About the Author

Toni Sepeda has been teaching literature and art history at the University of Maryland European Division for more than twenty years. Besides co-authoring an American guide to Venice and the Veneto, she has written a memoir of building a house on the Black Sea coast of Turkey, recently the subject of a CNN documentary. She also gives privately arranged tours through Commissario Brunettis home city the only tours authorized by Donna Leon. Her latest university lecture series is dedicated to Brunettis Venice.

About the Book

Visitors to Venice might hope to find a Venetian friend who will guide them through the narrow streets, explaining a bit of history here, a story from his youth there, perhaps grumbling about the tourists, occasionally stopping for a glass of prosecco or to gossip with friends

Brunettis Venice does all these things as it moves through the famous city with Commissario Guido Brunetti, the much loved Venetian detective of Donna Leons bestselling novels. Presented as a series of walks through Venice and featuring atmospheric extracts from relevant parts of the novels, it is woven together by a commentary that links Brunettis emotional and visual responses to places he has known all his life with the inquisitiveness of the visitor.

The first walk starts at La Fenice Opera house where the very first Brunetti novel began and ends at the iconic Rialto Bridge. Each consequent route weaves interlinking paths through Venice and catches the secrets, sounds, sights and smells of Venice past and present. Along the way we visit Brunettis favourite eateries around the Rialto bridge, walk with him from his home in San Polo to the Questura in Castello where he works, cut through Piazza San Marco and accompany him on the vaporetti out to more remote parts of Venice. There are reflections on the art and architecture of Venice, as well as the impressions of writers from Shakespeare and Goethe to Thomas Mann and Jan Morris.

Enchanting and practically useful, Brunettis Venice is both a walking guide and an evocative narrative of the life of this most magical city for any Brunetti fan.

Brunettis Lagoon Islands

San MicheleMuranoBuranoLe VignoleLidoSan ServoloPellestrina

you should choose the finest day in the month and have yourself rowed far away across the lagoon to Torcello. Without making this excursion you can hardly pretend to know Venice.

Henry James, An Early Impression

in Italian Hours

AFTER A DOZEN walks through the city of Venice with Commissario Guido Brunetti, it is time to enter another part of his world, the islands of the laguna. The Venetian lagoon has always shared the citys Janus-faced reputation: a suspicious remoteness for residents; a romantic, mysterious allure for foreigners. Goethe crossed the laguna to claim in his Italian Journey, Now, at last, I have seen the sea with my own eyes. Shelley immortalized the lagoon floating with funereal gondolas, while Ruskin later cursed its dirty steam-engines. Byron swam across it from the Lido to the Grand Canal; James made a journey through it a required adventure for any visitor. Manns Aschenbach died on the Lido; Diaghilev, Stravinsky, Ezra Pound, and Joseph Brodsky are all buried on Isola San Michele.

Rather than a specific walk, this chapter journeys through the laguna to and past the islands used by Donna Leon in the Brunetti novels: from the cemetery island of San Michele, where Brunettis father is buried, to Murano, the setting for Through a Glass, Darkly, to the Lido for The Death of Faith, and finally further south to Pellestrina and A Sea of Troubles. Brunetti has fewer of the familiar wide-ranging walks he takes in the other novels. Instead, he repeatedly finds himself a stranger in the laguna, constantly interpreting codes and manners far different from those of his world in Venice.

* * *

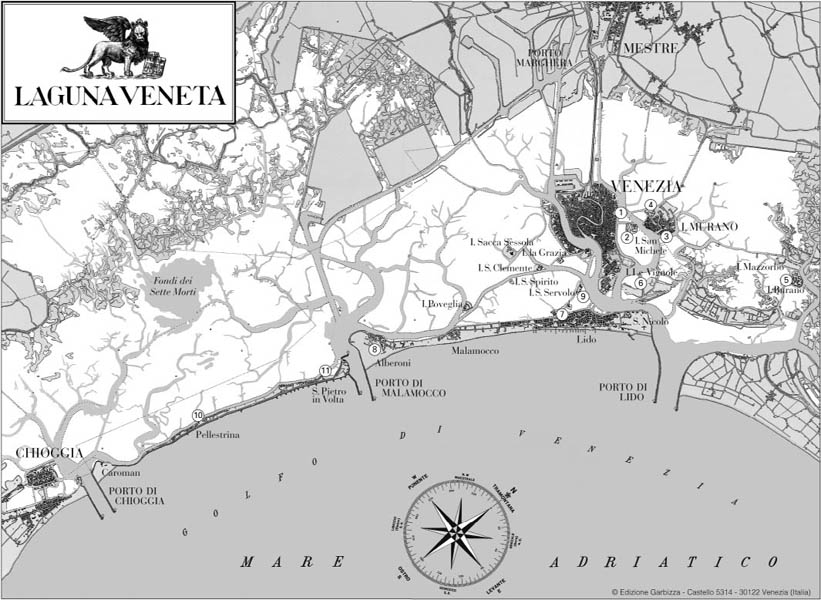

Nowhere is the Venetians ambivalent attitude to their laguna more apparent than when Brunetti faces his utter ignorance of the locations of any but the most familiar islands, the arrangement of the various canals, the regions where his seafood meals originate. Never a boatman, he ponders a map of Venices waters in total bewilderment that he should live in the centre of so mysterious a body of waters the palude.

He dropped the other maps back into the box and took the map of the laguna out on to the terrace. Careful of the long-dried tape that held parts of it together, he opened it slowly and stretched it out on the table. How tiny the islands looked, surrounded by the vast expanse of palude. For kilometres in every direction, the capillaries and veins of the channels spread, pumping water in and out twice a day, as regular as the moon itself. For a thousand years, those few canals at Chioggia, Malamocco and San Nicol had served as aortas, keeping the waters clean, even at the height of the Serenissimas power, when hundreds of thousands of people had lived there, their waste added to the waters every day. ()

The immensity of the area depicted on the map reminded him how lost he was in it and how ignorant of how things were organized upon its waters, even in relation to the jurisdiction of crimes. If cases were given out, rather in the manner of party favours, to the first comer, then how could one expect to find consistent records of what had happened there?

He assumed that large fish were taken from the Adriatic; where then did the clams and shrimp come from? He had no idea what places in the laguna could legitimately be used for fishing, though he assumed that all of the shallow waters lying just off the coast of Marghera would be closed. Yet if what the boat pilot said, and Vianello believed, was true, then even that area was still fished. (A Sea of Troubles, ch. 13)

SOLA di SAN MICHELE (2)

Boating into the laguna from the most popular departure point, Fondamenta Nuove (1), the first sight, and the last truly familiar place for Venetians, is the cemetery island of San Michele surrounded by towering cypresses. Although Brunetti rarely goes simply to visit, not having acquired the cult of the dead so common among Italians, as he says in Death in La Fenice, he is pulled to the island for occasional autopsies. The grimness that accompanies Brunetti on his walks to the Ospedale Civile in Campo SS Giovanni e Paolo to attend to victims or identify bodies is made more acute when a watery journey out to the cemetery island is required. In Death in a Strange Country, a medical doctor from the nearby American Army base at Vicenza has arrived at Piazzale Roma to identify the corpse of the young sergeant found floating in a Venetian canal. Her sombre appearance and youth, added to her unawareness of where the body has been taken, makes his task more painful.

Without bothering to say goodbye to the men inside, Brunetti left the station and went towards the car. Doctor Peters? he said as he approached.

She looked up at the sound of her name and took a step towards him. As he came up, she held out her hand and shook his briefly. She appeared to be in her late twenties, with curly dark brown hair that pushed back against the pressure of her hat. Her eyes were chestnut, her skin still brown from a summer tan. Had she smiled, she would have been even prettier. Instead, she looked at him directly, mouth pulled into a tense straight line, and asked, Are you the police inspector?

Commissario Brunetti. I have a boat here. It will take us out to San Michele. Seeing her confusion, he explained, The cemetery island. The bodys been taken there. (