Table of Contents

For E.F.O.

INTRODUCTION

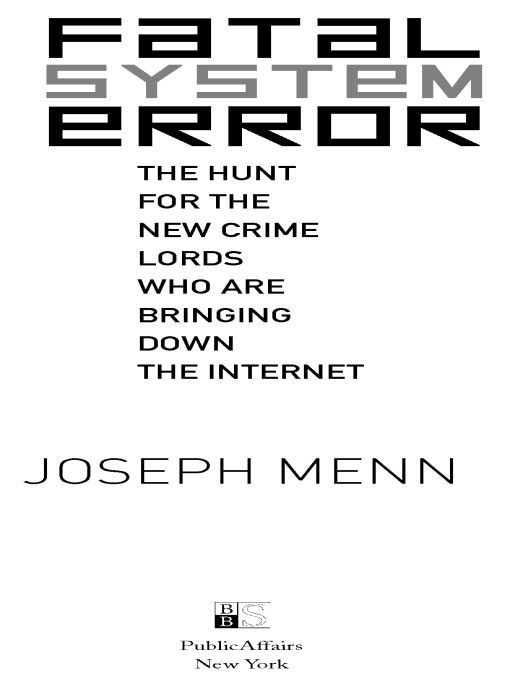

WHEN I FIRST MET BARRETT LYON in 2004, I was covering Internet security for the Los AngelesTimes from an office in San Francisco. His story was so goodand met a journalistic need so deepthat I had a hard time believing it was true.

For more than a year, I had been grappling with an onslaught of urgent but complicated stories. Seemingly every week brought a new computer virus that shot around the world. Many had real impact, shutting down large company networks or overstuffing mailboxes with spam until they started rejecting legitimate messages. Even so, the problems could be hard to explain before the deadline for the next days newspaperespecially if the viruses took advantage of obscure software holes in ways researchers were still struggling to understand.

It wasnt just that the technical explications were tricky. There were few heroes, except for a handful of almost unquotably nerdy researchers. The villains were usually shadows. When someone did get caught in those days, it was typically a maladjusted teenager.

Yet something important was happening. As the world connected to more computers and depended on them for more things, the bad guys were wreaking havoc. Worse, the viruses unleashed for mischiefs sake were getting supplanted by those that were about making money.

Then came a new series of Internet attacks, much easier to understand technologically, that illustrated the new thuggery in bold strokes. Assailants unknown simply overwhelmed business websites with so much bogus traffic that the sites failed. To stop, they wanted $30,000 or more wired to countries in Eastern Europe.

I called around to the victimized companies, looking in part for something to make the tale even better, so that any reader could follow along and learn. I quickly heard about cyber defender Barrett Lyon.

He was young and unassuming, yet enormously bright and articulate. He had actually chatted with the attackers. Yes, he knew some of their names. He didnt happen to have a record of those chats, did he? Sure he did. Dont suppose the cops had taken much interest in the case, since they normally throw up their hands at cybercrime? Why, yes, they hadthe FBI, the Secret Service, and the national authorities in the U.K. and Russia. The saga grew until it gave a panoramic view of organized crimes brazen new initiative.

Of course, the sort of attack that Barrett specialized in warding off was merely one dramatic aspect of a bigger and rapidly metastasizing problemtechnology advances that were helping criminals even more than they were helping consumers. Online scams and identity theft soared, and an entire underground industry grew. Enormous data heists from such places as the information broker ChoicePoint and retailer T.J. Maxx generated plenty of headlines.

By 2009, 30 percent of Americans had become identity theft victims, companies and individuals were losing an estimated $1 trillion a year to Internet criminals, and confidence in the electronic economy and the stability of the information infrastructure was fraying. Now it wasnt only about cash, but about international politics and cyberwarfare as well.

Even if someone were dedicated to sorting out what was going on and where it was leading, there wasnt much help to be found. Few with any knowledge had an incentive to talk. Not Microsoft or the other software companies, whose flawed products made penetration by criminals so easy; not most security firms, whose services were falling farther behind; and not law enforcement agencies, which were catching less than 1 percent of the bad guys.

Private researchers could explain how one virus differed from previous versions, law enforcement could complain about how the trails from identity theft crimes went overseas and grew cold, and a handful of academics could hold forth on the politics of Eastern Europe. But even as fears rose to the point that President Barack Obama devoted a speech to the vast dangers of cybercrime, cyberspying, and cyberwar, almost no one could give a full picture.

Once more, Barrett Lyon could. By then, I learned, he had penetrated not just the Russian mob but the American mob as well, and had gone undercover again, this time wearing a wire for the FBI. Only now does that work become public.

In turn, he and I also met British agent Andy Crocker, who followed his leads and plunged deeper than any previous Westerner into hacking in the former Soviet Unionand whose adventures have never been recounted. Together we retraced the greatest international cybercrime prosecution in history, as an officer from the Russian MVD put it to us in a vodka toast.

Their combined stories shine by far the brightest light yet into a shadow economy that is worth several times more than the illegal drug trade, that has already disrupted national governments, and that has the potential to undermine Western affluence and security. This book is about the triumph of two men who went where none like them had gone before.

But it is also a warning about disaster well along in the making. By mid-2009, word had spread far enough in secretive government circles about the exploits of Barrett Lyon and Andy Crocker that they were flown to Washington to lecture more than a hundred top spies for the U.S. and its allies. Yet those officials still werent getting the most important message. And both heroes had quit working for their governments.

Cybercrime is too important to be left to the professionals. Read this book and understand why.

PART ONE

WARGAMES

FLYING DOWN TO COSTA RICA, Barrett Lyon couldnt wait to meet his new clients in the flesh. It was two days after Christmas 2003, and the twenty-five-year-old computer whiz from near Californias Lake Tahoe figured to be welcomed like a conquering hero. The early-morning flight banked away from San Francisco International Airport, piercing the winter clouds as it gained altitude. Barrett looked over at the pretty brunette by his side and felt he was on the cusp of a new and better phase in his life. BetCRISshort for Bet Costa Rica International Sportswas not only treating him to the trip, it was paying for his girlfriend, Rachelle Sterling, to come along. It was their first plane journey together, and her first outside the country. He hoped it would go a long way toward easing the tensions of the past six weeks.

Barrett now realized he must have seemed irrationally obsessed with BetCRIS, defending an unseen company in Costa Rica against invisible enemies in yet another country. Most of the time all Rachelle saw was Barretts six-foot, two-inch frame hunched over the boomerang-shaped desk in their cramped Sacramento condo. For twenty or more hours a day Barrett stared blearily into the computer screens he used to track electronic assaults. He even blew off the family Thanksgiving he had promised her so he could try to get his programs and configurations working better. He had been too focused to thank her for bringing him the leftover turkey, let alone to explain everything he was doing.

To Barrett it was a battle for the ages, one that reminded him of WarGames, the 1983 movie memorialized in the poster on his wall. In the film, a bright but unschooled teen looking to play games online stumbles into a government supercomputer, nearly launching World War III. Barrett thought he had skipped the initial blunder and gone straight to the fun stuff, trying to short-circuit a cyberbattle that was costing real people their jobs and fortunes.