Table of Contents

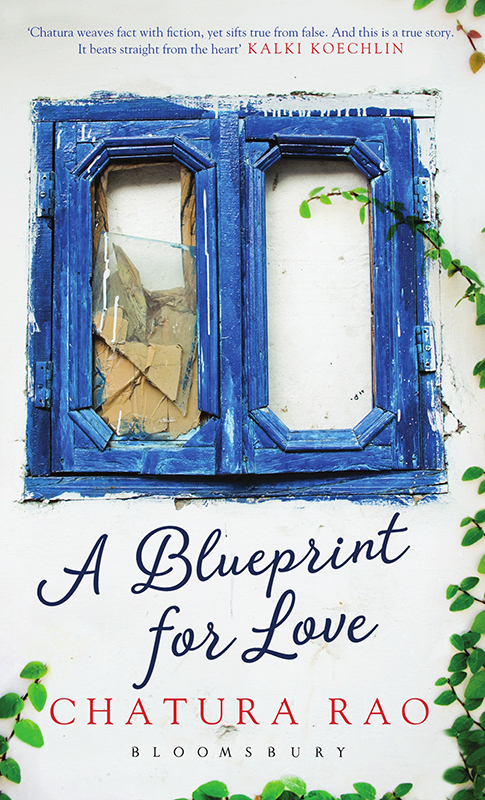

A BLUEPRINT

FOR LOVE

Chatura Rao

First published in India 2016

2016 by Chatura Rao

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

The content of this book is the sole expression and opinion of its author, and not of the publisher. The publisher in no manner is liable for any opinion or views expressed by the author. While best efforts have been made in preparing this book, the publisher makes no representations or warranties of any kind and assumes no liabilities of any kind with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the content and specifically disclaims any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness of use for a particular purpose.

The publisher believes that the content of this book does not violate any existing copyright/intellectual property of others in any manner whatsoever. However, in case any source has not been duly attributed, the publisher may be notified in writing for necessary action.

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

E-ISBN 978 93 86250 03 2

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No. 4

DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7, Vasant Kunj

New Delhi 110070

www.bloomsbury.com

Created by Manipal Digital Systems.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

For my parents

Nothing has changed.

Except for the course of rivers,

the lines of forests, coasts, deserts and glaciers.

Amid those landscapes roams the soul,

disappears, returns, draws nearer, moves away,

a stranger to itself, elusive,

now sure, now uncertain of its own existence,

while the body is and is and is

and has nowhere to go.

from Tortures by Wislawa Szymborska

Contents

On Thu, Oct 22, 2015 at 11:47 AM, Suveer Bisht <> wrote:

I looked up Google maps and found, midway between you and me, Nashik in Maharashtra. Were lucky that Abolis birthday arrives in November (every year, unfailingly  ). Fairly pleasant weather to travel. Let me know if you can make it. Ill meet you at the station.

). Fairly pleasant weather to travel. Let me know if you can make it. Ill meet you at the station.

Suveer

P. S. After the 17th I have an interesting assignment in Gujarat. Ill tell you about it when we meet.

On Thu, Oct 22, 2015 at 10:23 PM, Reva Amre <> wrote:

Ive asked my boss for the 3rd and 4th of November off. Ill bring a small plum cake, Abolis favourite (you know!) and a candle to light. She would have turned 34 this year, but one candle will have to be enough.

Looking forward,

Reva

When they were little girls Reva and Aboli had lived on the tenth lane off Prabhat Road, Pune, in a cream house with a red floor. Its two storeys were flanked with wide verandahs, the rooms large and high-ceilinged.

For Reva even now the house was like a cupboard that wouldnt close. She tried to spring-clean her memories, with a light heart whenever possible, arranging the odds and ends, patting them down and shutting firmly the old doors. She would wedge remembered conversations like folded pieces of paper between them. Yet ragtag shadows and sounds spilled out. Impressions that were nearly three decades old still called to her in her bed next to Tarun, sometimes travelling on a local train, or sitting on a beach in Mumbai, the city she now called home.

When Abolis sister, her cousin Sharada, called up to say hello, Reva would put aside whatever she was doing to listen carefully to news about the family in Pune. Shed ask for every last detail. Their words rode on currents of shared history like Abolis hand-me-downs in whose pockets shed find clues, forgotten treasures, a bead perhaps or a button. They were auguries to her of the fine line her family trod between the possibilities of the present and the disasters of tomorrow.

Outside the front door of their house was a long, wide staircase that lent itself to a good game of Simon Says. When the den, one of her brothers or sisters called out Simon Says, go in, shed run through the verandah and step through the white-painted wooden doors.

Once in, the hall opened into large rooms with windows that were high and narrow. Mango and country almond trees sifted in patches of light like diamonds on a card pack. Within, they played cards at the night-long vigils of Janmashtami: games of Donkey, Rummy and Bluff, blue light on their plotting heads, rounded shadows on their crossed legs.

To get to the ground floor from the first, theyd slide down the smooth cement banister that ran along the stairs. The bigger fellows landed on their feet with a triumphant bounce. Reva mostly tumbled into a clumsy squat halfway down.

Once when she was eight, the oldest of her cousins, 14-year-old Sharada, concocted lime juice right in her trusting mouth. First Sharada had poured water in and then spiked it with lemon cordial. Reva stood there, gasping and crying, mouth agape, not knowing whether to spit or to swallow. Aboli at twelve had no such problems. She walked into the kitchen, sized up the situation, placed her hands on Revas shoulders and steered her to the back door.

Spit! shed said.

Reva still remembered the sudden spread of lemonade on mud, and her own indignant tears, Sharadas peals of laughter and Aboli urging her away upstairs to her special place the doll cupboard.

It was stuffed with old and new baby dolls. Each doll had a name and whenever Aboli invited any of the children to play, theyd sit for hours combing back their straggly hair and applying their mothers talcum powder on their necks. Crooning over a baby doll, Reva smiled again. And Aboli skipped away, planning revenge on Sharada.

Aboli and Sharadas father, Manohar Amre, was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom lived with their parents and families in the bungalow on Prabhat Road. Or at least they had, until the death of Reva and Abolis paternal grandmother.

Shortly after, the familys daughters-in-law wanted their own kitchens and to raise their children as they willed. When a part of the familys wholesale cloth business was sold, with the proceeds the three younger Amre brothers could afford to move. They departed, one by one, taking their wives and children to live in two-bedroom apartments. The children now had to make do with their siblings, but met every month for raucous family get-togethers at the Prabhat Road house and occasionally for long drives to the nearby hill stations of Lonavla and Khandala.

Aboli and Sharada stayed on in the old house with their parents and grandfather. It was a house too large for five people, and often, Aboli told Reva, she heard ghost voices of earlier times and louder games echoing in the large rooms. The house, spare and utilitarian while their grandmother was alive, began to fill up with ornate sofas, brass lamps and traditional paintings as Abolis mothers taste took over.

). Fairly pleasant weather to travel. Let me know if you can make it. Ill meet you at the station.

). Fairly pleasant weather to travel. Let me know if you can make it. Ill meet you at the station.