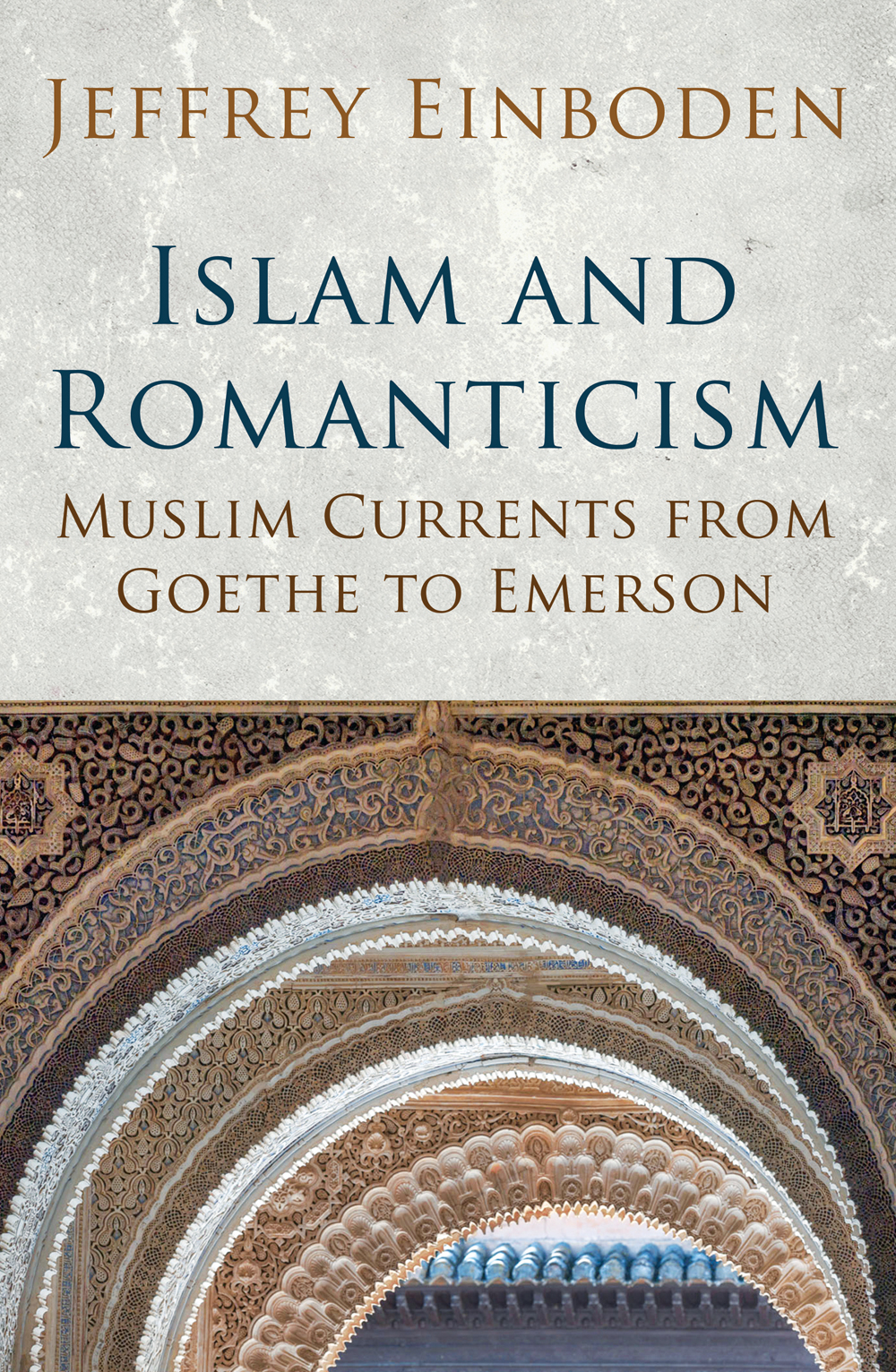

ISLAM AND ROMANTICISM

m uslim c urrents from g oethe to e merson

ISLAM AND ROMANTICISM

m uslim c urrents from g oethe to e merson

Jeffrey Einboden

Muslim and Islamic Contributions to Culture and Civilization

Series Editor:

Todd Lawson

A Oneworld book

Published by Oneworld Publications 2014

This ebook edition first published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright Jeffrey Einboden 2014

The right of Jeffrey Einboden to be identified as the

Author of this work has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781780745664

eBook ISBN 9781780745671

Typeset by Jayvee, Trivandrum, India

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR, England

Contents

C harting intersections between Western literature and Muslim sources, Islam and Romanticism reaches back to my earliest scholarly efforts, and thus reflects a decade of intellectual debts. At the University of Cambridge, I thank Tamara Follini and Douglas Hedley, who first planted the seeds for such a study. Formative too was my participation in 2004 at a conference hosted by Uppsala University an opportunity, like so many others, that I owe to Bernie Zelechow. I thank Annabella Dietz for graciously welcoming my 2007 visit to Schloss Hainfeld, Hammer-Purgstalls Austrian estate. The actual writing of Islam and Romanticism was first suggested by Todd Lawson, the editor of Oneworlds monograph series, Muslim and Islamic Contributions to Culture and Civilization. I am grateful for Todds invitation to contribute to the series, and his generous encouragement of my scholarship more broadly. At the press, I also wish to thank Oneworlds excellent editors and readers, and most especially, Novin Doostdar and James Magniac, as well as all those who reviewed and commented on the book, entirely or in part, including Todd Lawson and James Vigus; any errors that remain are solely my own.

The book received essential aid from Northern Illinois University, including a 20122013 sabbatical, and years of previous support from the Universitys Graduate School. I have been favored with exceptional colleagues and friends at NIU, whose advice and advocacy have proved pivotal. I thank, in particular, Betty Birner, Lara Crowley, Tim Crowley, James R. Giles, Ryan Hibbett, William C. Johnson, Amy Levin, Jessica Reyman, Luz Van Cromphout, and Mark Van Wienen. During the final months of writing Islam and Romanticism , my research received inspiration and assistance too from the Boston Athenaeum; I am especially grateful to the superlative curators, librarians, and staff who made my 2013 fellowship at the Athenaeum so memorable. I thank too the National Endowment for the Humanities for its support of projects that parallel the present book, funding my research into U.S. Arabic slave writings (20112012), as well as Islamic literacy in early America (2014).

I am grateful to the journals which first featured my research into Romantic receptions of Muslim sources, and which now informs the present book. In particular, I acknowledge Literature and Theology , which published my The Genesis of Weltliteratur : Goethes West-stlicher Divan and Kerygmatic Pluralism in 2005 (selections from which appear, or are expanded upon, in Chapters 1, 5, and 6); and the Journal of Quranic Studies , which published my The Early American Quran: Islamic Scripture and US Canon in 2009 (selections from which appear, or are expanded upon, in Chapters 14, 15, and 16).

My writing of Islam and Romanticism received vital encouragement from my family, most especially Becky, Steve, Avery, Josh, and Rachel; Shelley and Mike; Syd and Lily; as well as from life-long friends, Andrew, Brad, James, Matthew, and Richard. As all my endeavors, this book would have been inconceivable without the inspiration of my parents Pam and Ed and the love and laughter of my wife and son Hillary and Ezra. With a gratitude that remains inexpressible, this book is dedicated to them.

On July 12, 2000, the President of Germany and the President of Iran met in Weimar, convening over two chairs. Neither an international summit, nor a bilateral conference, this encounter between President Johannes Rau and President Muhammad Khatami was instead occasioned by the two chairs themselves. Erected at the heart of Germanys capital of culture, these simple seats merited such global attention as they form the Goethe-Hafis Denkmal the Goethe-Hafiz Memorial a UNESCO site commemorating the pivotal exchange between the national poets of Germany and Iran: Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Mu ammad Shamsudd n fi (Figure s 1 and 2, below).

A concrete reminder of Islamic contributions to Western art and expression, the Goethe-Hafis Denkmal seems, on first view, a rather stark and imposing reminder, its grey vertical chairs rising up in unadorned stone. It is the chairs horizontal base, however, that hints at a more rich and nuanced relationship, inscribed with scattered quotations in Persian and German, voicing a lyric dialogue between these writers of world renown. Featured in this floor space between the chairs is a Persian ghazal excerpted from fi s beloved Divan his celebrated poetry collection a masterpiece of mystical artistry which was posthumously assembled, surfacing in the years that followed fi s death (c. 1390 ce ). The flowing script of this Persian poem is surrounded by more angular lines of German, reproducing verses

Figure 1 Goethe-Hafiz Memorial , Beethovenplatz, Weimar, Germany. Authors photo.

Figure 2 Goethe-Hafiz Memorial , base inscribed with Goethes poetry. Authors photo.

authored by the aged Goethe, exemplifying a late period in his career when he was deeply impressed by fi a period that would culminate in Goethes own Divan , his 1819 West-stlicher Divan ( West-Eastern Poetry Collection ).

A meeting of dual divan s not only two chairs ( divans ), but also two poetry collections ( Divans ) Weimars memorial is built solidly upon diverse languages and distinct literatures, rising from ground that is culturally double, equally German and Persian. It is not a dichotomy of culture, however, but a dichotomy of country and continent that seems most urgently implied in these confronting chairs. Situated in opposition , these vacant seats suggest a physical separation between West and East, even as they face each other in mutuality; recalling the very title of Goethes West-Eastern poetry collection, the Weimar memorial embodies not only geographic distance between Occident and Orient, but also their inescapable encounter. Complementing this spatial distance is the temporal divide which seems more subtly suggested in these chairs, the gap between the two seats mimicking the historical gap that intervenes between fi in the fourteenth century and Goethe in the nineteenth century, both connecting and contrasting the medieval and the modern.

_fmt.jpeg)

_fmt.jpeg)