Foreword copyright 2016 by David W. Blight and Robert B. Stepto

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

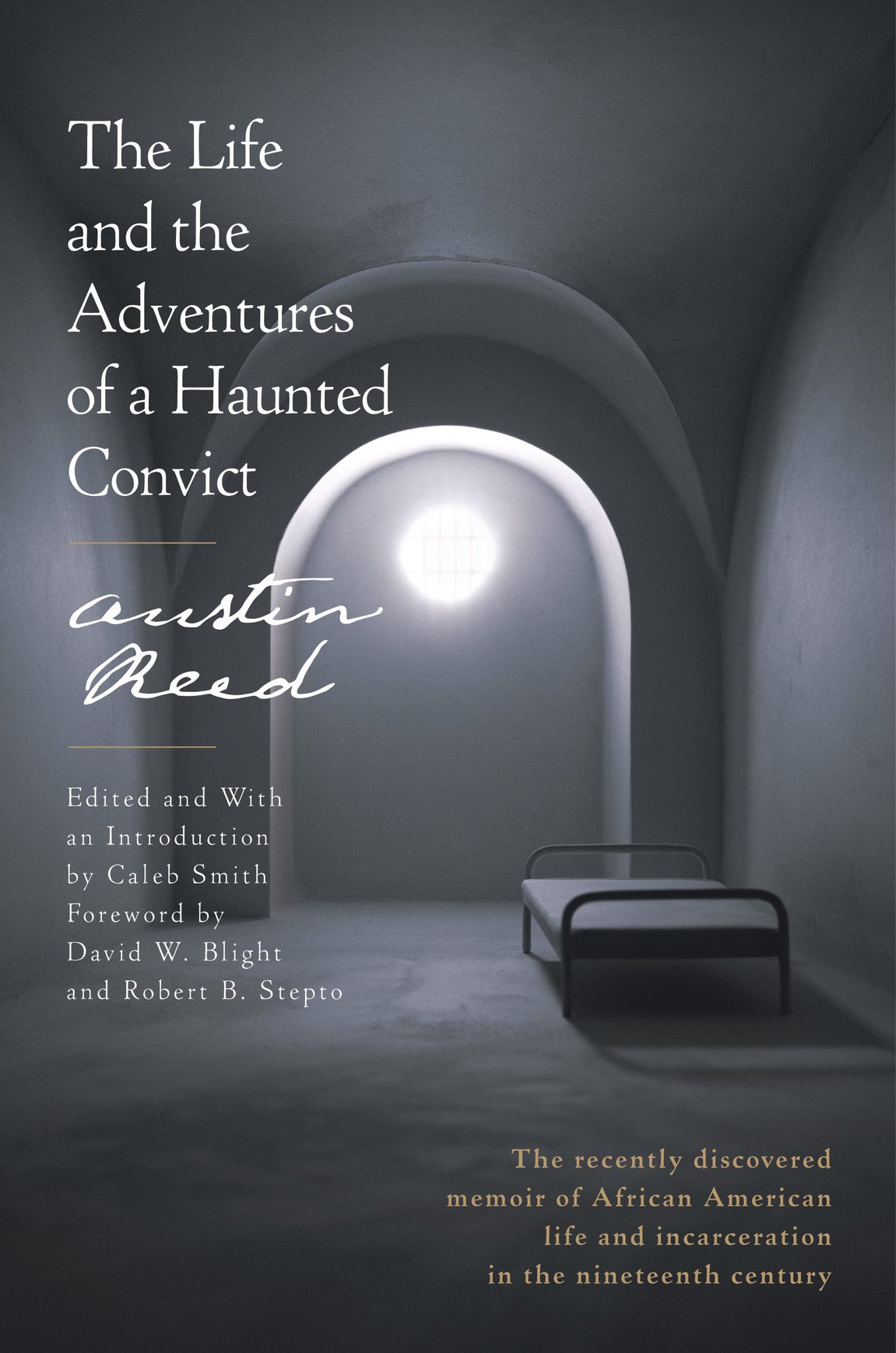

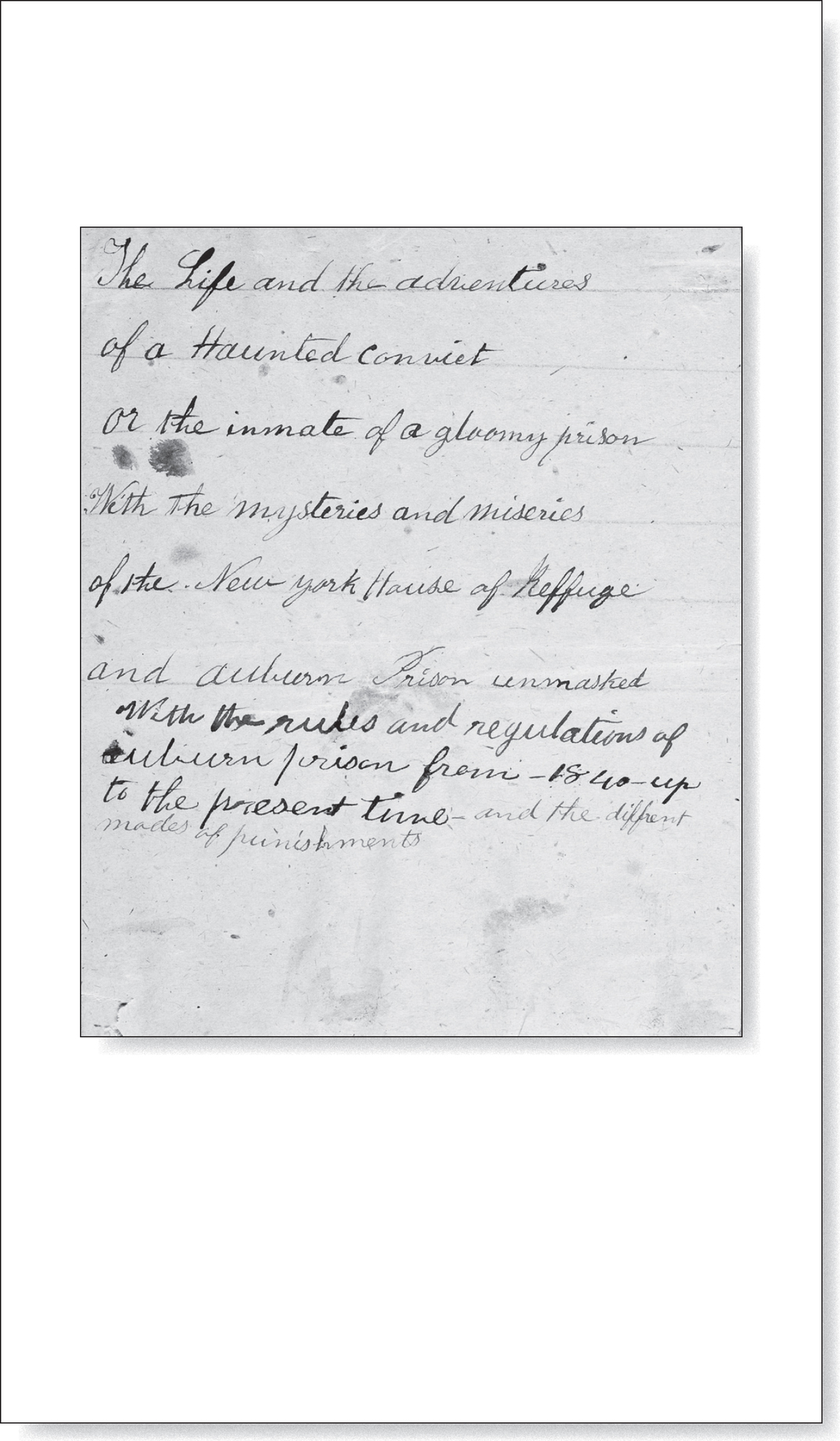

The life and the adventures of a haunted convict / by Austin Reed; edited by Caleb Smith; with a foreword by David W. Blight and Robert B. Stepto.

1. Reed, Austin, 1823? 2. African American prisonersNew York (State)Biography. 3. African AmericansBiography. 4. ReformatoriesNew York (State)History19th century. 5. PrisonsNew York (State)History19th century. 6. United StatesSocial conditions19th century. 7. United StatesRace relationsHistory19th century. I. Smith, Caleb, 1977 II. Title.

Foreword

by David W. Blight and Robert B. Stepto

R eading The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict today, in our era of mass incarceration and militarized policing, we immediately feel the force of Austin Reeds protest against the horrors of New Yorks House of Refuge and the Auburn State Prison. However, like the best of memoirs, this fascinating book has no one single task. Composed when the author was in his mid-thirties, it attempts to make sense of his life since his early childhood. Reed was not born into slavery, but as we get to know him in his pages we are well aware that he is a young African American, attempting to find his way in the antebellum United States. Like many of his contemporariesenslaved, fugitive, and freethe story Reed had to tell was one of harsh oppression and grinding exploitation. It was also the story of the development of his own mind. Carefully authenticated by Caleb Smith and a team of researchers from Yale University and elsewhere, Reeds book can now be placed in the great literary tradition that has rendered black life and experience from the first-person point of view. By 1858, when Reed concluded his account, the tradition already included a rich variety of slave narratives, poems, sermons, speeches, and works of fictionbut there was nothing quite like this sustained treatment of African American life inside the prison system that was just taking its modern shape.

As Reeds memoir circles back, again and again, to Rochester, New York, we are especially intrigued to consider him alongside another African American writer who has been central to our own scholarship on the tradition. Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in the South and, in time, took up residence in Reeds home city. In a trilogy of autobiographical works, Douglass offered some of the most memorable castigations of American slavery ever written. Such is the constitution of the human mind, he wrote in 1855, that when pressed to extremes, it often avails itself of the most opposite methods. Extremes meet in mind as in matter. Looking back on his experience as a slave child on a Maryland plantation, Douglass remembered a world of stark opposites, all but unalterable extremes he had to learn to navigate and survive. The plantation South of his childhood was a place of beauty and evil, of decadence and production, both his playground and his prison. (Douglasss rendering of slavery is full of prison metaphors.) As he became more aware of his predicament, he tried desperately to protect his body from destruction and to preserve his mind from disintegration.

Douglass famously told the story of his rise from bondage into freedom. Reeds story moves in the opposite direction, describing his fall from a tenuous liberty into the isolation and torment of incarceration. In this way, The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict provokes us to reconsider nineteenth-century African American literature and, indeed, the long arc of American history. Reading Austin Reed in the twenty-first century, we see how the formal abolition of Southern slavery may not have secured the liberty that Douglass risked everything to obtain for himself and many thousands more. Even before the Civil War, the free North was already building the penal system that now imprisons nearly a million African Americans. A century and a half after emancipation, one in three black men will spend time under confinement in Americas prisons and jails. Reed came of age inside some of the earliest institutions of penal captivity, and he had his own ideas about freedom, which seemed always to be receding beyond his grasp. In the meantime, he did his best to hold on to the elements of a lifephysical safety, a basic education, and a sense of belonging.

Two of Douglasss insights have special resonance as we study Reeds pages. First, thinking in part about his own childhood, Douglass declares that all slaves are orphans. Douglass never knew the true identity of his father, although it was likely one of his first two owners, and after the age of six he never again saw his mother, Harriet Bailey. Douglass spent much of his life trying to establish a durable identity and a sustainable set of relationships. Reeds history of incarceration, too, is a story about being orphaned from his home and his race. We note that Reed begins not at the House of Refuge but rather at the deathbed of his father, who is gasping his last breaths and giving his last fatherly advice. From this passage forward, the memoir tells of Reeds search for family. Revealingly, Reed almost always capitalizes the word Home.

Reed introduces us to a number of men who have been paternal figures or reminded him of his own father. One is Nathaniel Hart, or Mr. Heart, a superintendent of the House of Refuge, whose farewell address is praised by Reed because it offers the very parting words of my beloved father. Hart is replaced by Samuel S. Wood, who arranges for Reeds education in reading and writing. Later in the memoir, Reed recites a poem he learned thanks to Mr. Wood. Quite significantly, it is an antislavery poem. Mr. Wood, the man most responsible for Reeds literacy in his early years, is the abolitionist father figure in the memoir. At one point, Reed temporarily escapes from the reformatory, and he is taken into the home of a Mr. McCollough, the father of another Refuge boy. When the authorities come for Reed, McCollough confronts them. Reed is captured and reincarcerated in the end, but for an unforgettable moment McCollough becomes a protective father figure, a man standing up for Reed and against the reformatory.