The Secret Life of

Ealing Studios

Contents

Guide

I would like to thank the following Ealing veterans for their memories of working at the studio, without whom this book would not have been possible.

Christopher Barry (assistant director)

Lord Michael Birkett (personal assistant to Michael Balcon/assistant director)

Betty Collins (personal assistant to Alexander MacKendrick)

Ray Cooney (child actor)

Peggy Cummins (actress)

Norman Dorme (art department)

Alex Douet (camera assistant)

Rex Hipple (sound department)

Maureen Jympson (administration/casting department)

Mandy Miller (actress)

Peter Musgrave (sound department)

Madge Nettleton (production secretary/continuity)

Gerry OHara (assistant director)

Joan Parcell (production secretary)

Nicholas Parsons (actor)

David Peers (assistant director/production manager)

Tom Priestley (editorial department)

Tony Rimmington (art department)

Maurice Selwyn (runner/clapper loader)

Ronnie Taylor (camera operator)

David Tringham (assistant director)

Ken Westbury (camera department)

Robert Winter (editorial department)

Also many thanks to Joanna McCallum for sharing her memories of her parents, Googie Withers and John McCallum, and to Sylvan Mason for allowing extracts from her father Jack Whittinghams film diary. And special thanks to Charles Barr and James McCabe.

What an amazing story. A group of talented people come together under a charismatic leader, they band together to meet the demands of a special set of circumstances, and they create something beautiful and lasting. And then, as the circumstances change, they drift apart, everything comes to an end the way things do. And it lives, powerfully, in their combined memories.

When I was young and getting interested in movies watching them, slowly figuring out that they were made, then that they were made by teams of individuals, and then, gradually, how they were made there were names that meant something. Sometimes they were the names of people directors, producers, actors. Sometimes they were the names of companies, each of which had its own special logo: the Warner Brothers shield, the Universal planet, RKOs radio tower, Powell and Pressburgers The Archers with the arrow hitting the target, the strong man striking the J. Arthur Rank gong. And then there was Ealing Studios, a modest design: the company name between laurel branches, like parentheses.

We associated each of these logos with a certain mood or feeling, comprised of the memories of all the pictures youd seen from that company coming together in the mind. With the Ealing pictures, we always anticipated something special. There were all of those wonderful British actors, familiar friends who were right there when you needed them, and I always loved seeing the new faces, the people whod been welcomed into the fold. And every Ealing film seemed to have been hand-made each element, from the narrative to the production design to the cinematography to the acting to the language to the tone. Thats very important the tone of the Ealing movies was quite different from everything else around, the comedies in particular of course.

As we learn in this lovingly compiled history, Ealings glory years, from Michael Balcons arrival in the late 30s through to the sale of the studio facilities to the BBC in the mid-50s, coincided with the War followed by the long national recovery. You see this again and again in film history, people drawn together at a time of national emergency, working together to create films that responded to the moment, sometimes directly (as in the case of Next of Kin or Went the Day Well?) and sometimes indirectly, striking a chord with the audience (Im thinking of Dead of Night or Robert Hamers It Always Rains on Sunday or the comedies directed by Alexander Mackendrick and Charles Crichton). A little world was created at Ealing, a world that was sometimes egalitarian and sometimes not, every day filled with triumphs and calamities and sudden promotions and hilarious misadventures. When things were at their best, everyone was working towards the common goal of making a great movie.

How did a movie like Kind Hearts and Coronets, one of the peaks of English moviemaking, actually come to be made? A brilliant director (Hamer), equally brilliant actors (Alec Guinness, Dennis Price, Valerie Hobson, Hugh Griffith), a great writer (John Dighton) and DP (Douglas Slocombe, who never looked at a light meter he read the sunlight on his hand), Art Director (William Kellner) and Costume Designer (Anthony Mendleson) but beyond that you have to think about the conditions that made it all possible, the tone that Balcon set. And you could say the same of Dead of Night or Whiskey Galore or The Lavender Hill Mob or smaller, lesser-known films like Champagne Charlie or Secret People.

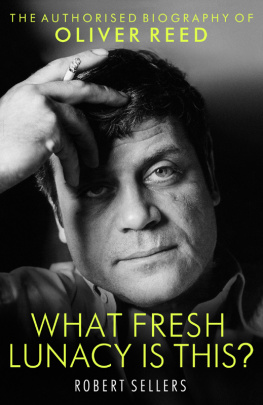

I love the reminiscences that Robert Sellers has compiled, about the can-do-spirit, the near-disasters (like Hamer and his crew forgetting that theyd left Alec Guinness strapped in an underwater cage for five minutes), the petty grievances of the union leaders (which Peter Sellers studied and later made use of in Im Alright Jack), the challenging working conditions in the studio itself. It all feels oddly familiar. In fact, this lively, funny, moving history of a movie studio and the people who made it feels uncannily likean Ealing comedy.

Martin Scorsese, 2015

The first thing that struck you upon arriving at Ealing Studios was that it didnt look like a film studio at all. It also had absolutely no right being where it was, slap bang in the middle of suburbia, surrounded on either side by prosperous homes and set on a village green, an odd place for a thriving hubbub of movie-making. But there it was, its glorious white administrative block that faced out onto the road and first greeted the gaze of the visitor, looking for all the world like a small private Regency manor house.

The next thing that caught your eye was a large man dressed in a smart uniform, usually standing to attention. His name was Robin Adair and he was an ex Coldstream Guards sergeant and guarded the front gate as if it were the Khyber Pass. He was quite a formidable character, recalls Maurice Selwyn, who started as a runner at the studio. And his word was absolutely law. Nobody got in without his permission. He was a permanent fixture at the studio, standing by the gates in all weathers from first thing in the morning until the end of the working day, always on hand to greet the artists arriving in their cars and studio head Michael Balcon in his chauffeur-driven limousine.

Moving on past the gate, one came to the inner workings, the coalface as it were. And yet, what lay before you was scarcely sprawling, not in the same league as Shepperton, Pinewood or even Denham. Ealing was close knit, compact, with everything bunched together. As one visiting journalist amusingly noted, Ealing was, A postage stamp of a studio, with a back lot barely large enough to turn a car in.