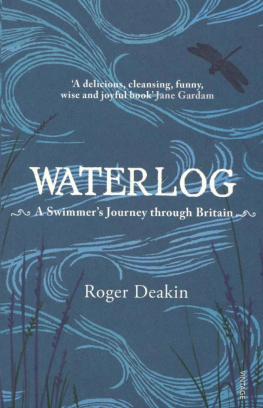

Roger Deakin was unique; he saw and felt the world like nobody else. Notes from Walnut Tree Farm is as remarkable and as affecting as anything John Muir wrote; in fact, I think it is this centurys Walden. It might even be the best of his books; or perhaps there is no need to rank them like this. It completes the triptych, begun with Waterlog and Wildwood, in the most wonderful way.

A delicious, cleansing, funny, wise and joyful book, so wonderfully full of energy and life. I love it Jane Gardam

A triumph of topographical and naturalist writing to weave environmental and cultural concerns so deftly together in this enchanting and original travel book is a real achievement Independent

Enchanting, very funny, every page carries a fascinating nugget. Should serve to make us appreciate more keenly all that we have here on earth one of the greatest of all Nature writers Mail on Sunday

Roger Deakin, who died in August 2006, shortly after completing the manuscript for Wildwood, was a writer, broadcaster and film-maker with a particular interest in nature and the environment. He lived for many years in Suffolk, where he swam regularly in his moat at Walnut Tree Farm, in the River Waveney and in the sea, in between travelling widely through the landscapes he writes about in his books, Waterlog and Wildwood, both of which have been acclaimed as classics of nature writing.

Notes from

Walnut Tree Farm

ROGER DEAKIN

Edited by Alison Hastie and Terence Blacker

HAMISH HAMILTON

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

HAMISH HAMILTON

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2008

1

Text copyright Estate of Roger Deakin, 2008

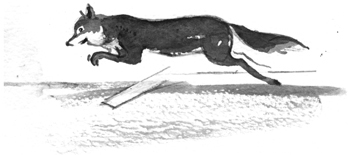

Illustrations copyright David Holmes, 2008

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above,

no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced

into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise),

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner

and the above publisher of this book

978-0-14-190025-4

Foreword

For the last six years of his life, Roger Deakin kept a record of his daily life, work, thoughts and memories. Forty-five lined exercise books were completed in his distinctive, bold handwriting. Each was numbered and paginated, with a table of contents carefully listed on the cover.

The entries themselves were altogether freer. Spontaneous, playful, impassioned and sometimes experimental, they were Rogers everyday observations, and releected the events of his inner and outer life as they happened.

Some of the entries were research notes for Wildwood, the book he was writing at the time, or for one of his radio programmes, while others were written during his travels in Australia or Eastern Europe. Most of the contents, though, related to his life at Walnut Tree Farm, the extraordinary, much loved house in Suffolk where he lived for the last thirty years of his life. It is these entries which have provided the material for this book.

We have selected extracts from the notebooks, including dates when they were mentioned, and have arranged them month by month to form one composite year. Abbreviations have been expanded, but otherwise Rogers words have been allowed to speak for themselves.

Alison Hastie

Terence Blacker

July 2008

January

1st January

I am lying full length on my belly on frozen snow and frosty tussocks in the railway wood blowing like a dragon into the wigwam of a fire at the core of a tangled blackthorn bonfire. I am clearing the blackthorn suckers that march out from the hedge like the army in Macbeth, the marching wood, threatening to overwhelm the whole wood in their dense, spiny thicket.

The technique is to get right down on the ground and go in with the triangular bow-saw at ground level, then grab the cut stems and drag the bushes away to the bonfire, which grows like a giant porcupine, bristling with spines that inleict a particular, unforgettable ache in the hands and thumbs of the woodman.

The bonfire just keeps working itself up to a sudden burst of wildly crackling, spitting leame, and burning a chimney up its centre. Then it dies down, frosting the twigs with fire but failing to ignite with any conviction because the wood is too fresh, too green and sappy. It is exhausting work, crawling at rabbit level through a blackthorn thicket and sawing through the tough little trunks. You realize why blackthorn was used defensively as a dead hedge by the Saxons; it is the true precursor of barbed wire.

I stumble back up the field for a tea-break to listen to myself on Home Planet on the radio and fall headlong in the snow by the shepherds hut. Tracks everywhere in the snow, mostly rabbit, and a single bee orchid standing up with dried seeds in the snowy field.

A mauve, misty penumbra across the fields under a duck-egg sky and the glow of sunset. Everything very still and quiet.

2nd January

Another brilliant, intensely cold morning. Trees and everything enamelled and frosted, sparkling and frilly with frost.

Hard to get the car started cold diesel and frozen windscreens. Put more antifreeze in the tractor. Then a snow drive over icy roads to see Ronnie Blythe at Bottengoms.

We have lunch in the Six Bells in Bures cod and chips, and halves of Guinness and set off to Ager Fen, where we walk through the ancient mixed woods of cherry, oak, fir, hazel, willow, poplar, ash. Ronnie says all country children were conceived in woods, because you couldnt make love in the house: there were too many people in there children, parents, etc., no privacy at all. So you went to the woods.