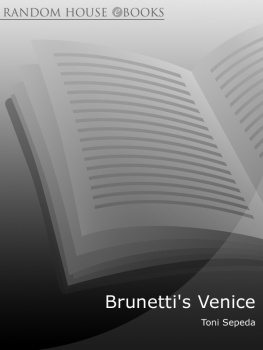

BRUNETTIS VENICE

BRUNETTIS VENICE

Walks with the Citys Best-Loved Detective

Toni Sepeda

With an Introduction by Donna Leon

Copyright 2008 by Toni Sepeda and Diogenes Verlag AG, Zurich

Introduction copyright 2008 by Donna Leon and Diogenes Verlag AG, Zurich

Copyright 2008 for all the maps to the twelve city tours by Falk Verlag D-Ostfildern

Copyright 2008 for the lagoon map by Laguna Veneta, Edizione Garbizza, Castello 5314, 30122 Venezia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Originally published in German in 2008 by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zurich First published in English in 2009 by William Heinemann, Random House, London

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9984-3

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

Contents

Introduction by Donna Leon

I first became aware of how little, and how badly, I knew Venice about thirty years ago, when I was invited to dinner at the home of friends of friends. Id been there for dinner a number of times, but Id always gone in the company of my friends Roberta and Franco, trailing along as the foreign guest. They, Venetian for generations, led the way, and I walked along with them, listening, learning Italian and a bit of Veneziano as we walked. I heard the names of their friends, picked up vocabulary, greeted the relatives and colleagues we passed on the street, stopped to have a coffee, was advised which shops to use and which to avoid.

Every trip with them had been a discovery as well as a bombardment of information. Because they led the way, I didnt have to be bothered with boring details like where to turn left or where to turn right: I merely followed the leader. They were the sharks, I the pilot fish following in their wake.

This time, however, and for reasons I no longer recall, I had to get there on my own. And couldnt. The host lived, I knew, over near San Giacomo dellOrio, down on the right of that little calle that ran into the canal, almost at the end. Further, I knew that Francos father, during World War II, had once fallen into the laguna when he went fishing with a man who lived on the second floor of the house opposite the apartment I was looking for.

Unfortunately for my purposes, the dinner began at 8:30, so it was dark when I walked through Rialto, on the way to what I was sure was the campo. Map? Me? I wasnt a tourist, was I, so why would I bother with a map? I was the friend of Venetians, on the way to dinner at the home of other Venetians, so why a map?

A half-hour later, I stumbled upon Campo San Giacomo dellOrio and began to look for the little calle that ran down towards the canal, the one where lived the man who... etc. etc. etc. They all looked alike. Even if I had had a map, I had no idea of the name of the calle, and I doubt that any map I might have carried would have marked the address of the man who was with Francos father when he fell into the laguna.

Finally I went back to the campo and asked in a bar where Giuliano the jeweller lived. When I finally arrived, I lied of course about the delay and we got on with the serious business of drinking and eating.

Because I did not grow up in Venice, I lacked the imprinting of calli, campielli e canali that is part of the Venetian heritage. It comes of walking there and walking back home and walking to the other place, and walking back home; hundreds of times, every day for decades. Thats how the city goes into the memory. Along with that comes the more personal and colourful part: the stories of people falling into the laguna, the story about the house where the butchers wife went to live when she ran off with the shoemaker; the shop that used to sell the best stracchino in the city before it became a real estate office.

There is the majestic history of the city: the Doges and the Battle of Lepanto and Daniele Manin and Paolo Sarpi, a victim of the Inquisition. There is the memory of the Serenissima and its trading empire; there are the painters and the architects and the endless line of composers.

But there is also a different, more personal, history, and my experience of the city is that many people use this as the basis for their geography. Take, for example, Il Ponte dei Giocattoli, the bridge of the toys. It stands at the end of the street that leads from Rialto, past Coin, to Campo Santi Apostoli, and that is the name it has had for at least fifty years: Ponte dei Giocattoli. But the toy store, at the bottom of the bridge that still bears its name, is an ex-toy store now and sells shoes. Venetians, however, still call it Il Ponte dei Giocattoli, and probably will for many decades. As they still call it Calle dei Fabbri, though there are no more fabbri, and Calle del Cafetier might not any longer be a place where coffee beans are roasted.

How dull, a street with a number for a name.

As I imagine him, Brunetti is a man whose sense of the city was fashioned in this way. He grew up here, speaking Veneziano at home, listening to his parents and relatives and their friends tell stories about the way the city was when they were younger. He went to school here, walking home for lunch and returning to class until he finished university; walking across the city to visit or study with his friends and walking to meet his first girlfriends to walk again to a cinema or a party or to a boat that would take them to Lido or to one of the islands.

This instinctive sense of the city is acquired only by those who grew up here or who have lived here for decades and, by force of repetition, have had the city program itself into their feet. Those who come to Venice as visitors must hope to find a Venetian friend who will guide them through the narrow streets, explaining a bit of history here, a story from his youth there, perhaps grumbling about the tourists, occasionally pausing for un ombra.

Brunettis Venice does those things, for it allows the reader to move through the city in the company of a Venetian who has, over the course of years, become a friend. Because he is Venetian, Brunetti does not have to give conscious thought to taking the correct left turn or finding the proper calle. His memory is filled with the legends and lies that have accumulated around places and events for the last thousand years, and it is those things which often fill his mind as he walks through the city, not the need to check the map to see that the second turn on the left is the one to take. Much as he might be distracted, he never gets lost.

The book accompanies Brunetti through the various sestieri and records his emotional, as well as his visual, response to the places he has known all his life. Loyal to San Polo, where he now lives, he still cannot remove Castello from his heart, for it was there he spent much of his youth. Whenever he has to go to San Marco, his awareness of the presence of so much well-hidden wealth causes him a vague uneasiness, no matter how much he might try to dismiss it, though this uneasiness never succeeds in dulling his powerful response to the lavish beauty on offer. Giudecca is Patagonia: after all, his parents and their friends called it

Next page