Come to the woods, for here is rest. There is no repose like that of the green deep woods. Here grow the wallflower and the violet. The squirrel will come and sit upon your knee, the logcock will wake you in the morning. Sleep in forgetfulness of all ill.

Many lives are so empty of interest that their subject must first perform some feat like sailing alone around the world or climbing a hazardous peak in order to elevate himself above mere existence, and then, having created a life, to write about it.

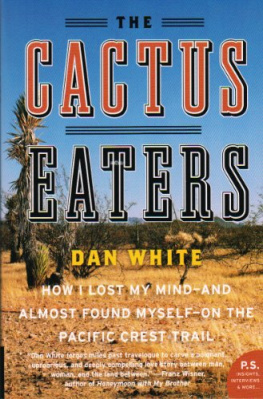

I ts 9:00 A.M . in the southern edge of the Sierra Nevada, eighty-five degrees and rising. The water in our bottles is almost gone, but I dont panic. I suck my tongue. I lick my hot teeth.

Allison, my girlfriend, stirs in her sleeping bag. She wakes up slowly, stretching her arms to the tents nylon roof. From the way she smiles at me, youd never know were in crisis mode again. Yesterday, our unbreakable leakproof water bag broke and leaked all over my $385 Gregory Robson backpack. Weve been rationing for fourteen hours now. I take a deep breath, try to stay calm, and smile back at her as best I can. Our love is still strong, in spite of the fact that Allisons hair is shagging into her eyes this morning, making her look like a yak, and in spite of the fact that we havent had sex in God knows how long. I emerge from our tent on my hands and knees and shake my boots for scorpions. There are none this morning. My socks are brown and hard and smell like ham. I put them on anyway. Allison puts on hers. Cowboy up, she says. She has splotches of dirt all over her body. Im not looking so great, either. After 178.3 miles and 2 1/2 weeks of this journey to the north, my shirt rots on my back. Pig bristles sprout from my chin.

We dust ourselves off and load our stuff into our backpacks. I walk out into the dry heat with Allison, my back pain, and the little bit of water weve saved. Five miles to go until we reach Yellow Jacket Spring. I am worried that the spring will not exist, or will have uranium or a dead cow in it. This morning I feel the strain of all weve seen and experienced: the heat blisters, the rashes, the dust devils, the coyotes who keep us up at night with their relentless whining. Still, things could be worse. At least were making progress. This, after all, is our dream, to be here in a real wilderness. I remind myself that were here by choice. We walk on. Beads of sweat draw paisley patterns through the dirt on my legs.

I watch Allison move through the landscape with confidence. Though shes dirty and tired, and in spite of whats happening to her hair, she is still lovely. She pouts in concentration as she studies the map and compass. Now shes passing me on the trail, edging around me, taking the recon position without consulting me. Is this an unspoken act of rebellion, I wonder? I walk behind her, and though I wish shed spoken to me about this leadership changeIm the designated leader for todayat least Ive got a nice view of her calves and her trail-hardened bottom as she leans forward to climb the hill, her hands on her shoulder straps. Her solar-reflective Outdoor Research survival hat shades her face. I try to forget my thirst, but I just cant. Every time I swallow, it feels like theres a Nerf ball in my throat.

The word Sierra conjures images of mountains, glaciers, rivers, and charming marmots. Scratch those pictures from your mind. Replace them with dust and dirt and sweat, canyon oak, pion pine, and in the middle distance, blunt-topped crags the shape and color of an old dogs teeth. Every once in a while theres a hint of darker colors: the slate-gray berries on a juniper bush, the black on the back of a turkey vulture below us in a canyon, but for the most part the scenery is pale beige, the color of stucco, the color of gefilte fish. The Pacific Crest Trail is renowned for its beauty, but this patch of trail is plug-ugly, and we havent seen a human in five days. We walk downhill along an abandoned jeep road to search for the spring. Every once in a while the top of a pion pine peeks from behind a stack of boulders. A mirage appears in a bend on the road. Pools of quicksilver fade as we approach. After fifteen minutes, the dirt road levels, then turns uphill on a punishing grade. Im starting to wonder why we havent found the water. It seems weve gone far enough. Im starting to worry that the spring has dried up.

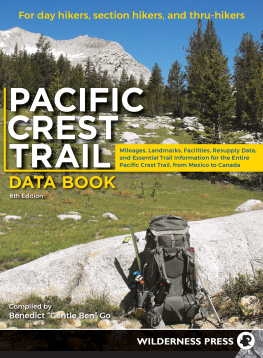

To distract myself, I remember how we boasted about the trail to everyone who would listen. Even Patrick, my swordfish-nosed barber, knows all about it. Allison and I ditched our jobs in Torrington, Connecticut, to walk the Pacific Crest Trail, a 3-to-10-feet-wide, 2,650-mile-long strip of dirt, mud, snow, ice, and gravel running from Mexico to Canada. The trail starts at the Mexico-California border town of Campo, buzzing with border patrol guards in helicopters. It climbs the Laguna, San Jacinto, and San Bernardino ranges, drops to the Joshua trees and hot sands of the western Mojave Desert, and rises close to the base of Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the lower forty-eight states. The trail nears the thermal stench pots, fumaroles, boiling lakes, and gassy geysers of Lassen. Then it pushes through the Columbia River Gorge and into the North Cascades before coming to a stop in Manning Park, British Columbia. The trail spans California, Oregon, and Washington. On the PCT, you pass through state and federal lands, sovereign Native American territory and timber holdings. You see a thousand lakes, and travel through seven national parks. In the northern lands, mountain goats scale hundred-foot walls in seconds flat. Reach out your hand and you can grab a fistful of huckleberries right off the bush. In northern streams, river otters splash in the shallows.

The PCT is Americas loveliest long-distance hiking path, but the trail exacts a toll for a glimpse of its pretty places. In some areas, you must find your way amid the firebreaks and game trails that slither off in all directions like the fever dreams of a serial killer. Ticks, in chaparral lowlands, will crawl onto hikers and bite them in the armpits and groin. Walkers whip off their clothes to find forty or fifty of them at once, looking like M&Ms with legs. More than 50 percent of the people who walk the trail give up in despair, often within the first week. The route has existed in various forms for more than forty years, and in that time, roughly a thousand people have hiked it all. Thats fewer than the number of people who have stood atop Mount Everest.

The trail ranges from just above sea level to 13,180 feet. It twists through lands where surface temperatures creep past a hundred degrees, and up into terrain that is snowbound for most of the year. Pacific Crest Trail hikers must time their walks perfectly. If they start too early, they find themselves marooned like Ernest Shackleton, hacking at snow walls with their ice axes. If they start too late, the Mojave toasts them in their boots. Even if they make it through the desert, snowstorms will slam them in the Cascades, sometimes in early September. Unfortunately for Allison and me, we couldnt get out of Connecticut until June. Now its almost July and the landscape is set on broil. Its empty here. Most hikers passed through these lands six weeks ago. Allison walks beside me now, her footsteps faster and more insistent. Why, she says, is it so fucking hard to get a drink around here?