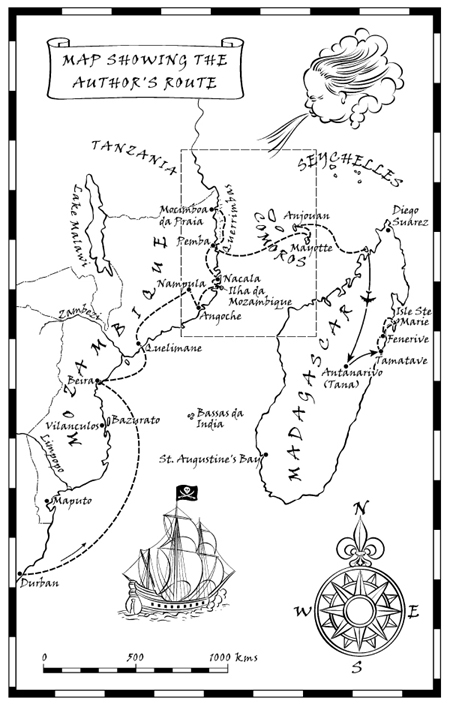

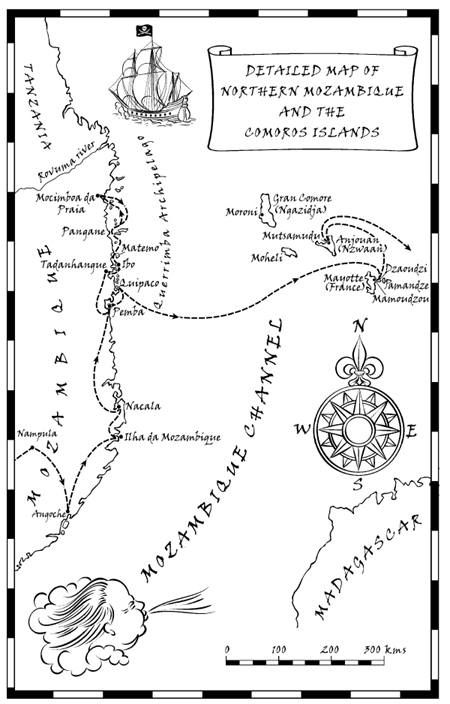

A great number of good people helped me along the way on this journey, some of them utopia-seekers themselves, one or two of them a little piratical as well. In South Africa I am grateful to Anton Rousseau in Capetown, Dick Dawson of the Durban Port Control, Ashley Dee and Glynn at Tallships, Joanne Rushby, Nisaar Mohamed and Theresa Kati. In Mozambique I was helped by Captain Jos Carvalho and his crew on the M.V. Songo, Gareth in Nacala, Charles Gornal-Jones and Vera Viegas in Pemba. On the island of Mayotte, Vincent Forest was the epitome of generosity as were Abdulkarim Abdallah and Ibrahim Djae on neighboring Anjouan. John Guthrie and Ernst Klaar told piratical stories with all the elan of men who know the Indian Ocean intimately. Others who gave invaluable assistance with the text or translations were Tamara Castro, Jan Abegglen, Eduardo Latorre, Mike Pedley, Maggie Body, and Sophie Carr. I am also grateful to Carolyn Whitaker, Judith Rushby, and to my editor at Constable, Carol OBrien. A few others I have left out because they prefer anonymity and a few names have been changed in the text for the same reason; to the others who I may have forgotten or whose names I never knew, I apologise for their absence here.

Chasing the Mountain of Light:

Across India on the Trail of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

Children of Kali:

Through India in Search of Bandits,

the Thug Cult, and the British Raj

Eating the Flowers of Paradise:

A Journey through the Drug Fields of Ethiopia and Yemen

HUNTING PIRATE HEAVEN

In Search of Lost Pirate Utopias

KEVIN RUSHBY

I am a free Prince, and I have as much Authority to wage War on the whole World, as he who has a hundred Sail of Ships at Sea, and an Army of 100,000 Men in the Field There is no arguing with such snivelling Puppies, who allow Superiors to kick them about Deck at Pleasure; and pin their Faith upon a Pimp of a Parson; a Squab, who neither practises nor believes what he puts upon the chuckle-headed Fools he preaches to.

The pirate leader, Captain Bellamy, quoted in

Captain Johnsons History of the Pyrates

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and seeing a better country, sets sail.

Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man under Socialism in the

Fortnightly Review, February 1891

Contents

1

Introduction Cape Canaveral, AD 1601

We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

I first caught sight of him on the swing bridge at Deptford: a victim of piracy, as he later described himself, though perhaps witness would be a better word. He was wearing an old-fashioned macintosh with the collar turned up and a tweed cap pulled low against the rain. When I came alongside and stopped to look down at the creek towards the Thames, he glanced at me and I noted the long patrician nose and rather pale brown skin. There was a moment when we might have spoken then, but I was trying to balance my umbrella against the wind and at the same time see what lay below in the water. I had come down here filled with enthusiasm for all things maritime and historical: the year 2001 would mark the four hundredth anniversary of the first East India Company voyage and I was in search of the very spot where they departed. I was far too busy with my mission to register the fact that he was Indian.

The creek draws a grubby but definite borderline between the packaged heritage and cosy polished pubs of Greenwich and the very different world of Deptford. It wriggles down to the Thames through banks of wooden pilings, a few traffic cones sticking out of the grey slime like abandoned party hats. Other waterways of London have been lost inside concrete pipes or new channels, but the creek harks back to an older, less controlled, landscape: its sinuous curves and stinking mud banks carry the whiff of raw nature, if not raw sewage.

I did not linger: cars were sending clouds of fine spray across the pavement and on the far side of the bridge was a large puddle where the Indian gentleman narrowly avoided a soaking from a bus. I watched him turn right towards the river, then followed.

All around Deptford there are tiny clues to its historic past: the mulberry tree in Sayes Court garden, its gnarled trunk so aged that it lies like a giant spider on its back; the corbled doorways in Alberry Street with carvings reminiscent of ships figureheads, and the skull-and-crossbone gateposts at St Nicholass Church, said to be the inspiration for the Jolly Roger.

Inside the church the Jacobean pulpit is held aloft by a ships figurehead and the walls hold tributes to the shipwrights and captains who prayed in the pews. This is a Deptford church, no soaring neo-classical lines of a Wren or Hawksmoor as you would expect to find in Greenwich, but a mongrel of brick and stone, a patched-up survivor with a charnel house in its grimy graveyard and a plaque on the wall for Christopher Marlowe, stabbed to death in a nearby bawdy house in 1593.

Then, as now, Deptford was a place for people with journeys in their boots and mysteries in mind: a rich source of material for Marlowe who had opened up the English horizons with his Tamburlaine and Dr Faustus. Like his contemporary, Shakespeare, he was fascinated by the discoveries of the New World and Old, the tales brought back by the sailors and merchants who thronged the ale-houses. It was a time when the known world was expanding at dizzying speed: every returning ship seemed to bring back fresh and ever more bizarre curiosities, and every departure was packed with ever more ambitious dreamers.

The streets now, by comparison, are deserted. If the children of the poor immigrant families play outside, they stay close to the front door. Further along I found a battered car crouched in the gutter, its bodywork patched and uneven, the back seat a mess of baby clothes, blankets and baggage. Behind it a woman was holding a toddler out over the gutter, her back hunched against the rain. She glanced up, aggressively, then turned away. Deptford was a place to start journeys, I thought, and a place to leave.

I followed the street round: on one side some dismal flats, on the other derelict riverside industrial plots. I wanted to get down to the water and after a short distance I found what I was searching for: a cobbled alleyway leading between high brick walls. It ended at an open barred gate beyond which I could see the great grey Thames sliding past. Steps led down through a deep gulch of green weedy walls to a strip of mud with a curious patch of yellow sand. That surprised me: a warm yellow strip worthy of some far-off and sunnier climate. There were no boats to be seen, no newsprint carriers unloading at Convoy Wharf next door, built on top of Henry VIIIs shipyard and now the furthest point to which large vessels penetrate the Thames. There was not even a water taxi or a barge, only the shipwrecked shopping trolleys which, I suppose, is all you need to load up with the spices of the east these days. There was certainly nothing to mark the most historic stretch of river in the world, the place where Drake tied up after his circumnavigation and Elizabeth came to dub him, the place where Martin Frobisher set out for the North-West Passage, and the place where so many India-bound ships, including the first voyage, were prepared.