VANCOUVER HARBOUR

Watercolour and ink by Bruno Bobak

welcome home, quince

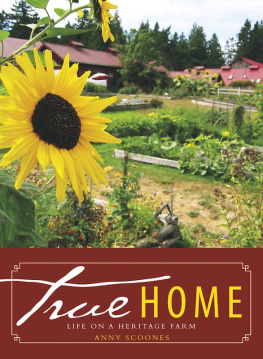

In 1900, Glamorgan Farm consisted of hundreds of acres spreading out in the form of meadows rolling westward toward Patricia (or Pat, as we say) Bay. Richard John, a Welshman from Glamorganshire, brought his family here in 1870 and built an elegant family home where the peeling yellow grandstand of the Sandown Racetrack now sits. The blackberries are enveloping the building, as racing has all but ended, and the property is slowly reverting back to the earth. The original driveway to the John house was off the Trans-Canada Highway, also known as the Pat Bay Highway, which, in 1900, was a dirt lane.

In 1900, Glamorgan Farm consisted of hundreds of acres spreading out in the form of meadows rolling westward toward Patricia (or Pat, as we say) Bay. Richard John, a Welshman from Glamorganshire, brought his family here in 1870 and built an elegant family home where the peeling yellow grandstand of the Sandown Racetrack now sits. The blackberries are enveloping the building, as racing has all but ended, and the property is slowly reverting back to the earth. The original driveway to the John house was off the Trans-Canada Highway, also known as the Pat Bay Highway, which, in 1900, was a dirt lane.

The highway runs from the ferry terminal (which takes you to Vancouver and the mainland) to Victoria; on the east side of it is the seaside town of Sidney. The highway is often heavy with traffic: transport trucks and tour buses speed under the turquoise overpasses and past cement barricades, turn-off lanes, and green exit signs.

Off in a little rural area west of all this activity, on a country lane lined with hawthorn and honeysuckle hedgerows, on a hill across the road from crumbling Sandown, is Glamorgan Farm, eight acres of the original hundreds, its eleven log structures still standing (with their new red tin roofs) up a poplar-lined driveway.

The dogs and I often walk through the overgrown meadow behind the track where the grass is up to my waist and I need to carry clippers to make my way through the tangled hawthorn. Theres an old millpond, and a daffodil wood within what looks like an ancient orchard of apples, plums, pears, and some towering cherries. Rusting back to the minerals in the earth, under the thickets of rose hips and Indian plum, is an old blue Austin; only its windows and its rotting, ripped vinyl seat resist Mother Natures hold, although she has the last laugh by producing a few violet crocuses every spring that push through the decomposing rubber tires. The faded paint on the rounded fenders has become a home to colourful orange lichen.

My friend Freda is a keen local historian who volunteers at the Sidney museum. On Heritage Day, a municipal celebration of local history that we hosted on Glamorgan Farm, Freda and her husband, Ken, supplied all sorts of antique hand ploughs, butter churns, and farm implements. One day Freda brought me a folder of historic articles about Glamorgan Farm, copied from original photos and old newspaper columns she had found at the Sidney archives.

I read through them slowly every evening by the fire, and I came across a yellowed scrap describing a big quince bush that had been planted in 1900 at the entrance to the John farm. I deduced that this would be out toward the highway at the end of Glamorgan Road where the Sidney Chamber of Commerce has its tourist information centre, beside the RV sales centres and under the pedestrian overpass.

I rarely use that way to come home from Sidney, preferring to come down Glamorgan Road from the back way, off Mills Road and past the Legion up by the airport, so I had never paid much attention to the vegetation and landscape at the end of Sandown near the highway, except to notice at times when I rode Valnah, my Russian horse, down to the Sandown field where people dump old couches and household garbage in the hedgerow.

When I discovered from Fredas article that the old quince might still be growing down in that area somewhere, I got on my bike on a rainy day and ventured over Sandowns potholed gravel lane toward the turquoise overpass. Someone had declared I love Amanda in black spray paint on the tourist centre.

Between the tourist centre and the gritty, wet highway, there was indeed a scrubby-looking clump of unkempt shrubbery: sprawling junipers, entangling blackberries and hawthorn, and some unrecognizable greenery with sweet-smelling white flowers. The traffic was speeding by in the drizzle that day, sending grime and exhaust splashing over the cement barriers where I was standing. The thicket of brush was too dense to identify, but within the thriving jungle I could see a shrub with tender little leaves, striving to grasp some light, entwined by a massive vine in aggressive competition.

The following day I took clippers with me and cut through the thorns, brambles, and invasive graspers that were holding tight to the thick bush in the centre. When I reached it, I saw some pale pink spring buds on one spindly branch. It was indeed the old quince!

I spoke to Jack, our municipal engineer, who looked it up on North Saanichs inventory of the highway construction that had taken place over the years and, sure enough, he confirmed that the quince was there, and worse yet, he said, All that brush has to be removedits preventing a good sight line for vehicles. I had an idea.

I rushed down to the municipal hall to Brian, North Saanichs superintendent of parks and everything outdoors, as he puts it. Brian is a big man who wears plaid shirts and has lived in North Saanich all his life. He knows everyone, all the old-timers as well as the First Nations people. He remembers the old community hall, the original schoolhouse, and the old gas station in Deep Cove. His children babysit for Fredas grandchildren and raise rabbits to exhibit at the Saanichton Fair, and they regularly visit Glamorgan Farm with buckets of windfall apples for the pigs. Hes a good friend and the easiest person to talk to about ideas for North Saanich, and hes kind to animals.

One time when he was in charge of chipping an enormous load of storm debris in the municipal yard, he delayed the work because a local family of quail had set up house in the brush and were preparing to hatch their young. The family is now a familiar sight on Glamorgan Road, darting in and out of the hedgerows, and Brian finally chipped the debris, which was then put back on the forest floor in our municipal parks.

So Brian was the perfect person to talk to about my idea of removing the old quince and transplanting it to the entrance of what is now Glamorgan Farm. No problem, he said cheerily. We can do that, and Cliff can prune it back. Weve got some bone meal in the shed.

I remember having a surge of love for North Saanich, this little rural municipality where they care enough to save an old quince and a family of quail. Brian and his assistant, Cliff, came over later in the day and chose a spot on the boulevard by the white-railed fence and hedgerow.

Later in the week, a few men from the municipal yard came over with shovels. Wearing grey wool undershirts, jeans with red suspenders, and neon work vests, they dug an enormous hole (seemingly effortlessly) on the chosen site. It was a typical grey day, the air saturated with drizzle. Cliff sprinkled the bone meal in the rich black soil and soon the yellow, mud-splattered backhoe came rumbling over the hill, its oversized rubber tires bouncing the dear old quince bush in its bucket. They had done itthe quince had come home!

They gently placed the huge bush in the hole, and Cliff, as if the quince was his injured child, made sure that its roots sat in the most comfortable position, that the bush was upright, and that the soil was gently shovelled back in to stabilize it. He then snipped off a few damaged branches and we raked decomposed leaves around the base and hosed off the mud on the young shoots. Welcome home, quince, I said, and the work crew went off to their next job, repairing the storm-battered walking path along Pat Bay.

Cliff and Brian came by every so often to check on the quince (and for muffins). In early spring the bush burst forth in a mass of pink and red blossoms. That summer, everyone was talking about global warming, and there were two days in July that were unbearably hot. It was more than forty degrees, so scorching that I kept all the animals inside the cool barns. Many plants in the hedgerow were burnt, including the poor quince, whose little green leaves dried to a crisp. I kept the hose running in the night into the roots and hosed off the tinder-dry stems at dawn before the heat returned. Come autumn, the quince recovered and, with its will to live, sprouted a fresh supply of leaves and, lo and behold, produced three hard, shrivelled quinces on its thick, thorny limbs.

In 1900, Glamorgan Farm consisted of hundreds of acres spreading out in the form of meadows rolling westward toward Patricia (or Pat, as we say) Bay. Richard John, a Welshman from Glamorganshire, brought his family here in 1870 and built an elegant family home where the peeling yellow grandstand of the Sandown Racetrack now sits. The blackberries are enveloping the building, as racing has all but ended, and the property is slowly reverting back to the earth. The original driveway to the John house was off the Trans-Canada Highway, also known as the Pat Bay Highway, which, in 1900, was a dirt lane.

In 1900, Glamorgan Farm consisted of hundreds of acres spreading out in the form of meadows rolling westward toward Patricia (or Pat, as we say) Bay. Richard John, a Welshman from Glamorganshire, brought his family here in 1870 and built an elegant family home where the peeling yellow grandstand of the Sandown Racetrack now sits. The blackberries are enveloping the building, as racing has all but ended, and the property is slowly reverting back to the earth. The original driveway to the John house was off the Trans-Canada Highway, also known as the Pat Bay Highway, which, in 1900, was a dirt lane.