J. Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson

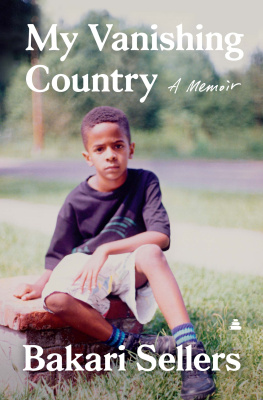

I m from whats called the Low Country in South Carolina, where beauty and blight and history are intertwined. You can drive for fifty miles in any direction and still be on the same grounds where slaves, some of them my not-so-distant ancestors, toiled over cotton, indigo, sugarcane, rice, wheatgrass, and soybeans. Particularly, my hometown is Denmark, South Carolinaa place where everybody knew my last name, a name, I would learn as a child, that was colored with honor and infamy.

To get to Denmark, which is in Bamberg County, just drive down Highway 321 if youre coming from Columbia, the state capital. Youll pass fields of corn and cotton and flash by acres of swampland creeping over neon-green beds of marsh.

Youll eventually seem to arrive halfway around the globe in a little slice of Scandinavia, where towns dubbed Norway, Sweden, and finally Denmark appear one after another. The first two are so teeny, youll miss them if you blink. Before them, youll tick past a chicken farm that always smells of pure shit before you eventually get to Denmark, a community of thirty-four hundred souls, nearly all African American.

Visitors often think that the Scandinavian towns, which are nine miles apart from each other, are so called because of Nordic settlers, but thats not so. The monikers actually followed that theme only when my hometown was named after B. A. Denmark, a nineteenth-century railroad businessman.

I always liked to imagine my own alternative theory: that my town was tagged after a badass freed and literate African-American carpenter named Denmark Vesey, who was convicted and executed for leading the rising, a deftly plotted slave revolt in 1822. Veseys sense of justice and his rebellious nature have always appealed to me.

Continuing through those isolated hamlets, youll pass graceful Victorians and dilapidated shotgun houses. They say a bullet can fly from the front door straight through the back door of these narrow dwellings, which is how we once believed the shotguns got their names. But a growing theory is that the name of these skinny homes, which are no more than twelve feet wide, comes from a style of house in West Africa called shogun, which means Gods house. The shotguns play a huge role in southern history and African-American folklore in the deep parts of the South, as do the abandoned buildings that make up the dying downtowns.

To me, theres a rustic beauty to ghost towns, with their ramshackle clues of a fruitful past. The empty downtowns conjure feelings of nostalgia and sorrow simultaneously: in Denmark, I can drive up to a gas station and see a man from childhood standing outside, and I realize that same man has been standing around there for twenty-some years.

Denmark is an intriguing country town, especially when you consider what it has to offer, or all it used to be. Its about an hour from Augusta, Charleston, and Columbia, and thanks to old B. A., it was once a transportation hub, with trains from three large train companies coming and going. Once bustling, Denmarks downtown today is the perfect example of whats happening in the forgotten rural Black Belt, a term once used to label a section of the country known for its dark, rich soil. Now, however, it describes a chain of connecting states known as the nations largest contiguous thread of poverty.

Most of the businesses that were open in Denmark in my fathers day are now shuttered. A Laundromat is still open, as well as Pooles Five and Dime, a few restaurants, and a hardware storebut thats nearly it. The entire area no longer has a hospital. Whether its Denmark or somewhere else in Alabama or Mississippi, if you had driven through forty years ago, it would have been pulsing with energy and black life. The train tracks traveled north, south, east, and west, heading to Chicago, Atlanta, New York City, and Los Angeles. At one time, Denmark had a pickle factory, a Coca-Cola bottling plant, and a furniture manufacturing company. The town was packed with people of all tradesbricklayers, technicians, construction workers, bakers, painters, and cooksas well as black businesses of every kind, which is why you had some wealth in a place thats 85 percent black.

Despite todays extreme poverty in my hometown, significant numbers of educated black people have always lived in Denmark, especially since two historically black colleges are located there: Denmark Technical College and Voorhees College, where my father was president. All these things were going for it, but when the tracks got pulled up, politics blew in. People talk about corporations coming in and destroying towns, but I believe that South Carolina was devastated by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The textile mills started closing their doors and moving overseas, people started leaving, and with them, all the jobs vanished.

* * *

In 1990, when I was six years old, my father moved our family from Greensboro, North Carolina, back to his hometown of Denmark, from which he had fled more than twenty years earlier. He was the citys prodigal son coming home. If I had been older, our move to this black, rural outpost would have given me pause, but the very thing I should have been wary about is the thing my six-year-old self loved most: everybody knew our name.

In South Carolina, black folk dont ask each others last name; we ask about kin. And, of course, there are many versions of this custom, depending on where youre from. For instance, African Americans in the states Upcountry might say, Whats your peoples name? In Denmark, its Whos your people? Its a very direct question to determine whos someones mother and father and any other relative one might need to know. It helps us to determine whether were blood and possibly even more. It reveals our lineage and background.

The custom can easily be traced back to slavery. Slaves were separated from their loved ones and stripped of everything they held dear. So now, were left always searching for a kindred spirit, grasping for home, which is why we call each other cousin or uncle or aunt or sis, even when were not blood-related.

As a reluctant little boy moving to a new town, I quickly realized Denmark wasnt unfamiliar territory. Everywhere I turned, someone, child or adult, was telling me, Were your kin, or You Bakari... Cleveland Sellers boy!, or You Little CL, or I knew your granddaddy!

Denmark was where my roots were planted.

Its home.

* * *

Driving through Denmarks desolate downtown is like looking into a loved ones eyes and no longer seeing a twinkle. The light has dimmed. What once was a sparkle, is no longer.

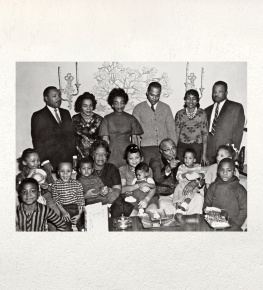

Denmark is a microcosm of the forgotten black South, where isolation, lack of economic development, and substandard housing and school systems have devastated it to its core. What Ive seen all my life in Denmark helped me to cultivate my political belief that small businesses are the lifeblood of all communities. Whether you look back at Tulsas wealthy Black Wall Street of the early twentieth century or the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s or the Sellers family in Denmark circa 1950s and 1960s, black people and black power always meant being able to have economic self-sustainability and access to the ballot box.

However, you can see in poor black towns today that international industry and a globalized economy have left most of us behind. Denmark is now a place where no one can take for granted things such as clean water, a simple Wi-Fi connection, and a local hospital.