Copyright 2005 by Donald Kroodsma

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Kroodsma, Donald E.

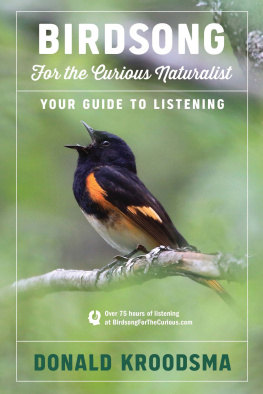

The singing life of birds : the art and science of listening to birdsong / Donald E. Kroodsma.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

ISBN 0-618-40568-2

1. Birdsongs. I. Title.

QL698.5.K76 2005

598.159'4dc22 2004065130

e ISBN 978-0-547-34487-4

v1.0215

Maps by Nancy Haver and Mary Reilly

Ripleys Believe It or Not 2013 Ripley Entertainment Inc.

F OR M ELISSA

The earth has music for those who listen.

William Shakespeare

Preface

S OMEWHERE, ALWAYS , the sun is rising, and somewhere, always, the birds are singing. As spring and summer oscillate between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, so, too, does this singing planet pour forth song, like a giant player piano, in the north, then the south, and back again, as it has now for the 150 million years since the first birds appeared.

Ten thousand species strong, their voices and styles are as diverse as they are delightful. Some species learn their songs, just as we humans learn to speak, but others seem to leave nothing to chance, encoding the details of songs in nucleotide sequences in the DNA. Of those that learn, some do so only early in life, some throughout life; some from fathers, some from eventual neighbors after leaving home; some only from their own kind, some mimicking other species as well. Some species sing in dialects, others not. It is mostly he who sings, but she sometimes does, too. Some songs are proclaimed from the treetops, others whispered in the bushes; some ramble for minutes on end, others are offered in just a split second. Some birds have thousands of different songs, some only one, and some even none. Some sing all day, some all night. Some are pleasing to our ears, and some not.

It is this diversity that I celebrate. How the sounds of these species differ from each other is the first step to appreciating them, of course, but those questions quickly give way to why questions. Why do some learn and others not? Why do dialects occur in some species and not others? Why is it mainly the male who sings? It is these and similar why questions that so intrigue us biologists as we try to understand the individual voices that contribute to the avian chorus.

In writing about our singing planet, I can focus on only a few of its voices. The thirty stories told here are personal journeys, ones that I have traveled over the past thirty years in my quest to understand the singing bird.

Many are based on my own research and are years in the making. Others are based on just several days experience, or even less, as I seek out birds that illustrate the research of friends and colleagues who share my passions. No matter the source, each story is based on listening and on learning how to hear an individual bird use its sounds, and each story illustrates some of the fundamentals of the science called avian bioacoustics. Together, I hope these stories and their sounds reveal how to listen, the meaning in the music, and why we should care.

Acknowledgments

S O MANY PEOPLE play a role in putting together a lifes passion. I thank my parents, Margaret and Dick Kroodsma, for letting me grow up in the middle of nowhere, the out-of-doors everywhere to explore; Olin Sewall Pettingill, Jr., for first putting a tape recorder, parabola, and headphones into my hands; John Wiens and Peter Marler, graduate and postgraduate advisors, for providing the freedom to play; graduate and undergraduate students who have worked with me at the University of Massachusetts, for fueling a contagious enthusiasm for understanding birds and their songs; and countless other enthusiasts, both professional and amateur, who have shared this passion to know birds and their sounds.

I am indebted to a number of people who helped in various ways with this book. Curt Adkisson, Mike Baker, Russ Balda, the late Luis Baptista, Jon Barlow, Greg Budney, Chris Hill, Steve Hopp, Curtis Marantz, the late Frank McKinney, Gene Morton, Gary Ritchison, and Philip Stoddard all shared their top ten lists of North American bird sounds. Tape-recordings from several friends were indispensable in preparing the CD: Mike Baker, Greg Budney, Lang Elliott (www.naturesound.com), Hernn Fandio, Will Hershberger, Geoff Keller, Randy Little, Steve Pantle, and a number of others who are acknowledged with the CD. Others offered advice or other kinds of help: Mike Beecher, Bruce Byers, Russ Charif, Cal Cink, Terry Doyle, Peter Elbow, Sylvia Halkin, Chris Hill, Peter Houlihan, Steve Johnson, Carrie Jones-Birch, Geoff LeBaron, Wan-chun Liu, Curtis Marantz, Gene Morton, Jan Ortiz, Bert Pooth, Haleya Priest, Don Stap, Dave Stemple, Scott Surner, Jane Yolen, and Bill Zimmerman. Many others have contributed, too, either directly or indirectly, to the stories told here: I thank the chickadee enthusiasts who stormed Marthas Vineyard with me, for example; those who have helped reveal the bellbirds secrets; Julio Sanchez, for his love of birds and Costa Rica; and so many others with whom I have shared this birdsong journey (thanks, Judy Wells and Roberta Pickert). Im particularly grateful to Casey Clark, David Spector, and Mary Alice Wilson for reading and trouble-shooting the entire manuscript. And thank you, Nancy Haver, for your wonderful drawings that illustrate the text.

I especially thank the crew at the Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology for their generous and expert help in putting the CD together: Bob Grotke, Steve Pantle, Mary Guthrie, Carol Bloomgarden, Jack Bradbury, and especially Viviana Caro, for her patience and skill in getting it all just right. I owe enormous thanks to Greg Budney, tireless friend and birdsong enthusiast, for making so many good things happen.

For the encouragement to write, and continue writing, I thank Pat Schneider and friends at Amherst Writers and Artists; the guys, meaning Bob, Carl, Deene, Fred, Larry, and Mike; my mother-in-law, Linda Parker; and especially my wife, Melissa, who was a partner in much of the research and worked hard to provide the time to get the writing done.

For seeing the potential in an unpolished manuscript, I thank Russ Galen, and for their guidance and expertise in the polishing, I thank Lisa White and Anne Chalmers at Houghton Mifflin.

Not least, for just being there and singing, I thank the birds themselves.

Beginnings

G ETTING STARTED is always a challenge, not only for the research scientist but also for anyone who would simply listen to birdsongs. In the first section of this chapter, I share my secret for listening: Its all in the eyes. Seeing bird sounds as we hear them greatly helps us appreciate the details in the sounds and the differences among them.

In the second section, I share my personal beginnings as a scientist, as I tell of my quest for understanding how a young male songbird, a Bewicks wren, gets his song. After two years of hard work and good fortune, I found not only the answer to my simple question but also a lifelong passion. In the process, I also learned how to listen.

Next, for those who wish to learn how to listen, the American robin in the backyard provides ample opportunity. Anyone truly listening to a robin will begin to hear details once thought impossible. Listening to robins also prepares one for other adventures, such as identifying all of those robin sound-alikes, hearing the details in how all birds sing, and asking and answering questions of all kinds (that is, doing science) by oneself.

Next page