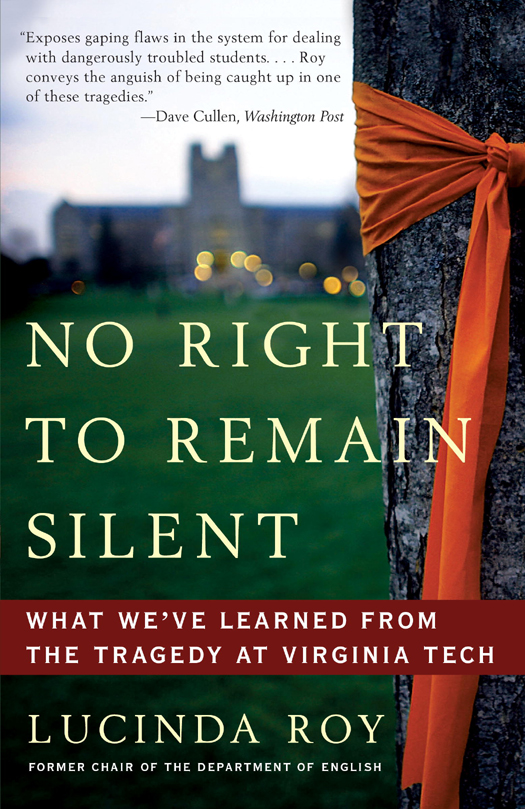

My thanks to CARE for helping me find ways to use funds from this book to assist families in Sierra Leone. My thanks also to educational and mental health nonprofit organizations in the United States for helping me find ways to support their endeavors.

My thanks to the faculty, staff, and students at Virginia Tech, who have been my friends and family for the past twenty-three years.

And thanks, as always, to Larry.

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can

and will be used against you

Prologue

O N THE morning of April 16, 2007, Seung-Hui Cho, wielding two semiautomatic handgunsa 9 mm Glock 19 and a .22-caliber Walther P22killed thirty-two students and faculty members at Virginia Tech. His first two victims were shot in West Ambler Johnston Residence Hall at approximately 7:15 A.M. The two bodies were discovered by the Virginia Tech Police Department roughly nine minutes later. In the interval between the double homicide and the attack on Norris Hall, Cho went back to his dorm room in Harper Residence Hall to change clothes. At 9:01 A.M. , from the downtown Blacksburg Post Office, he mailed a package to NBC and a letter to Virginia Techs Department of English. Between 9:15 and 9:30 A.M. , he chained shut three of the main doors to Norris Hall, attaching bomb threats to them. Cho then proceeded to the second floor where he opened fire. It was the second period of the day and classes had not been suspended, though an e-mail had been sent by the Virginia Tech administration at 9:26 A.M. notifying faculty, staff, and students that there had been a shooting in a dorm. The students who were killed or injured were in classes in Intermediate French, Elementary German, and Advanced Hydrology. A Solid Mechanics class, taught by seventy-six-year-old Holocaust survivor Professor Liviu Librescu, was also attacked, but most of the students escaped when Professor Librescu braced himself against the door and told students to jump out of the second-floor window. Students in a fifth class, Issues in Scientific Computing, successfully barricaded the door, preventing Cho from entering. In roughly eleven minutes, Cho fired approximately 174 rounds of ammunition, returning several times to classrooms he had already attacked. Courageous students and faculty did their best to escape from the barrage of bullets, some risking their own lives to try to save others, but Cho was determined to obliterate everyone he saw. During his murderous rampage in Norris Hall, student Seung-Hui Cho never uttered a word.

T HAT M ONDAY was one of the most bitterly cold and blustery April days we had seen in Blacksburg for some time. In the 2006-7 academic year, more than twenty-six thousand students had come to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (known simply as Virginia Tech) to learn. Surrounded by a breathtakingly beautiful 2,600-acre campus in rural southwestern Virginia, it seemed to be a place of abiding tranquillity. Students could learn and teachers could teach here in peace.

Eighteen months before the shootings, while serving as the chair of the English department at Virginia Tech, I worked one-on-one with Seung-Hui Cho after professor and poet Nikki Giovanni asked that he be removed from her class.), completed in August 2007 by a panel appointed by Governor Timothy M. Kaine, the response Seung-Hui Cho received was tragically inadequate. Even after he actively sought help, treatment was not administered by the Cook Counseling Center, nor did Cho receive follow-up treatment from on-campus or local counseling services following the order by a judge that he be treated on an outpatient basis. According to the Panel Report, there had been numerous red flags, but none of them had resulted in a comprehensive evaluation or a coordinated response.

In the wake of the tragedy, the response from faculty, staff, and alumni was remarkable. The town of Blacksburg embraced the university community and helped many of us get through some of the toughest times we have ever known. This was coupled with a tremendous outpouring of sympathy from around the world.

But unfortunately, this story is not simply one of heroism, endurance, and sympathy. It is more complicated and more human than that. It is about what preceded and what followed the tragedy as much as it is about the tragedy itself. It is the story of a university hampered both by its own labyrinthine bureaucracy and by the dogged determination of its administration to protect itself. It is about a system of public education in dire need of reformone which, in the case of Virginia Tech, resulted in conflicts of interest and a chronic inability to respond swiftly to crisis situations.

Seung-Hui Cho presents us with a series of difficult challenges. The sheer brutality of what occurred is overwhelming. This tragedy forces us to address some of the most pressing issues of our time: education, parenting, violence, youth subcultures, communication, censorship, mental health, gun control, and race. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the debate has often been explosive. The story, hard as it is to tell, is as relevant to kindergarten through twelfth grade (K-12) as it is to higher education. Teachers at every level and parents of children at every age face similar challenges.

It is vital when we look at a tragedy like this that we rid ourselves of our assumptions and biases before we try to come up with solutions. We need to ask what actually happened. What do we know about Cho and about the culture at Virginia Tech? What do other school shootings teach us about students? What can we learn from teachers, parents, and students themselves? Knee-jerk reactions are not helpful, and silence is less helpful still. We need to be open to the idea that contradiction may lie at the heart of this issue, and that any solutions which do not take this into account will fail.