ALSO BY DAVID ROBERTS

TRUE SUMMIT: What Really Happened on the Legendary Ascent of Annapurna

A NEWER WORLD: Kit Carson, John C. Frmont, and the Claiming of the American West

THE LOST EXPLORER: Finding Mallory on Mount Everest (with Conrad Anker)

ESCAPE ROUTES: Further Adventure Writings of David Roberts

IN SEARCH OF THE OLD ONES: Exploring the Anasazi World of the Southwest

ONCE THEY MOVED LIKE THE WIND: Cochise, Geronimo, and the Apache Wars

MOUNT MCKINLEY: The Conquest of Denali (with Bradford Washburn)

ICELAND: Land of the Sagas (with Jon Krakauer)

JEAN STAFFORD: A Biography

MOMENTS OF DOUBT: And Other Mountaineering Writings

GREAT EXPLORATION HOAXES DEBORAH: A Wilderness Narrative

THE MOUNTAIN OF MY FEAR

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2002 by David Roberts

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales: 1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

Designed by Karolina Harris

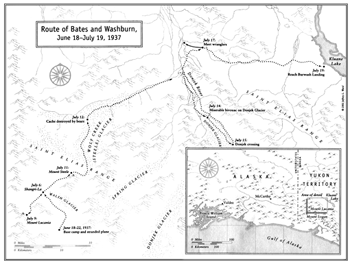

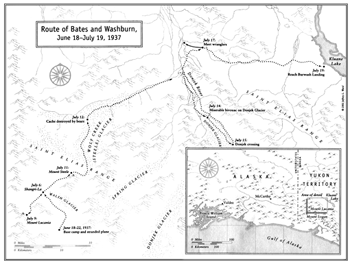

Map copyright Jeff Ward

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roberts, David, 1943

Escape from Lucania; an epic story of survival / David Roberts.

p. cm.

1. MountaineeringYukon TerritoryLucania, MountHistory. I. Title.

GV199.44.C22 Y848 2002

796.522097191dc21 2002073349

ISBN 0-7432-2432-9

eISBN-13: 978-0-743-23867-0

Credits: All photos by Bradford Washburn except as noted.

To Bob and BradStill fast and light in their nineties

CONTENTS

ESCAPE FROM LUCANIA

PROLOGUE

OPPOSITE me, upright in their adjoining armchairs, sat the two ninety-year-olds. Bald on top, with wisps of white hair crowning his ears, the aquiline nose and jutting chin proclaiming a lifetime of adamantine purpose, Henry Bradford Washburn, Jr., wore a brown dinner jacket over his red-plaid shirt, gray slacks, and canvas-and-rubber boots of the same make he had favored as a youth. His folded glasses were tucked into his shirt pocket. To Washburns right, his hairline checked in mid-recession, black strands still mingled with gray, the creases around his eyes etched deep in his round face, Robert Hicks Bates wore a green-checked jacket, threadbare gray sweater, and gray slacks that might have come from the same surplus store as his friends.

Both men looked frail, and both were a little hard of hearing. Approaching those armchairs, both men had walked with a slight stoop. Neither, I was sure, had gained a pound since his college days; perhaps they had each shrunk half an inch since their prime. The calm of a winters afternoon reigned in the living room of Batess second-floor apartment in this retirement community in Exeter, New Hampshire. A drab gray light flooded through south- and west-facing windows. Bobs wife of forty-seven years, Gail, served us tea and pound cake.

I watched the men talk as much as I listened to them. Brads forehead wrinkled as he stabbed the air with his right index finger to emphasize a point. Bob sat with his hands clasped like a preacher, his eyes squinting almost shut as he grinned in memory. Brads pronouncements came in cadenced, gravelly tones. Bob spoke in a soft, oddly high-pitched voice, delivering qualified comments on Brads categorical judgments. Everything about the pair bespoke the comfort in each others presence of two men who had been best friends for more than six decades.

As they chatted, I slipped into a reverie. Floating back sixty-four years in time, I saw Brad, at twenty-seven, lying head-to-toe with Bob, then twenty-six, as the pair shared a single sleeping bag in a wind-lashed tent at 14,000 feet in the heart of a glaciated wilderness in the Canadian Yukon. At that moment in 1937, there were no other human beings within eighty miles. A freak of nature had intersected with the mens intense ambition to land them here, on this high subarctic ridge where no one had ever been before, reduced to that cramped bivouac in a single bag. Most mountaineers, ensconced in such a predicament, would have dreaded the life-and-death struggle that was about to ensue. But in my minds eye, as they lay there cooking a dinner of Ovaltine, while the gale rattled the canvas that sheltered them from insupportable cold, both Brad and Bob had the blithe, insouciant look on their faces of pals sharing a fine adventure.

In that lonely camp, the men were five miles east of and 3,000 feet below the summit of Mount Lucania, one of the most remote peaks on the continent. In 1937, moreover, Lucania was the highest unclimbed mountain in North America. It had been attempted only once before, by a strong party in 1935 that, turning back from another summit ten miles away, had declared Lucania impregnable. That gauntlet thrown before their feet was the challenge that had brought Brad and Bob to the Yukon. Neither man, however, could have foreseen the insidious handicap with which fate would shackle them before allowing them to clutch at their prize.

During the 105 years since a team led by an Italian nobleman, the Duke of the Abruzzi, made the daring first ascent of 18,008-foot Mount Saint Elias, the fourth-highest peak in North America, there have been scores of truly extraordinary climbs pulled off in the wilds of Alaska and the Yukon. Because of its peculiar circumstances, however, the 1937 Lucania expedition remains unique. As I sat in Bob Batess living room, half-listening to the two old cronies reminisce, I mused that if I had to choose the single boldest deed in all that glorious history of northern ascent, I would vote for Bates and Washburns assault on Mount Lucania.

I had first met Brad thirty-nine years before, Bob a year or two after that. Both men had gone to Harvard in 1929, where they had met at the beginning of their sophomore year. At nineteen, Brad had under his belt a remarkable record as a teenage climber in the Alps; with a famous French guide, he had made a major first ascent on the Aiguille Verte above Chamonix. Bob, on the other hand, had done little more than hike in New Hampshires White Mountains before college.

At the time, the Harvard Mountaineering Club comprised the most ambitious collection of undergraduate mountaineers of any college or university in the country. Their specialty was remote, unclimbed peaks in Alaska and Canada. HMC climbers had done noteworthy things in the late 1920s, but it would be Bates and Washburns generationa small cadre of friends who pulled off first ascents in the great ranges all through the 30s and 40s and even into the 50sthat changed the face of American mountaineering.

When I went to Harvard myself in the fall of 1961, joining the HMC a few weeks after I arrived in Cambridge, the legacy of Bates and Washburns crowd hung over the club. As ambitious in our own way as they had been in the 1930s, we too turned our sights toward unclimbed routes in Alaska and Canada. Nor was the presence of the earlier generation merely a matter of disembodied legends looking sternly down upon us from the hallowed rafters of their achievements. A number of the renowned oldsters attended our meetings and served on the HMCs Advisory Council. Henry Hall, who had founded the club in the basement of his familys Coolidge Hill house in 1924, and who the next year had participated in the epochal first ascent of Mount Logan in the Yukon (the second-highest peak in North America), was unfailingly present at every meeting, piping up in his Boston Brahmin tones during slide shows to correct an undergraduates misidentification of some obscure peak in the Selkirk Range.