Table of Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

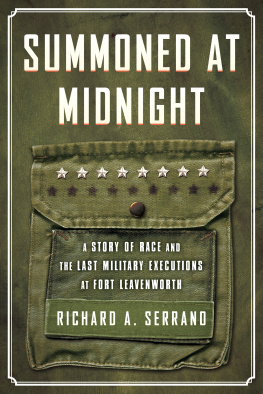

ALSO BY RICHARD A. SERRANO

One of Ours: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing

My Grandfathers Prison: A Story of Death and Deceit in 1940s Kansas City

Last of the Blue and Gray: Old Men, Stolen Glory, and the Mystery That Outlived the Civil War

American Endurance: Buffalo Bill, the Great Cowboy Race of 1893, and the Vanishing Wild West

Fr Elise

Many of my friends fled into the service, all to be changed there, and rarely for the better, many to be ruined, and many to die.

JAMES BALDWIN , The Fire Next Time

The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.

W. E. B. DU BOIS , The Souls of Black Folk

PROLOGUE

In the last half of the 1950s, all eight of the white soldiers on the armys death row at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, were spared. Their crimes were heinous, unthinkable, and little disputed. Rape, murder, the worst of the worst. Yet the white inmates served only a few years on death row and eventually were paroled and returned home.

During this same period, the army hanged only black soldierseight men in all. Their crimes were no less shocking than the white soldiers. But the stark disparity in the mens outcomes reflected the nations troubled road toward integration in the US military and the racial dynamics of the country leading into the civil rights era. It also drew sharp political attention.

Then, in the first weeks of the new Kennedy administration, in 1961, the fate of yet another condemned soldier, the last man on death row at the time, came up for reconsideration. He was a black army private from the Old south, younger than all the rest of the doomed men and just as guilty. Suddenly, debate over his fate became a fulcrum on which the past nearly six decades have pivoted. Would he be spared or, like his fellow black soldiers, summoned at midnight to the army gallows?

Chapter One

ARMY JUSTICE

Snow was coming, and another cold front was settling in. American soldiers at Camp Roeder in the eastern Alps were already shivering in their army outpost in Occupied Austria. The rifles, tanks, and mortars of World War II had gone silent for ten years, but the Allied forces still patrolled the rugged German border. Now, on this first day of winter, December 1954, ice and snowflakes whitened a small stream outside Salzburg. The creek would freeze overnight. Christmas was just a few days away.

Private First Class John Arthur Bennett, a handsome man with deep-set, dark brown eyes, had been posted there only a short while, part of a US Army headquarters battery. He served as an ammunition handler and drove an army truck around the sprawling American compound. The young man had recently won a National Defense Service Medal and a Sharpshooter Badge. He also had taken survival training.

Though he was far from home, the army seemed a good fit for the eighteen-year-old soldier. He worked hard, drew excellent performance ratings, and like any smart soldier, kept his head down. His commanding officer liked hima lot. The army promised him a future. That is why he enlisted. His brothers had joined up, too; one was promoted to sergeant major while serving in Europe and the Far East.

Each morning brought Bennett steady work, a paycheck, and a path out of the poverty and segregation of his hometown in southern Virginia. But Bennett was a black soldier in a still largely white mans army, and before the sun came up after that December 21 snowfall, he stood arrested for sexually assaulting a white Austrian girl and leaving her for dead in a snow-dusted brook. The US Army charged him with rape and attempted murder. Her belongings were recovered near the creek, and Bennett, exhausted and frightened under questioning by military police, signed what army officers and military prosecutors called a confession.

Local authorities insisted that Bennett be handed over to Austrian authorities; they had no death penalty, and their maximum punishment for rape was twenty years. But the army instead court-martialed Bennett, in what his defense and appellate lawyers derided as a show trial to ease the anger of local Austrians after a decade of Allied occupation. An all-white jury of two army colonels, four lieutenant colonels, two majors, and a captain deliberated for twenty-five minutes and sentenced him to death by hanging. Bennett was placed in chains and leg irons; shipped to a brig in Mannheim, Germany, then a holding cell in Pennsylvania; and finally to the armys notorious death row deep inside the Castle, formally known as the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

The armys death row was dug into a partial basement below the Castle walls. For six years, Bennett was housed in a solitary cell along a steel-andiron tier called Seven Base. Most of the other condemned soldiers were already there when Bennett arrived, and they soon adopted him as the youngest among them sentenced to die.

Unlike all the rest, he was not a murderer. Others had shot fellow soldiers to death, even army officers. Some had slain civilians, and several had murdered children, including the young daughter of an army colonel. In the years between Bennetts military trial and when he finally left death row, he watched as the lives of all eight of the condemned white soldiers, most from middle-class homes in the North, were spared. Not only were their sentences commuted, but all eventually were paroled and set free.

The army hanged only black soldiers in those half-dozen yearseight in allsummoned at midnight to the gallows. The army chose that 12 a.m. hour because it saw no reason to wait for any last-minute reprieves as a doomed mans last day wore on. And at midnight, it hoped, the others on death row would be sleeping and the rest of the prison silent.

Like Bennett, these eight black prisoners were products of a harsh American South, born into poverty and raised under Jim Crow, trying to fit into an army that had been ordered to desegregate. Each died without money or means.

One black army private from Tennessee, Louis M. Suttles, was executed for killing a taxi driver in Missouri. Shortly after his arrest, he was taken into a small room packed with men brandishing firearms and a woman drawing her finger across her throat. An army investigator scanned the crowd and warned Suttles, How would you like to have about ten of those fellows get hold of you? Married with two young daughters, he insisted army police had scared him into confessing. But Suttless case drew few supporters and certainly no Washington insiders or high-priced attorneys.

Six weeks before his hanging, Suttless mother, Mrs. Gentry Collier of Chattanooga, wrote the Eisenhower White House, her handwriting neat though she was partly illiterate. I am begger for his life, she pleaded. I am the only one he got to look to he dont have a father he Die when Louis was small I am cripple. She added, [H]e was a good boy both white and colored love him he ant never have ben in trouble tell he was in the army.

All on death row, white and black, clearly recognized that in the late 1950s, none were treated alike. There were no written Jim Crow rules on the armys death row. White military guards served them all the same meals, offered them the same books and magazines, and sent them to the same showers and the recreation yard. But everyone realized that a completely different and dual system permeated beyond those basement walls. Attorneys trained in capital litigation represented white soldiers waiting to be hanged. Sympathetic editorial write-ups lobbied to save their lives. Often the public rallied around them, too, launching letter-writing and fund-raising campaigns and other petition drives. In the end, high-ranking army officers, military judges, and Washington power brokers in the Eisenhower administration and on Capitol Hill helped save their lives. The white soldiers had far less to fear.