. How much it sometimes costs is the cautionary lesson learned in Mark Jacobson's "$2,000-an-Hour Woman." But, again, it is selfishness that provides the dark core of sexual crime. Escaping the consequences of that selfishness is the central focus of Denise Grollmus's "Sex Thief," and Robert Nelson's "Altar Ego." The failure to escape it forms the narrative thrust of John Heilemann's "The Choirboy," a heartrending tale ofjustice delayedbut not forever.

Escape also provides the thematic center of Richard Rubin's "Ghosts of Emmett Till," an escape that is offered, in this case, by society itself, time and conscience the only arbiters of how effective it will be. In S. C. Gwynne's "Dr. Evil," it is an honored profession's ineffective self-regulation that opens the escape hatch to a criminally incompetent doctor, horrendously botched surgery evidently still no reason to snatch the scalpel from his hand. In Chuck Hustmyre's "Blue on Blue," it is, at least briefly, the blind flash of a badge that provides a hiding place for a murderous cop, while in Deanne Stillman's riveting "The Great Mojave Manhunt," it is the desert waste that offers up concealment-nature, as always, indifferent to the kind of man it hides.

And, of course, there are always those who don't escape at all, as Jimmy Breslin illustrates to such comic effect in "The End of the Mob."

These then are the stories in this year's edition of The Best American Crime Writing, tales by turns harrowing and hilarious, a feast of human malfeasance chosen to satisfy the connoisseur's taste for what Browning called the "fine Felicity of wickedness" that is the just reward of reading fine true crime.

In terms of the nature and scope of this collection, we defined the subject matter as any factual story involving crime or the threat of a crime written by an American or Canadian that was first published in the calendar year 2005. Although we examined a huge array of publications, inevitably the preeminent ones attracted many of the best pieces. All national and large regional magazines were searched for appropriate material, as well as nearly two hundred so-called little magazines, reviews, and journals.

We welcome submissions by any writer, editor, publisher, agent, or other interested party for The Best American Crime Writing 2007. Please send the publication or a tear sheet with the name of the publication, the date on which the article appeared, and, if possible, the name and contact information for the author or representative. If the first publication was in electronic format, a hard copy must be submitted. Only material with a 2006 publication date is eligible. All submissions must be received no later than December 31, 2006; anything received after that date will not be read.This is neither arrogant nor capricious. The timely nature of the book forces very tight deadlines that cannot be met if we receive material later than that.The sooner we receive articles, the more favorable will be the light in which they are perused.

Please send submissions to Otto Penzler, The Mysterious Bookshop, 58 Warren Street, New York, NY 10007. Regretfully, no submissions can be returned. If you wish verification that material was received, please enclose a self-addressed stamped postcard.

Thank you, Otto Penzler and Thomas H. Cook New York, March 2006

The most typical way for a crime story to begin is with a date. S. C. Gwynne starts,"On June 8, 2003" Paige Williams's begins, "On Christmas Day 2002 "Sometimes the date comes with an hour and a minute: "Saturday, March 4, 1995. 1:55 a.m.," opens Chuck Hustmyre's.

Precision, because when you are describing someone committing a crime, you want to make sure you've got your facts straight; because most crime stories are based at least in part on trials and police files, and reflect the preoccupation of the criminal justice system with proof:This specific transgression of the law was committed in exactly this way at precisely this time against the herein named victim, and warrants precisely this verdict and punishment; but ultimately because the crime story is about something more than assigning blame and retribution. What fascinates us is the moment when things slippedoffthe rails. It's the same thing that prompts filmmakers to slow down the camera at the moment of impact, or breakdown. It's the point where there was a tear in the social fabric, a clear crossing of the line that defines ordinary life, decency, civil discourse, honest commerce, or acceptable behavior.When exactly-"Now, on the last Monday of November 2004," writes John Heilemann-grounds the transgression in reality, which is itself thrilling, because what scares us about crime is not its strangeness, but its familiarity. The consequences, the things that concern the judges, juries, and police, are about putting things right, restoring the fractured social order or contract, but we know that in a deeper sense things can rarely be put right, and that the real world, as opposed to the imaginary order of laws and contracts, is much much messier and more interesting. So we settle in to read on. Because the story isn't about blame and punishment, it's about who, what, when, where, how, and, most importantly, why.

In that greatest of true crime stories, In Cold Blood, enjoying a revival this year, Truman Capote built suspense toward the terrible murder of the Clutter family by walking us through the final day of each doomed family member, interrupting the ambling narrative with the steady drumbeat of their murderers' approach. When Perry Smith and Dick Hickock pull into the driveway of the Clutter home in darkness, Capote abruptly skips over the critical hours of the crime to the following morning, when neighbors discover the Clutters' bloody remains. He does this to maintain suspense-we all want to know exactly what happened inside that house-and keep us reading but also because he doesn't want to describe the crime until he has laid the groundwork for us to understand why it was committed. In Cold Blood isn't a whodunit, it's a why-dunit.

Next page