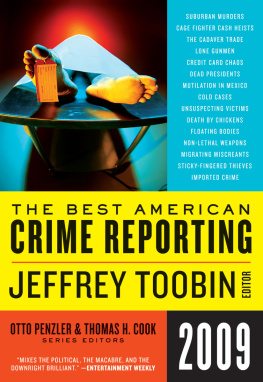

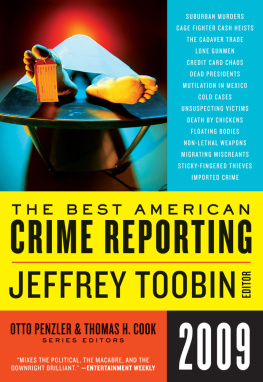

I F CRIME DIDNT PAY, as none other than G. Gordon Liddy once noted, there wouldnt be any. The varied ways in which crime can payat least in the short runare amply represented in this years edition of The Best American Crime Reporting.

Take dead bodies, for example. As Dan P. Lee demonstrates in Body Snatchers, there is real money to be made in the cadaver trade. The overhead is light, just a few sharp saws and a little storage space (not necessarily refrigerated). And in terms of marketing, one only needs a few choice customers who dont ask too many questions.

Using other peoples credit cards can also be quite lucrative, according to Sabrina Rubin Erdelys The Fabulous Fraudulent Life of Jocelyn and Ed, though controlling debt is really a must when spending other peoples money.

Shoplifting may undoubtedly bring in a tidy income, but as John Colapinto warns in Stop, Thief! the sticky-fingered must be careful of many unseen eyes.

In some cases, however, boldness wins the prize, as it does in Breaking the Bank, L. Jon Wertheims story of cage fighter Lightning Lee Murray, mastermind of the largest cash heist in criminal history.

The preceding stories show crime at its most comic and unusual. Others in this years edition of The Best American Crime Reporting show it at its most tragic.

In Mark Araxs The Zankou Chicken Murders, a hugely successful family business drowns in a pool of blood. Blind prejudice claims a wholly innocent victim in R. Scott Moxleys aptly titled Hate and Death, while misunderstanding of another kind claims a quite different victim in Calvin Trillins sobering account of a Long Island murder case, The Color of Blood.

How crime spreads is the subject of Hanna Rosins sadly illuminating American Murder Mystery, a tale of good intentions gone disastrously awry. How crime can be thoughtlessly imported to our shores is the disturbing lesson to be taken from Matt McAllesters Tribal Wars.

The clever solving of a crime is the subject of David Granns fascinating account of a bizarre cold case in True Crime. However, a Sherlock Holmes approach has nothing to do with bringing down criminals in Alec Wilkinsons Non-Lethal Force, though as he makes clear, there is considerable intelligence behind the increasingly innovative technology of apprehending them alive.

A whole country destroyed by crime is the subject of Charles Bowdens harrowing Mexicos Red Days, while a crime that changed the world is brought to life again in Michael J. Mooneys The Day Kennedy Died.

These and other stories in this years The Best American Crime Reporting demonstrate that although crime itself may or may not pay, reading what the best of Americas writers have to say about it is profitable indeed.

We welcome submissions from any writer, editor, publisher, agent, or other interested party for The Best American Crime Reporting 2010. Please send the publication or a tear sheet with the name of the publication, the date on which the story ran, and contact information for the journalist or representative. If it first appeared in an electronic format, a hard copy must be submitted.

Only material first published in the 2009 calendar year is eligible. All submissions must be received no later than December 31, 2009. Anything received after that date will not be read. This is neither arrogant nor capricious. The timely nature of the book forces very tight deadlines that cannot be met if we receive articles later than that. The earlier material is received, the more favorable will be the light in which it is perused.

Please send submissions to: Otto Penzler, The Mysterious Bookshop, 58 Warren Street, New York, New York, 10007. Regretfully, no material can be returned. If you dont trust the postal service to actually deliver your submission, please enclose a self-addressed stamped postcard.

Thank you,

Otto Penzler and

Thomas H. Cook

New York, March 2009

I F ALL THESE CRIMES are so terrible, why do I feel so good?

Its not all murder in these pagesthere is a little fraud, robbery, and even (honest!) shopliftingbut most of the stories feature untimely demise, delivered by force. Some of the bodies are floating (an advertising executive in a river in Poland and a hedge fund manager in a pool near Palm Beach); some of them are mutilated (the victims of Mexican drug gangs and the corpses at a Philadelphia funeral home, sold to the transplant industry for parts); most are obscure (the victims of a Somali gang war in, of all places, Minnesota, and a loudmouthed punk on Long Island). One is very, very famous (JFK).

Still, these stories are the unlikely vectors of good cheer because, simply, they are so fascinating and so well told. These are good days for crime (most days are), but they are also rough days for journalism, especially for publications that tell stories at some length. Newspapers and magazines are going bust or shrinking, and so, it is said, are attention spans. But these stories show that narrative journalisma fancy term for story telling, nonfiction divisionis alive and well.

Notice that verb: show. As in the most venerable, and still the most useful, advice given to writers: show, dont tell. There is a wonderful moment in Hanna Rosins American Murder Mystery that brings home the meaning of that well-worn phrase. To be honest, the subject matter of Rosins story could sound a little dry. She is exploring whether the decision to close down high-rise housing projects for the poor and move their residents to suburban neighborhoodsa practice that was broadly supported across the political spectrumwas in fact good public policy. Rosin tells the story through a pair of husband-and-wife researchers in Memphis; by coincidence, he studies crime and she studies housing. One day, he decided to plot his violent crime statistics (in blue) over her poor people (in red). All of the dark-blue areas are covered in little red dots, like bursts of gunfire, Rosin writes. The rest of the city has almost no dots. Aha, says the reader, sharing the moment of recognition.

Its great reporting, which is the constant throughout these varied stories. In The Zankou Chicken Murders, Mark Arax recounts how Mardiros Iskenderian built a small empire of fast-food chicken restaurants in and around Los Angeles. There is family strife, and ultimately murder, but the key to the story for me was how delicious the food sounded. How did they make the chicken so tender and juicy? Arax asks. The answer was a simple rub of salt and not trusting the rotisserie to do all the work but raising and lowering the heat and shifting each bird as it cooked. What made the garlic paste so fluffy and white and piercing? That was a secret the family intended to keep. You could tell this story without dwelling on the food; a narrow-minded writer (or editor) could see it as extraneous to the crime story. But its not too much of a jump to see how the familys passion in the kitchen turned into rage of another kindat each other. Here, the mystery of the garlic paste mattered far more than the model of the handgun. (And the story made me want to kick myself, because I spent all those years in L.A. covering O.J. and I never tried this chicken! What was I thinking?)