Also by Ronald Schwartz

Latin American Films, 19321994: A Critical Filmography (McFarland, 1997; paperback 2005)

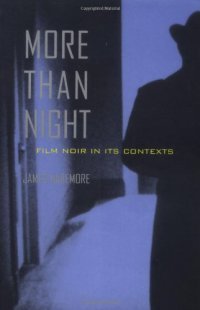

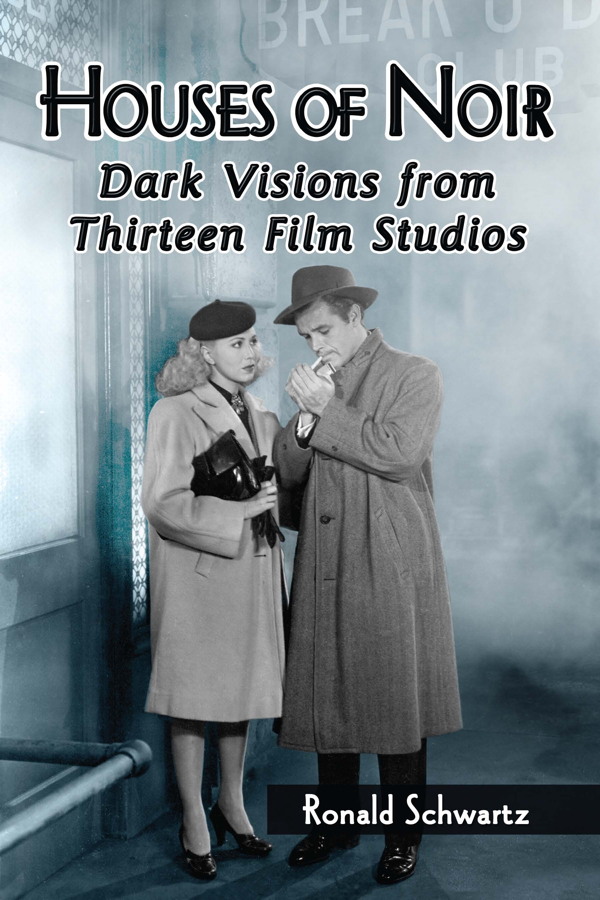

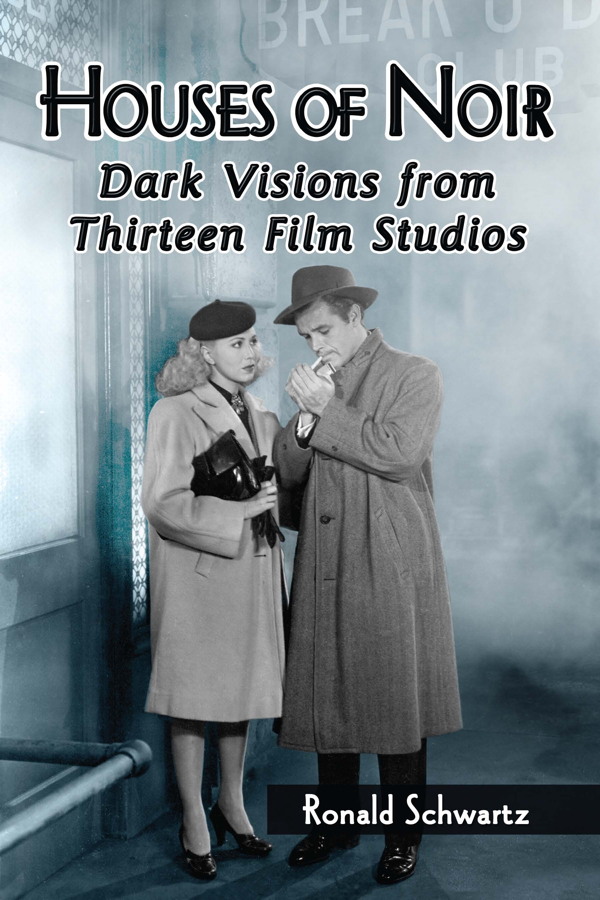

Houses of Noir

Dark Visions from Thirteen Film Studios

Ronald Schwartz

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0460-2

2014 Ronald Schwartz. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Claudia Drake and Tom Neal in Detour, 1945 (Producers Releasing Corporation/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For my wonderful wife Amelia,

our son Jonathan and

Charles Mitchell, who also loved to sit

in the dark and watch films noirs...

Acknowledgments

I must thank my circle of friends who are enamored of the crime film, especially film noir. If it was not for their inspiration, I would never have embarked on writing a third volume on the subject. Friends like Ray Meola, Jeff Leibowitz and the Mandelbaum brothers, Howard and Ronald of Photofest, have been particularly encouraging.

Also, I thank my editors at McFarlanda very professional staff who had faith that I could bring this original work to fruition.

Special thanks go to Christianne and Jazz van de Lima in our co-op as well as to Ken Eisner. I am grateful for the encouragement of my childhood friend Dr. Allen Richman of Stephen F. Austin State University and his wife Joan. And on a personal note, I would like to thank Dr. Benjamin Zaremski and Dr. Gary Giangola of Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, who saved my life.

Preface

The crime film always interested me for as long as I can remember. I used to escape to the movies as early as five years old and even played truant from school just so I could see a double feature at the local Surf Theatre in Coney Island in 1942. But the Technicolor pirate and adventure and musical films didnt interest me as much as the black and white crime dramas with those intricate plots. I remember watching Double Indemnity for the first time in 1944 or 1945 and was so impressed by its actors, plot, music and photography that I went to see it twice!

The same thing happened when I watched Lana Turner and John Garfield in The Postman Always Rings Twice. The actors absolutely sizzled on the screen. I was a bit too young to know about sex and murder, but I knew that crime never paid and no one got away with his or her chicanery. That was back in 1946, when a French writer called these films noirblack, or dark.

I became such a film addict that my parents had to drag me home from the local theater to have supper on time and prepare for school the next day. But my real education took place in the local cinemas, watching those wonderful crime films by Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak and Jules Dassin. I was hooked on noir and, decades later, decided to write a few books about it.

Now it is 2013 and I am still as excited as that five-year-old child back in the forties, always anxious to see revivals of the great old films. It is still the films of the forties and fifties I find the most fascinating. In my introduction I will concisely identify what film noir is and discuss why each major, minor and independent studio during the period from 1940 to 1958 chose to produce this type of film.

Introduction

What is film noir?

Film noir is a style that predates the 1940s and continues into the twenty-first century. Noir is a French word meaning black, and although film noir literally means black film, it refers to the mood of many black-and-white American films made between 1940 and 1960 in which a male protagonist is usually led to his destruction by a femme fatale and winds up getting neither the money nor the dame.

It is a gloomy style of American film identified by the French film critics. Nino Frank coined the term film noir in 1946 and the French authors Raymond Borde and Etinne Chaumenton, in their seminal critical work Panorama du film noir amricain (19411953), used noir to define a particular sort of American cinema just before World War II until the late 1950s even though the roots of film noir can be seen as early as silent days.

It has its silent stylistic predecessors in films by D.W. Griffith (Musketeers of Pig Alley) and Raoul Walsh (Regeneration), its pre-noir tendencies in the 20s and 30s films of Josef von Sternberg (Underworld) and Fritz Lang (M), before it finally emerged as a style in Boris Ingsters Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), Orson Welles Citizen Kane (1941) and John Hustons The Maltese Falcon (1941).

The popularity of film noir reached its zenith during World War II with films such as Billy Wilders Double Indemnity, Howard Hawks The Big Sleep and Tay Garnetts The Postman Always Rings Twice. If one could imagine oneself in Paris in 1945, watching these and The Maltese Falcon and Murder, My Sweet, and other noir films of that era, one would get a very negative view of America, a sexually debased, perverse and amoral society.

The French saw this type of movie as part of American cinemas New Wave. These crime films had their antecedents in the French Poetic Realism of the 30s (the films of Jean Gabin, for example) and in German Expressionism of the 20s and 30s. The European influences of cinema impressed many Hollywood directors.

The French public was no longer interested in the artful but predictable Hollywood musicals but the gutsy mysterious film noirs where a femme fatale (fatal woman) can seduce a dull or dumb lover into killing her husband or other lovers, his first step on the road to ruin.

There were also hommes fatales (fatal men) who seduced women into labyrinthine schemes but they usually met their end in lethal shoot-outs or unpredictable events like car accidents.

Film noir uses low-key lighting, highly angled camera set-ups and dark music to tell its stories. Shot mostly in black and white, the cycle of noir films ends in 1958 with either Odds Against Tomorrow or Touch of Evil. It must be said that no American director during that period ever used the word noir, nor did he or she set out to create a style or genre. It was the French critics who applied the word noir to this group of films that shared a similar photographic, artistic and thematic style. Therefore, noir is not a genre, but an unconscious stylistic movement shared by many directors in 1940s and 1950s Hollywood.

It is also certain that societal influences contributed to the design of these particular films. Their thematic pessimism can be attributed to the postWorld War II disillusionment of returning servicemen on a variety of issues, such as their replacement by women in the workforce and the difficulty they had adjusting to postwar values. Coincidentally, there was a rise in acceptance of the hard-boiled school of writers, whose escapist, masculine themes provided entertainment during the war years. The novels of James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, David Goodis, Dashiell Hammett and Cornell Woolrich were widely read and provided the raw material for film noirs. Also, because of the use of new high-speed film stock and the ease of photographing outside of the studio (on location), real people and streets were used in a great number of films of the period. And, finally, many migrs from France and Germany, who filmed in Hollywood and on location, brought with them a style of expressionist cinema that developed in Europe in the early 1930s and reached its fulfillment in the film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s.

Next page