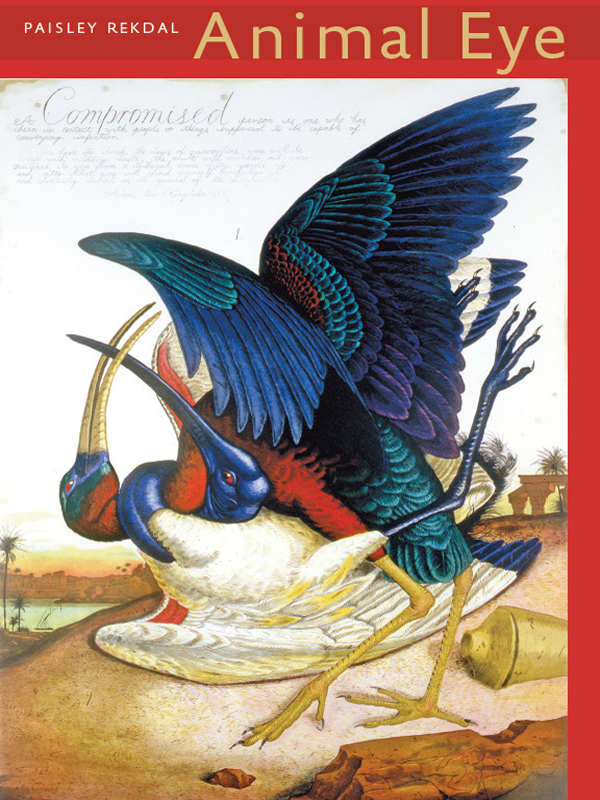

after Subhankar Banerjee The slides grow progressively red.

Arctic Scale

after Subhankar Banerjee The slides grow progressively red.

Now the black-and-yellow slicker encasing the man leans like a ballet dancer across the animal, matching its length and stretch, the strangely stiffened legs and slack head, the man's knife already deep inside the body. He slits fat down to membrane as muscle is exposed to air, the blue cells brightening, gleaming under plastic tendons the man massages then peels carefully away. There is no face. But children appear in the following frame, and now there is more red, the man and boys taking apart the thickened blood that foams, one enormous jelly pooling the snow so that rubber boots get wetted up to the calf and what they touch coats them utterly: there is no skin left, only hands becoming intimate with the work, cutting away horns and heart, tongue, lungs, kidney, liver, scooping out intestines filled with grass and placing them to the side, moving in to the custard-colored musk nodes bunched at the tail base, then further, looking for whatever is left of use: what beats and swells and stinks and pushes Now it's white across which ant-like bodies of pregnant caribou scatter in migration, photo shot from the belly of a Cessna. In the distance, mountain ranges and the unseen sea to which they travel, where the text below it announces oil rigs dip their certain needles and the Inuit women's breast milk has been declared hazardous waste. It is so beautiful here.

Here is a wall-sized field of green with patches of corn silk. Here is a miraculous range seamed with what I have to be told is coal, the enormous, glassy sea chattering its blue to the sky, the glacier clasped between them quietly disappearing. Here is a view too big to stand or even read the life inside: the slide clicks to an obscuring shore of gray beside which water churns with miniature baleens in knuckles of white. Changes again. Abstracted fields of snow and snow, and ice. In the last, the man has left a flap of caribou skin to dry.

It lies in a shrunken patch of snow, small as a child's pink mitten beside him; a valentine.

Ballard Locks

Air-struck, wound-gilled, ladder upon ladder of them thrashing through froth, herds of us climb the cement stair to watch this annual plunge back to dying, spawn; so much twisted light the whole tank seethes in a welter of bubbles: more like sequined purses than fish, champagned explosions beneath which the ever-moving smolt fume smacks against glass, churns them up to lake from sea level, the way, outside, fishing boats are dropped or raised in pressured chambers, hoses spraying the salt-slicked undersides a cleaner clean. Now the vessels can return to dock. Now the fish, in their similar chambers, rise and fall along the weirs, smelling the place instinct makes for them, city's pollutants sieved through grates: keeping fish where fish will spawn; changing the physics of it, changing ours as well: one giant world encased with plastic rock, seaweed transplanted in thick ribbons for schools to rest in before they work their way up the industrious journey: past shipyard, bus lot, train yard, past bear cave, past ice valley; past the place my father's father once, as a child, had stood with crowds and shot at them with guns then scooped them from the river with a net, such silvers, pinks crosshatched with black: now there's protective glass behind which gray shapes shift: change then change again. Can you see the jaws thickening with teeth, scales beginning to plush themselves with blood; can you see there is so little distinction here between beauty, violence, utility? The water looks like boiling sun.

Bang, the ladders say as they bring up fish into too-bright air, then down again, while the child watches the glass revolve its shapes into a hiss of light.

Bang, the boy repeats.

Bang, the boy repeats.

His finger points and points.

The Orchard

Even in the dream he's old, returning from his shed with a bucket of grubs he's picked off the roses. Dead already these twenty years, in my dream he moves steadily enough through the back field landscaped clear to the power lines that marched the length of Beacon Hill. My grandfather tended an apple orchard there, then set to making rows for sweet pea vines and tomatoes though his wife complained of this cultivated Eden, worrying it looked too country to the neighbors. In the winter my grandfather ordered seeds from a company out west, and all summer and partway through fall sprayed the fruit with a thick mist the catalogs recommended until, years later, hard, berry-sized tumors grew in his pancreas and his wife's small breasts. In the dream, he wears one of the thin T-shirts he favored, the raveled neck gone transparent at the seams, below this a familiar pair of faded slacks Mao-blue, my uncles ruefully called them bought in Beijing during the Reagan era.

He'd returned a final time to see his mother, and for gifts brought back Mao jackets and caps, Mao mailbags and figurines my uncles and mother promptly buried inside closets and dressers. On the fireplace, the last, framed photos of his mother before the children packed them off, the woman's shape spidery with age, slim feet bound in black. She died twice the summer he visited, the first after a stroke from which she revived a day later in the village's burial hut. My grandfather was good, I remember, at fixing bicycles and making shelves, he could replace a car clutch and once devoted an entire basement wall to a series of aquaria he'd built himself and stocked. None of these interests did he pass on to his children. He sat instead quietly through dinner, fingering his dish of salted plums, slipping each from its waxed wrapper to suck the meat to a pulp full of the brined, tart juice of summer.