Table of Contents

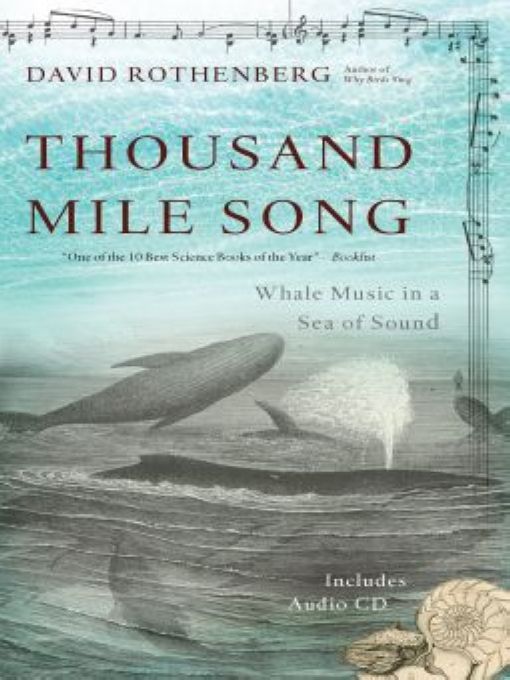

Praise forTHOUSAND MILE SONG

A warmly inquisitive writer who makes technical information as entertaining as tales about nude whale watchers, Rothenberg tells remarkably dramatic and funny stories of his musical encounters with whales.... As he rekindles whale awe, Rothenberg calls for a revitalized commitment to protecting these great singers of the sea.

Booklist (starred review)

This guy is capable of some mean jazz with whales. Yes, with whales.... The results are astounding.

New York Times

If you are musically inclined and interested in whales and whale song, this is the book for you. 11

Toronto Globe and Mail

Rothenbergs eloquent pen makes Thousand Mile Song a page-turner. The book is no less than a quest that sings because its stories hold such delightful tunes. Like the book, they resonate deeply well after we turn the final page.

Terrain.org

While Rothenbergs madcap mission to play jazz to the whales seems as crazy as Captain Ahabs demented hunt for the great White Whale, it is sometimes such obsessions that reveal inner truths. His affecting and often moving music is aural evidence of his attempt to bridge emotion and rationality, with a faintly bonkers but undoubtedly stimulating intent: to push at the barriers between human history and natural history. By coming to a better understanding of these strange, beautiful, and sentient animals, we begin to understand ourselves, too.

London Daily Telegraph

When it comes to the science of whale song, Rothenberg has done his homework. He has thoroughly researched the subject and presents his findings in clear, accessible prose.

Parabola

Rothenbergs jazz clarinet playing is really rather good. The whale samples add a spectral backdrop, sometimes forcing their way forwards, at other times remaining an echoey inspiration.

Financial Times

A joyful ride among the orcas, belugas and humpbacks, aimed at enticing these behemoths into a jam session... approaches the stirring border of interspecies contact with dignity and glee.

Kirkus

Have we found common ground? Or are we messing with their minds? Rothenberg, to his credit, doesnt give answers, but sends possibilities, like notes, floating out there. In our hearts, we should know that these wails are worth saving.

London Sunday Telegraph

Intriguing... [Rothenbergs] paean to the beautiful music these great mammals make should lend further support to attempts to save the whales at a time when they are increasingly threatened.

Publishers Weekly

The whales music is strange, stirring, soulful.

Chronicle of Higher Education

Is the artistic impulse solely human? Is making music with a giant underwater creature... perhaps a new way of understanding this mysterious and remarkable animal?

SHARMAN APT RUSSELL, OnEarth

Although Rothenberg is not the first musician to play along with whales, he may be the first to take the musical results seriously.

The Independent

Jamming with whales? A siren song from the deep....

Daily Mail (UK)

They say that there are two peaks of intelligence on this planet: humans and cetaceans. Im not sure about humans anymore, but this book identifies whales and dolphins as living in such a complex world of sound and song that they are certainly high on the ladder. Maybe at the top. I humbly bow to their superiority, and I applaud David Rothenberg for opening their world to us.

RICHARD ELLIS, author of Men and Whales

and The Empty Sea

Rothenbergs words and sounds reveal a fine and subtle music that crosses the boundary between land and sea.

JON HASSELL, musician and composer

Why do we feel differently about whales than about fish? Is it because they have the largest brains in the known universe? No; its because their songs touch the song centers in our own brains. Its not intellectualits soul. And its here.

CARL SAFINA, author of Song for the Blue Ocean

and Voyage of the Turtle

Also by David Rothenberg

Is It Painful to Think?

Hands End

Sudden Music

Blue Cliff Record

Always the Mountains

Why Birds Sing

chapter one

WE DIDNT KNOW, WE DIDNT KNOW

Whale Song Hits the Charts

EVERY MORNING PAUL KNAPP SETS OUT FROM THE SHORES OF Tortola in hopes of recording a humpback whale song better than the one he heard on Valentines Day, 1992.

I remember that day well, nods Paul, looking up at the sky. It was the fourteenth of February, and I was all alone. I went slowly and with respect, to the spot I always go to listen at the mouth of the bay. I didnt even see the whale. I think he was used to me by then and used to the sound of my engine. The whole moment made sense. Tall, tanned, in his mid-fifties, he looks like a man patient enough to spend years searching for the thing that matters most. Its never been quite like that again. But I keep coming backwaiting, listening.

Knapp spends the winter months camped out on the beach at Brewers Bay, an isolated cove in the Virgin Islands. The road to the place is still an improbable paved-over goat path. People here look pleased to have found a way to get away from it all. Some have come every winter for thirty years and say it hasnt changed a bit.

Paul stays here because of the whales, and the joy he finds in taking others out to hear their beautiful sounds. People sunning themselves on the beach get a surprise vacation treat when Knapp walks right up to them and says, Hey, wanna come out on my boat and hear some whale songs?

He pulls his tiny Caribe raft into the blue-green water from the perfect sandy arc of the beach and motors out to the mouth of the coveas far as he can go before the whitecaps get too rough for a rubber boat. He unpacks his equipment from a watertight box: an underwater microphone (known as a hydrophone), with a cable a hundred feet long. Paul drops this over the side of the boat only after tying it off to a guyline lest the thing disappear and coil swiftly down to the bottom. He plugs it into a little battery-powered boombox and gets ready to listen.

Sound underwater works in an entirely different way than above the surface. It travels about fifteen hundred meters per second, five times the speed it moves in air. Sounds travel much farther submerged than above the surface: the lower the pitch, the farther they go. There is also the constant background noise of waves, the din of endless shipping vessels from motorboats to tankers, and seismic rumblings from far inside the earth. But the loudest thing we hear today is shrimp.

The sound is surprisingly rough, windy, and crackly, making the tiny, rocking boat seem all the more fragile upon the moving swells. Were hearing snapping shrimp, nods Paul. Its a sound like electric sparks or radio interference from another star. He sits Buddha-like in big mirrored shades at the back by the motor, taking it all in. Some days youll hear nothing but the shrimp for hours. Waves drum against the rubber boat, and the hydrophone cable brushes against algae and rocks way down below.