THE GHOSTS OF EUROPE

ANNA PORTER

THE

GHOSTS

OF

EUROPE

Journeys Through Central Europes

Troubled Past and Uncertain Future

Copyright 2010 by Anna Porter

10 11 12 13 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver bc Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-515-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-637-1 (ebook)

Editing by Barbara Berson and Stephanie Fysh Jacket and text design by Jessica Sullivan Jacket photograph by Robert Capa 2001/Magnum Photos Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens Text printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer paper

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

FOR MARIA,

the keeper of memories

CONTENTS

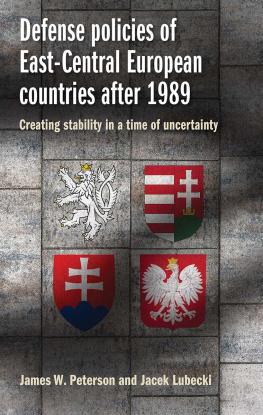

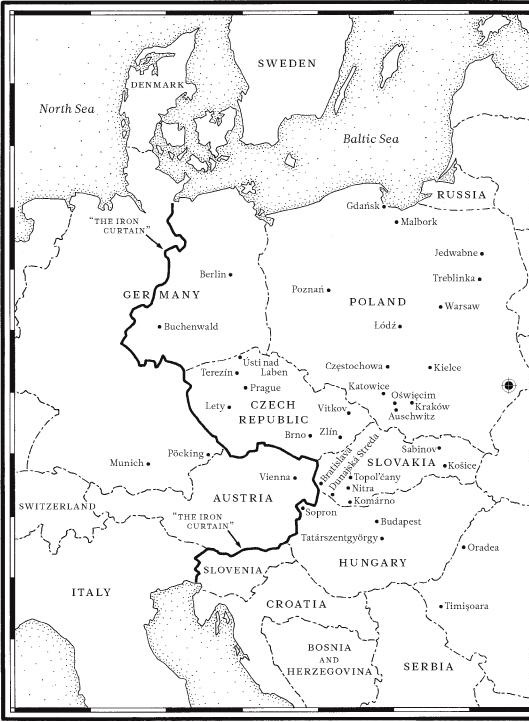

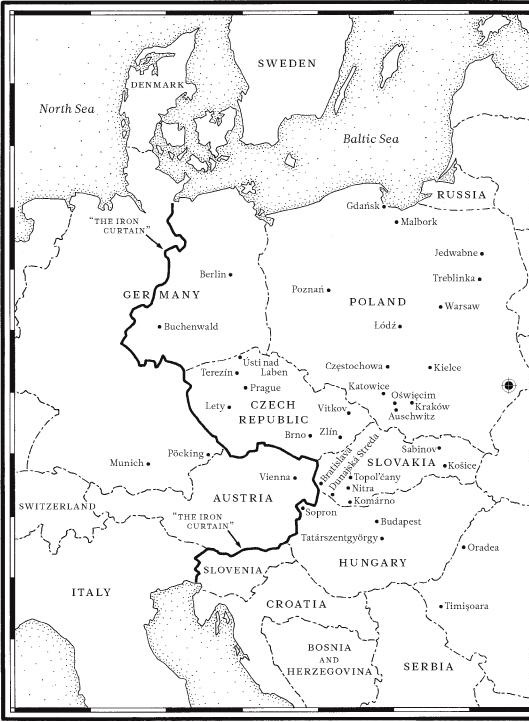

THE OTHER EUROPE

I N 1989, the Soviet Empire began to crumble and Central Europe, as local pundits and Western journalists were fond of saying, returned to history. Between 1946 and 1989, historians, journalists and politicians tended to dismiss these lands from discussion of Europe, as if they had somehow absented themselves from their own geography. Now the great cities of Warsaw and Budapest, Krakw and Prague, Bratislava and Vilnius would no longer be viewed as sitting stolidly on the far side of the Iron Curtains unfathomable chasm, a divide between us and them.

Poland was the first Soviet satellite to rebel against the hegemony of the Soviet Union, whose red czars, from Stalin to Chernenko, had provided their acolytes with the means to suppress opposition. In February 1989, the leaders of the formerly banned Solidarity trade union and the Communist Party leaders of Poland settled around a table to discuss how the country would recover from the human and economic disasters that the Partys rule had wrought. On June 4, 1989, Poland held the first semi-free elections in a Soviet satellite country.

On June 16, 1989, Hungarys former prime minister Imre Nagy, executed for his role during the ill-fated 1956 revolution, was reburied with the pomp and circumstance due a national leader. On July 6, he was formally rehabilitated by the Supreme Court. Thirteen days later, the last Communist prime minister of Hungary allowed several hundred East Germans free passage to the West. It was the first time since 1946 that East Europeans had been able to freely cross the Iron Curtain. When a reporter asked Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev whether he would like the Berlin Wall to be taken down, Gorbachev replied, Why not? Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Polands first non-Communist prime minister since 1947, took his seat in the Sejm (parliament) on August 24.

On October 18, Erich Honecker, the strongman of the East German Communist Party, stepped down.

On October 25, President Gorbachevs foreign ministry spokesman, Gennadi Gerasimov, voiced the end of Soviet hegemony over its satellites. When asked whether the Soviet Union would still follow the Brezhnev Doctrine of military intervention if needed, Gerasimov replied, in the spirit of the Frank Sinatra song My Way, So every country will decide in its own way which road to take. The implication was obvious: the Soviet Union would not come to the rescue of other Communist leaders. They were, as of now, on their own.

On November 9, the Berlin Wall was breached, peacefully. Amid breathless, televised jubilation, East and West Germans met and embraced over the divide that had, for twenty-eight years, seemed impenetrable. East German guards who only weeks before would have shot their fellow East Germans for attempting to escape to the other side were now dancing with West German girls and giggling with delight.

On December 10, when the new national unity government was announced, the Czechoslovak Communist Partyone of the most repressive regimes of the Soviet Blocgave up power.

During a mass meeting in Bucharest on December 21, 1989, the usually submissive Romanian crowd booed the Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and no one was arrested. When Ceausescu's shocked face appeared on national television, everyone knew that his reign was over. A few days later, he and his wife were arrested, tried by a military court and, on December 25, executed.

On New Years Day 1990, Vclav Havel, the new president of Czechoslovakia, stepped out on a balcony in Wenceslas Square and promised a government based on fairness and morality. He ended his speech with a quote from Tom Masaryk, the Czech politician and national hero who had successfully carved a country out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918: People, your government has returned to you.

In a move that would have been unthinkable a few months earlier, Havel welcomed world leaders to Prague. The list of dignitaries included President George H.W. Bush, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President Gorbachev, who said he grasped the opportunity for his own country to open up to democracy and for the world to escape from the threat of nuclear war. But, as Gorbachev saw it, the usa was not ready to deal with Russia as a partner, only as a defeated enemy.

At the end of 1989, there were 300,000 nuclear weapons equipped Soviet troops in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Four years later, they had all gone home.

When it was all over, and credit was claimed or assigned, there were many contenders: Ronald Reagan, who had challenged Mikhail Gorbachev to take down the Wall; Solidarity, the Polish trade union that refused to be intimidated; Pope John Paul II, the Polish pope, who defied the system and told people who opposed it not to be afraid; Germanys successful Ostpolitik, the effort to open the door between East and West; and Gorbachevs perestroika, or restructuring of the Soviet economy, and glasnost, or openness. Whether Gorbachev had a premonition about the future of his country and the rest of Europe or he was trying to reform Communism (as the general secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, Alexander Dubek, had done some twenty years previously) is still uncertain. Looking back, what is sure is that few in 1989 foresaw the events that ended the Communist era in Europe.

One might form the mistaken impression that the West was unified in its delight at the sight of all the walls collapsing. It was not. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, for one, aggressively opposed the unification of Germany. French president Franois Mitterrand worried about integrating the rebellious East into the orderly West. Americans, however, forgetting that some democratic elections have contributed to the worlds insecurity, imagined that the Wests export of democracy to the newly opened East would give them more security. The notion that democracy, like a commodity, is exportable is still prevalent among many Western politicians and continues to provide them with ample opportunities for disappointment. Unlike exotic fruit or fancy cars, democracy is best if it is grown locally. It may take root in the common desire of the people who choose to adopt it, but it cannot be imposed from the outside. While it has found fertile ground in most of the former Iron Curtain countries, it has not taken root in Iraq, and its Russian version excludes criticism of the government, as has been proven by the bodies of dead journalists.

Next page